When I first moved to New York in the late 90s, print still dominated the art world and digital was barely in sight. Mailing a physical exhibition announcement (usually with Modern Postcard or a similar company) was de rigueur. And so were business cards: as I started attending dinners and openings, I was struck by how seemingly everyone (artists, curators, arts writers, and more) had business cards at the ready to exchange with one another. I did not have any, so I would have to awkwardly write my phone and email on a piece of paper, which made me feel quite unprofessional.

Those early card-less experiences made me realize something about artists and business (or calling) cards, which might be even more interesting to think now that these objects are rapidly falling into disuse.

In The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman likens the process of introducing ourselves to others as the exchange of a “basic social coin”, with “awe on one side and shame on the other. The audience senses secret mysteries and powers behind the performance, and the performer senses that his chief secrets are petty ones.” Inasmuch as artists used business or calling cards, they often became the means by which an acquaintance would be given the right degree of access to take a peek, paraphrasing Goffman, into the “secret mysteries and powers” of the artist.

This is because, in spite of their small size, business/calling cards lay exactly at the intersection of the artist’s identity and sense of purpose. They are a means not only to connect with someone, either informally or professionally, but they are also a small representation of the artist as a person. Because of that, artists often paid attention to the shape and form of this kind of representation and sometimes (especially after the 1960s) embrace it as an extension of their artistic practice, be it as a sample of what they do or as a conceptual project onto itself.

