A Lucha Libre Theory of the Art World

Rudos vs. técnicos.

Carlos Amorales, still from Amorales Interim, 1997. Single-channel video on monitor, ’9″43. color with sound. Courtesy of the artist

Since 1957, Roland Barthes has been the go-to theorist for wrestling, which he famously reflected upon in an essay in his book Mythologies, with the opening line: "The virtue of all-in wrestling is that it is the spectacle of excess." While maybe not the first one to observe such thing, he also referred to wrestling as "the key which opens nature, the pure gesture which separates Good from Evil."

Wrestling in the West is mostly derived from the Greco-Roman tradition. Its Mexican version, however, known as lucha libre, “is linked to pre-Hispanic culture. We are a warrior culture”, said artist Lourdes Grobet in an interview. Grobet, who recently passed away in July of this year at 81, was known for her photographs of lucha libre. She recalled being fascinated with lucha libre since she was a child, and when she became a photographer she went to fights in order to document them. “They had never seen a woman taking photographs of the wrestling matches,” she remembered. But in spite of that she slowly gained access and trust into that environment.

Lourdes Grobet, El Santo (all photos courtesy of Lourdes Grobet artchive)

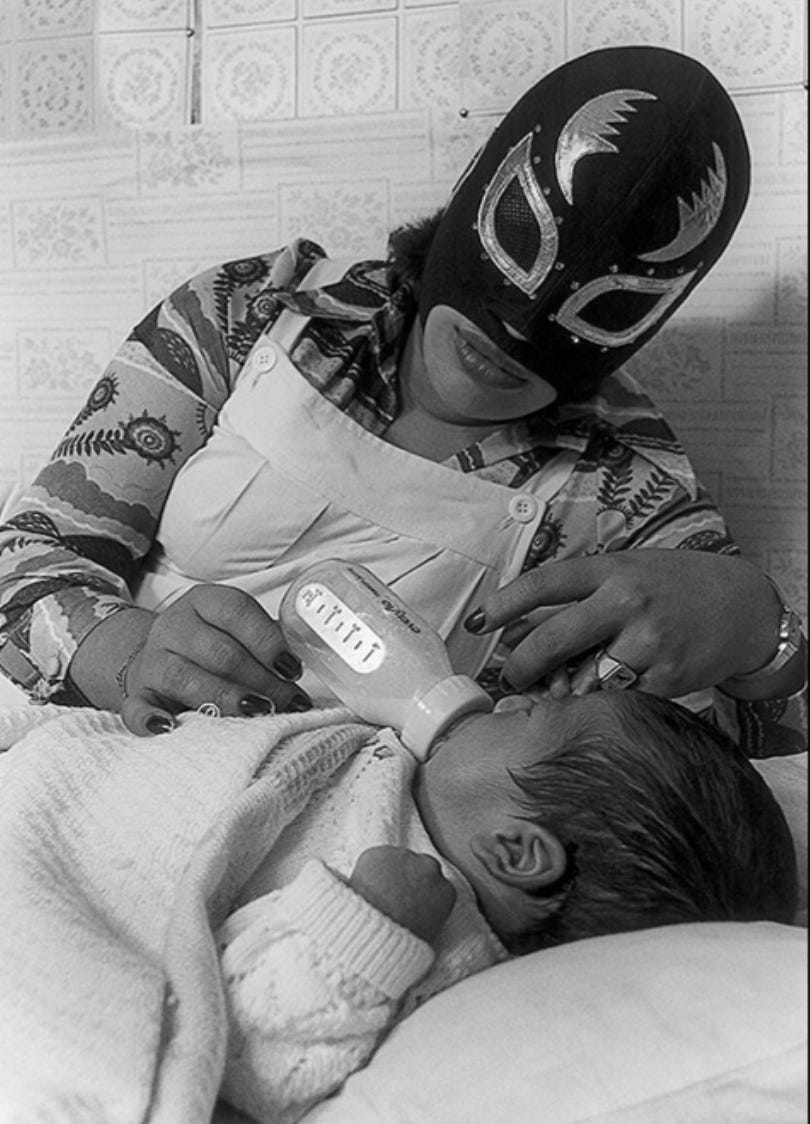

She didn’t want to be an ethnographic photographer, “a folk photographer”, as she described the work of other Mexican photographers who would document indigenous traditions and rural life in Mexico. In her view, “my urban Indians were the wrestlers.” And document them she did, often photographing the private lives of the wrestlers, the majority of which had daytime jobs: teachers, dentists, dancers and more. They would take their masks off in the privacy of their homes with their families, although she notes that the two most famous lucha libre idols, El Santo and Blue Demon, “are the only ones that I never saw their faces and I never wanted to see them.” Grobet’s documentation of the lucha libre world also made visible another facet of it that is not so known for those outside of it: the life of women wrestlers. Grobet documented several female luchadoras, many of which could be the fiercest fighters on the mat while being caring and dedicated mothers at home.

Lourdes Grobet, La Briosa (from the series La doble lucha (The double struggle) , 1981–2005

Lucha libre is a complex cultural phenomenon, one where the spectacle of fiction and the measurable parameters of conventional sports are intertwined ( “it is a mask culture”, Grobet said in that interview, referring to how appearances can be deceiving in that universe). But separate from that is the performative choreography of the sport (or the art?), which historically was divided into two camps: rudos and técnicos. “Rudo” which literally means “rough”, refers to wrestlers who play the role of a villain, brawler, or a rule-breaker, also known in pro-wrestling as “Heel.” Rudos rely on brute force or overwhelming physical power (think of Hulk Hogan). The Técnico (or technician, in US Pro-wrestling the term used is “Face”) on the other hand, play the role of the good guy, or the expert that abides by the rules and emphasizes strategy.

