BTW, FTW, ILY, CYA, NSFW, FWIW. These basic Gen Z -favored abbreviations might appear largely impenetrable to those of us who belong to older and increasingly receding generations; but in reality this seemingly insider-y language is the result of a dynamic that has been going on for thousands of years. We refer to it as shorthand.

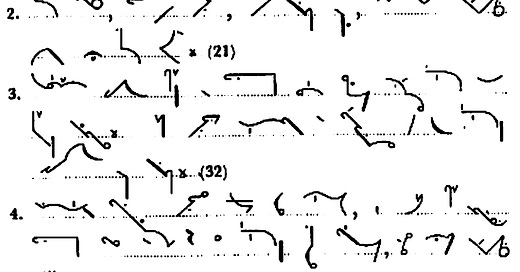

Shorthand goes back to ancient Greece and Middle Egypt. In ancient Rome it emerges about 60 BC with Marcus Tulius Tiro, who was Cicero’s slave (later freed) as well as his personal secretary. Tiro confronted the problem of how to quickly and efficiently record the sprawling speeches of the author of De Oratore. According to Plutarch, Cicero worked with Tiro and other “rapid writers” to quickly transcribe the speech of Cato the Younger during an important trial. The resulting quick strokes of word stems (notae) and word ending abbreviations (titulae) became later known as Tironian notes, which reached to be about 13,000 symbols.

What interests me about these verbal shortcuts (be it Tironian notes or modern stenography or 2020s teen texting) is not necessarily the socio-cultural-technological dynamics that generate them, but the fact that the necessity of expedience that motivates their creation is not only social but also applies to facilitate intellectual research. This is an education problem, in fact: since the discipline is primarily concerned with the processes and methods of transmission of knowledge, of paramount importance is how we come up with efficient methods to facilitate this transmission. And for those who doubt it, I would point out that the inventor of modern shorthand was, in fact, no other than an educator: Isaac Pitman.

Pitman, a British English teacher who advocated for the spelling reform of the English language believed that "time saved is life gained.” At only 24 years old he invented the symbolic writing method titled Sound Hand, a system to quickly transcribe the spoken word, now known as stenography. Pittman is a fascinating figure not only in the spelling world but also in the history of education: in the 1840s, when uniform postage rates were established across England he also became the inventor of modern-day distance learning by teaching the Pitman’s system via mail, sending, receiving and correcting student lessons.

So from its inception shorthand has been officially about expedient recording, but it also has been about synthetizing concepts— something that becomes even more vital when we are trying to describe complex processes or articulate problems. The ability to quickly reference ideas that are already agreed upon is hugely helpful in order to build something new.