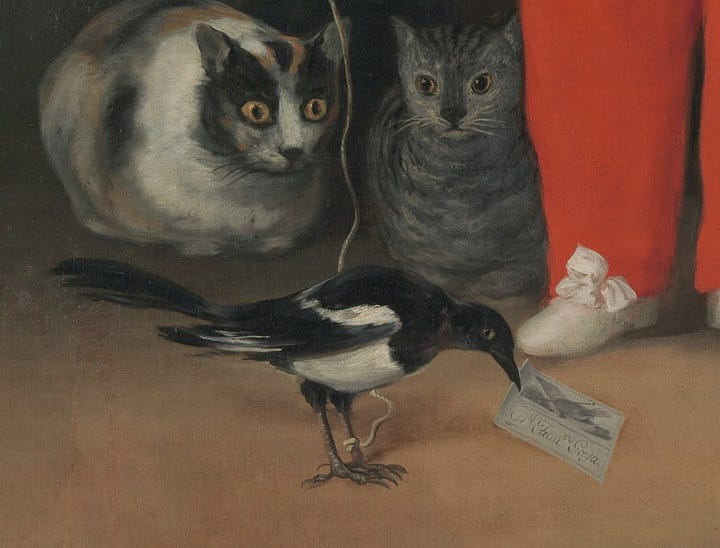

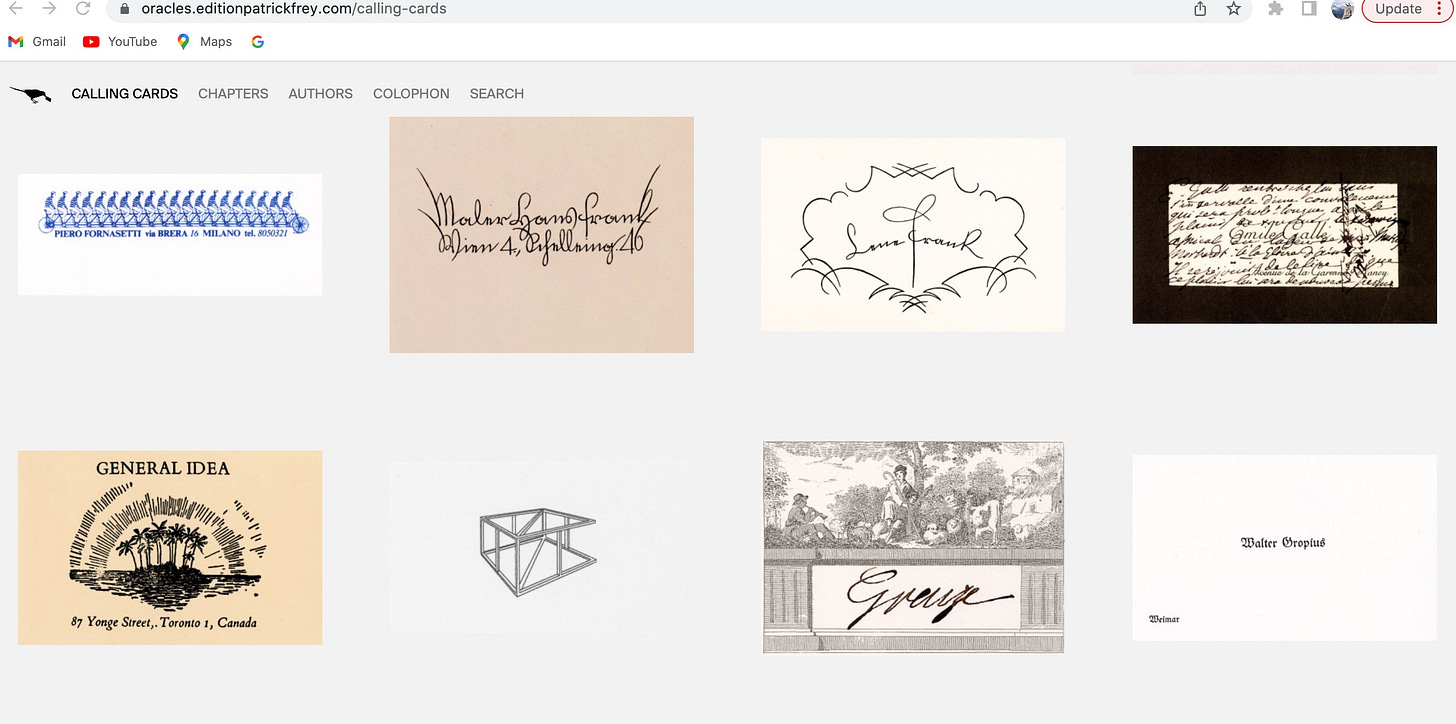

The first modern example of such self-referential use might be found in Goya’s portrait of Don Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga from 1787, a portrait of the son of the counts of Altamira where the artist depicts a pet magpie holding a calling card with the artist’s name, which doubles as the signature of the work. The reference is highlighted in the book Oracles—Artists Calling Cards, Edited by Pierre Leguillon and Barbara Fédier, which provides a collection of historic and contemporary examples.

The Goya detail helps us see how calling cards connect the 18th century with the 21st, even while they are just about extinct today. Traditionally, these cards (also known as visiting cards) were used to leave at the residence of someone if they were not at home to let them know that they had stopped by. Their usefulness meets their elegance. Today we don’t need much more than the name of the person we are meeting in order to find them online (unless, of course, if they have a very common name, which then will require one to provide more details). At least in my case, given my mild-prosopagnosia (face-blindness) and terrible memory with names, they do turn out to be very helpful.