Because of the interesting divisions, symbolic meanings and intricacies of wrestling prove useful when you use them to understand other worlds— for example, politics. So why not try to understand the art world using a lucha libre analogy?

The most basic similarity between lucha libre and the art world is that, aside from their competitive nature (like the one of any other profession), and in spite of the fact that both fields reward practitioners with prizes and other accolades, they are much more subjective than objective, much more about performance than sports. And just like in lucha libre, there are two complementary styles of performance in the art world: its own version of rudos and técnicos. If you are involved professionally in the arts (and I assume you are likely to be, since you are reading this column) you might want to know which type you might be.

The rudo in the art social system is the type who is naturally infused with creative impulses, intuition, and instinct. They are deeply engaged with the present, but they are in for change. They are rule-breakers, paradigm-establishers, and some can be visionaries. On the downside, they are not great at following-up, at meeting deadlines, at filling out forms or at getting groups of people organized. They are often made fun of their absent-mindedness but their raw ideas matter and can inspire others.

By now you might have guessed that I am speaking about artists. But not all rudos are artists, nor are all artists rudos. There are also rudos who work professionally as curators and critics.

I recall a famous rudo curator who is beloved and admired for his intellect, yet also known for this extreme absent-mindedness. While brilliant, he was always late to meetings and was (and still is) largely impossible to find. He also refused to use a cell phone until about a decade ago, when his exasperated assistant insisted on getting him one so they could know where he was— yet he was uniquely inept at learning how to use it. One time, when he was (as usual) incredibly late to a meeting, he desperately scrambled looking for his phone in his apartment in order to alert people he was running late, and then jumped into a cab. He didn’t know how to even make a phone call, so he asked the cab driver to help him with it. When he handed the device to the driver, the cabbie burst out laughing. “This is a remote control!” Another noted curator I used to work with was a born rudo, who loved to talk in meetings as if he was thinking out loud, describing his visions. After a meeting with him, my coworker was totally exasperated with him, saying to me: “he just shows up to meetings asking us to organize his brain for him.”

The técnicos in the art world are those who specialize in establishing structures. They are strategic thinkers and are those that everyone turns to when they want something to get done. They are excellent engineers of procedures, good at keeping track of budgets, using Asana, taking notes and sending minutes after every meeting, and thinking ahead just about every single potential issue and quickly problem-solve. Their challenge is precisely in creativity: while exceptional in gathering and analyzing information, they are not wired to think in imaginative and original ways.

Conducting artistic personality tests at Café Sperl, Vienna, 2009

I am not one to be able to argue for the scientific accuracy of personality tests (although I have long been fascinated by them and in fact back in 2009 I created an art personality test using the enneagram system). However, looking at the simple dualism described above might help us understand how the way we are built, as well as our inclinations, strengths and shortcomings fall somewhere in between these two areas. I, for one, recognize that I was born and raised as a rudo, and spent all my professional life learning how to be a técnico. While learning to be organized as a creative individual it is a very difficult process, it seems to me that there is nothing more difficult than the opposite: learning to be creative. I used to oversee someone once who excelled at técnico work but wanted more responsibilities (e.g. a job promotion). I asked her to tell me her ideas of her own for new initiatives we could put forward. She was unable to come up with a single one.

I have even seen it in the case of artists who excel at being técnicos and, because they can’t generate a rudo type of output, they then generate técnico-style work dressed as rudo. It doesn’t work (and I apologize for not being able to explain this further nor give examples, but I can’t name names).

Lourdes Grobet, Blue Demon, 1980

This simplistic definition of course is nothing other than that: a simplistic definition. But when we think of the art world in this way it might allow us to recognize two things: first, that art is an ecosystem where every art project is in fact a collaboration of rudos and técnicos. This is literally the case of various collectives (even pairs of artists) when one of the halves covers one area while the other half covers the other. It is also the case of the lives of many artists who might not have become known if it were not for the support system around them, or for someone who gave structure, meaning and visibility to their work. And secondly, and going back to the performative, spectacle- based environment of lucha libre, art indeed is a performative engagement of instinct and strategy, one where, whichever mask we have decided to wear (artist, curator, critic, dealer, etc.) we need to go through a process of understanding our unique characteristics and play to our strengths.

The one artist of my generation, as well as a friend, who has dealt with issues of identity and performativity in lucha libre is Carlos Amorales, who came to international renown for his videos of the masked Amorales vs. Amorales — a work that highlights both the performativity and the incongruity of antagonism in life (and, I would add, in art). In the end, identities in the larger social choreography of art dissolve—we all are less unique than we think we are. I asked Amorales whether he saw lucha libre as a metaphor of the art world. His response: “at least that’s how I saw it when I started with the project of making myself a double as a wrestler, where I as artist saw myself as equivalent to to the wrestler, the dealer as the manager, and the exhibition space as the arena. Nowadays I realize that the art world is more complex, but I think it was a good start.”

Lastly, a detail that I think works in support of the técnicos/rudos theory: when I asked Lourdes Grobet’s daughter, the artist Ximena Pérez Grobet, what camp did her mother favor, she replied: “I believe the rudos.” But after asking the same thing to Amorales, he went further: “neither one nor the other: Amorales, always Amorales!” Which could be interpreted, I think, as a rudo-style response.