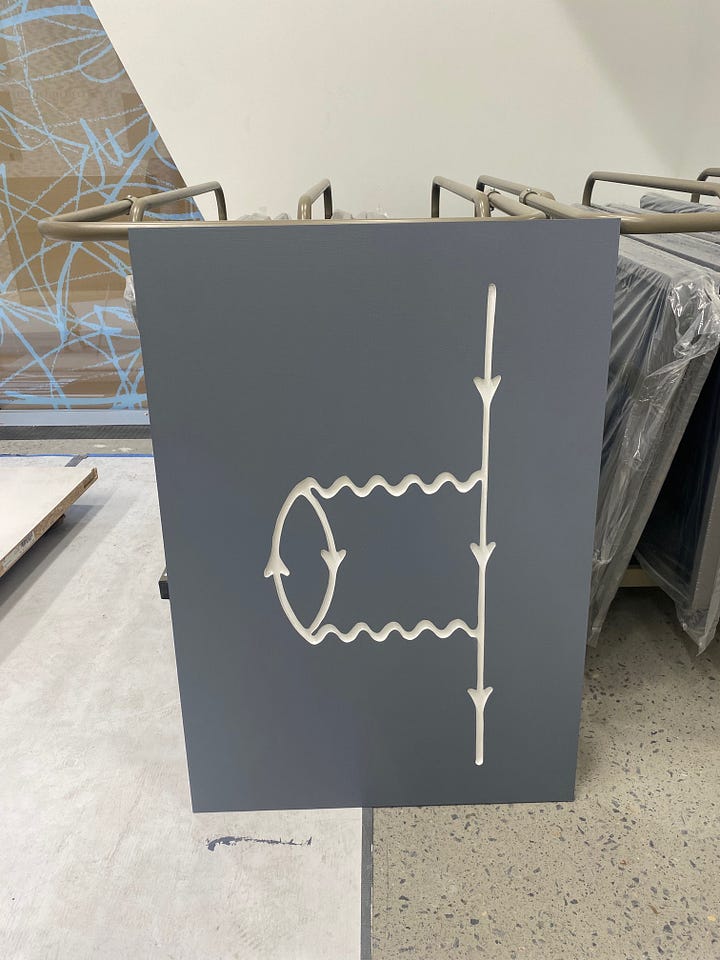

About ten years ago, when I was doing research for a public art project at the Far Rockaway Library in Queens, I realized that the nuclear physicist Richard Feynman was a native son of that area. Feynman, a Nobel prize laureate considered one of the most important nuclear scientists of the 20th century, is also known for the creation of the Feynman diagrams, which are visual representations of complex common interactions between subatomic particles. Before these diagrams, describing these interactions would be an arduous and difficult task for scientists, involving a lot of math and equations. In 1948 Feynman invented, so to speak, a shorthand for quantum physics that revolutionized the field. It is still used today.

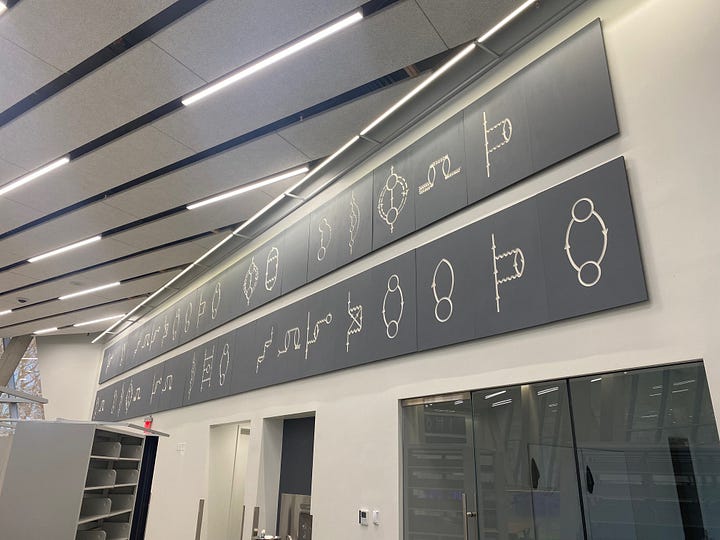

During my research I was also very moved to learn of Feynman’s passion in learning about the world and out position in it (“I, a universe of atoms, an atom in the universe” is one of his famous phrases). The Feynman diagrams are a visual/written decoding of the language of nature, so they seemed to me appropriate to present at Feynman’s native place in a building whose function is to help us read to understand the world. The library project uses each symbol as a stand-in for a letter of the alphabet, so that one line reproduces the famoud Feynman quote and the other a quote by Emily Dickinson, “The mind is wider than the sky .”

Ever since I worked on that project (now reaching the launch phase) I have been wondering about how we could create a version of the Feynman diagrams for art. The two fields I have background in, —education and humor— require one to be a concept synthesizer. Further, as artist, and not a, say, art historian, one’s interest lies not in streamlining the understanding of events, processes or concepts of the past but in creating methods to understand present processes that might then result in something new. Mainly, I wanted to know if using a pedagogical approach (what I often refer to as Transpedagogy) I could create a system that would help individuals interested in understanding a problem, developing a research question, or even organizing a debate or conversation, to do so using images. Each image would de descriptive of a communication, cultural, or philosophical term or archetype (intersubjectivity, colonial legacy, agency, etc.) which help formulate useful questions for research.