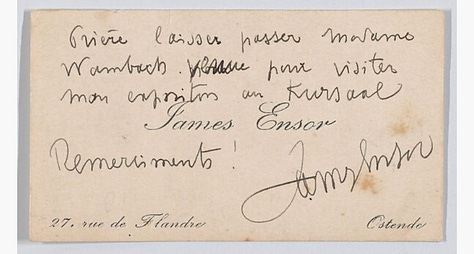

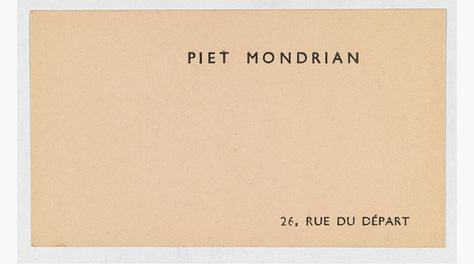

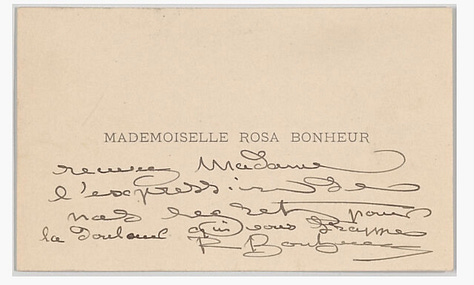

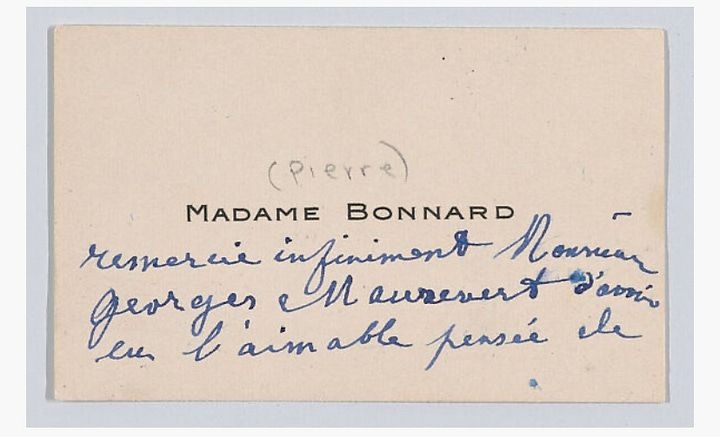

Looking at the historic examples, it is interesting to see that most famous artists had rather boring cards. But the post-war era changed things. As I normally do in exploring semi-obscure topics like this one, I turned to an expert: David Platzker, who is a curator and director of Specific Object, which is self-described as “a gallery, bookstore and think-tank dedicated to art post 1959 specifically pop, Fluxus, minimal and conceptual with an interest in the art that informed the 1960s and 1970s, as well artists whose works organically followed from the era.” I asked Platzker to name a few artist business cards of this period he could recall. Among various examples, he pointed to Claes Oldenburg’s various colored cards he made for The Store, a project created by the artist in 1961 in the Lower East Side of Manhattan; the cards that Ed Ruscha and Billy Al Bengston made for each other as part of a performance and artist book project titled “Business Cards” in 1968, and also the card that Louise Lawler designed for Dan Graham. According to Platzker, “Louise told me Dan asked her to make a card before Dan went to Japan and insisted it was important to have a card he could formally exchange with the people he met. Louise put a pavilion on the verso so people could associate Dan with his works.”

Alexandra Mir, Platzker also added, used the business card as an announcement device for a project, which reminded me that for a short period of time some artists and even galleries used the inexpensive process to announce exhibitions, a strategy used by Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago for about a decade starting in about 2004, when they were an emerging gallery. As Meloche herself told me, “we went to our mini business card format trying to differentiate our young gallery from the pack.”

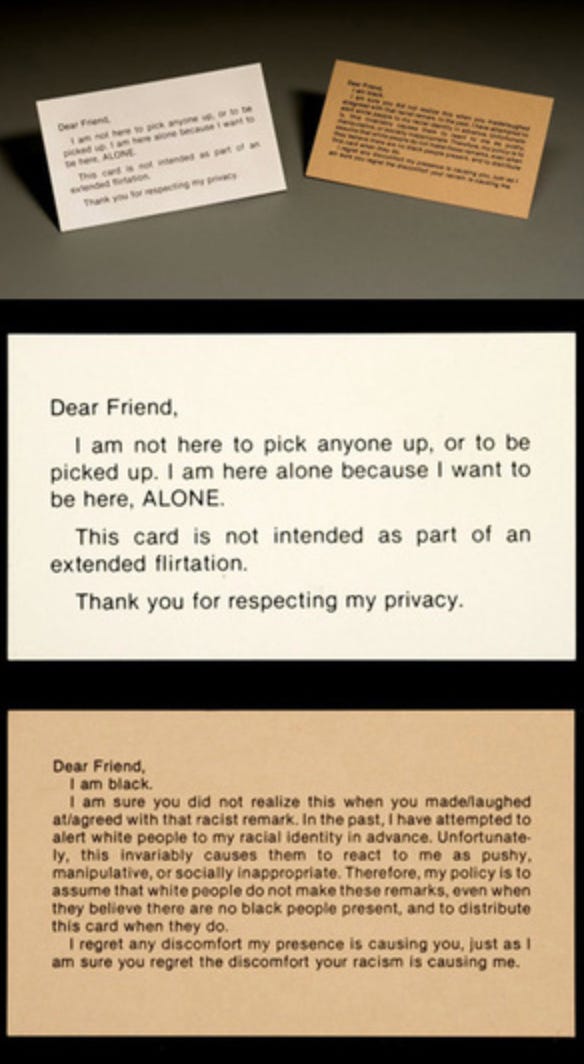

Of course calling cards like any other form of communication have been subject of all sorts of artistic uses such as confronting harassment or racism, as in the famous case of Adrian Piper’s Calling Cards. In Calling Card #1, the artist confronts the stereotype of a woman being alone at a bar to state her desire to be left alone and not interested in flirtation, while in Calling Card #2 where she calls out on strangers who have made racist remarks in front of her, sometimes not realizing she is Black.

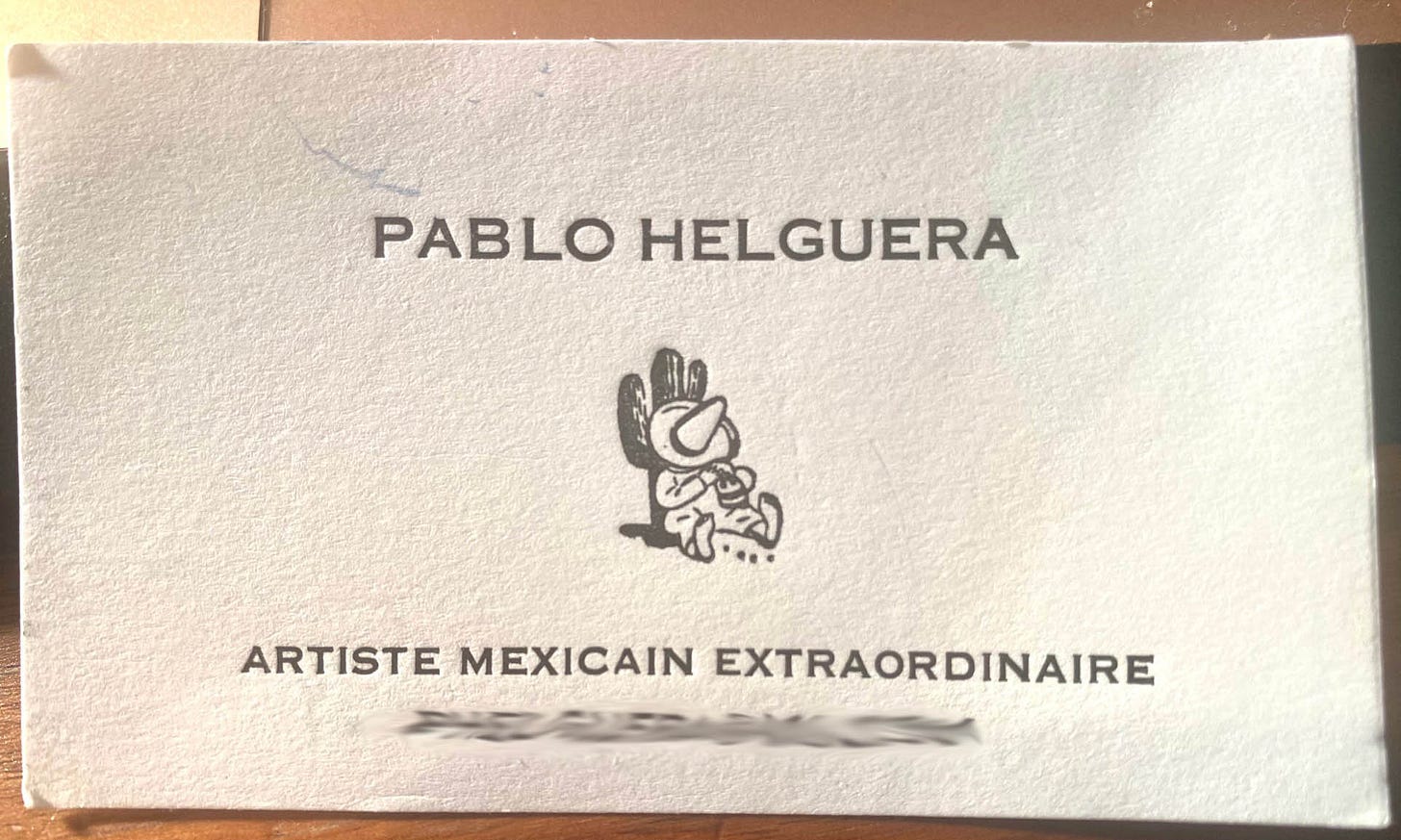

Business cards forced me to face the conundrum of my double identity. At every museum job I had I would receive a nicely designed business card with my email and phone number. While it was nice to give those out, I was also messaging that my primary identity was the one of an arts administrator, not an artist. So I tried a whole range of workarounds: I printed my artist information on the back of the museum cards, I created artist cards of my own, etc. A friend of mine who had worked at MoMA as a curatorial assistant kept her museum business cards and violently scratched the museum’s information on each one, with a stamp with her current email- a gesture that meant to imply that she was now institutionally free but also signaled (at least to me) her inability to move on.

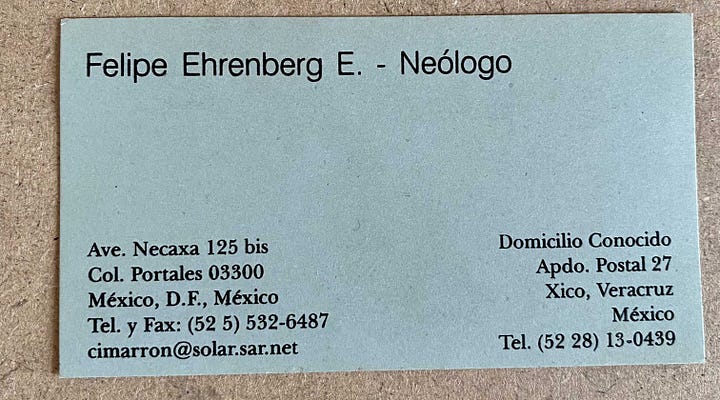

I always liked to see how the conventions of the business card offered fodder for artists to use it as a medium. As a young performance artist, I once went to a lecture by Ping Chong in Chicago and approached him at the end in the hopes to stay in contact. He was very friendly and accessible and gave me his business card. But as he was about to give it to me he stopped and said “No— wait: I must give it to you in ceremonial Chinese fashion” and thus proceeded to hand it to me with both hands, as an offering while he bowed, smiling. It was a micro-performance that I still remember to this day. Another convention, often subverted, is the idea that the card is a sign of someone’s profession. As an example, Mexican artist and the informal dean of Mexican conceptual art Felipe Ehrenberg had a business card that said “Neólogo” (Neologist), a fitting descriptor for someone that sought to reinvent art and its relationship to language.

Here I should mention that the Plaza de Santo Domingo in Mexico City still to this day is a wonderful place to go get business cards- many small printers stand around with their machines and can make you a set of calling cards or business cards in a matter of hours:

I saw the business card as an opportunity to offer not just information but also provide a small artwork (in Spanish we say, “como muestra un botón”, which means ‘a button as a sample”, which means that a small part can be representative of the whole). Yet I am sure I could not have been the first, not will be the last, artist to make a business card as an object label that also was a work into itself, which in my case contained the following text:

Pablo Helguera (Mexican, b. 1971)

Untitled, 2005

Ink on paper

Gift of the Artist

The problem I had with this model of business card was that it was not always processed properly while going through the stages of data entry. At some point, I suspect, a distracted intern, while transferring the information onto a mailing list somewhere, added “Gift of the Artist” as the name of a business. So for several years I received snail mail addressed to me as the director/owner of Gift of the Artist.

I have not carried cards of any kind for years, and also have been slow to transition toward digital business cards of the kind you put in your Apple Wallet— a double failure that gets me in trouble with both old-school and high-tech people. An older art consultant who I had lost touch with and ran into an opening recently asked me if I could put her on her mailing list. I told her I no longer send mail (nor even email) announcements, which really disappointed her. I told her that I post things on social media which she told me she abhors. In the end it was clear to both of us, busy and stubborn New Yorkers, that the divide was unbreachable.

But I should add that, as one ages, elusiveness gradually becomes more appealing. I am fond of Michael Rakowitz’s philosophy on the matter: a friend and great artist who I admire, he is hard to get a hold of (and he is not on social media). If you ever get your hands on his email and contact him, you might sometimes get an auto-response explaining that he is not reachable, busy with personal and/or professional matters. “If you really need to reach me”, he wrote at some point in one auto-response, “be creative.” Which might be a good excuse for me, next time I need to get a hold of him, to still keep a set of calling cards of my own so that I can drop one off at his gallery.

Pablo, I love this. I too used to make cards back in the day, some handmade, some conceptual. You’ve made me miss the practice. Perhaps it’s time for a revival.