But how to go about such enormous task? As evolutionary scientist Richard Dawkins often says you need to start with simplicity and work toward complexity; you can’t ever start with complexity (which is incidentally one of his key arguments against theism). A complex fugue starts always with the exposition of a simple subject: a melody, which then is followed by a countersubject and is built upon in complexity. So I thought I would start with the alphabet.

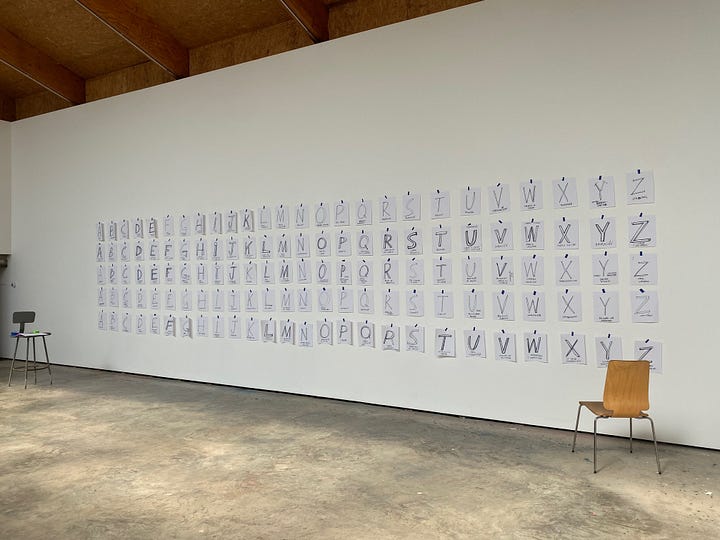

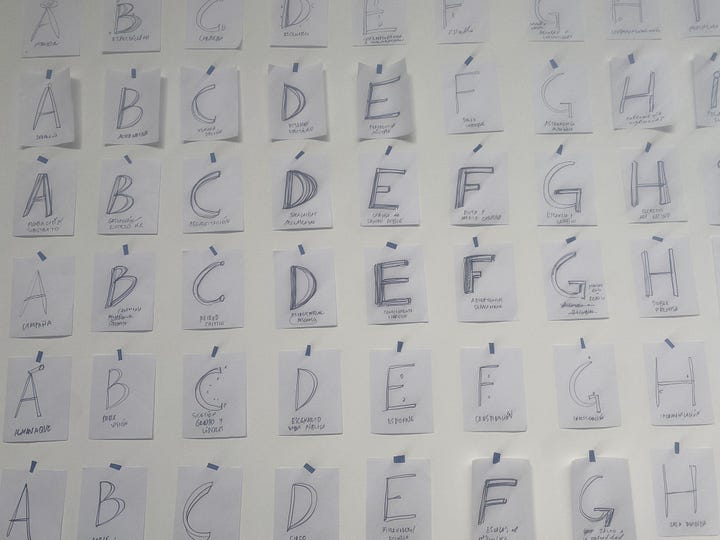

For each letter I wrote six concepts of processes, communication scenarios or that the letter prompted in my mind (I worked using Spanish). Over a process of rewriting and redrawing I slowly worked toward an image and a word or phrase that synthesized each one of those concepts. For example, the letter “D” represented in my mind a stage (given the image of the letter), but also a platform and departure point for an exchange or experience; it also stood for a public encounter and/or a presentation of that encounter, plus a site for dialogue (per the “D” in “dialogue”).

The final resulting pedagogical concept is “audiencia”, which stands for collective work, group discussion, or the process of public dialogue and collaboration. Following the same process, the result were 26 icons/concepts based on the 26 letters of the alphabet (excluding “ñ” of the Spanish alphabet which seemed too orthodox for this process).

The card set is used in three stages. For each stage the participant is asked to pick three cards- either by chance or by deliberately picking the images that interest them. In the first stage, the participant is asked to think of a question or problem that they are professionally involved in (e.g. that the participant has professional investment and a degree of detailed knowledge of the problem) using the cards . The second and third stages, consisting in picking three more cards, concerns the possible aspects of the problem, moving toward the central objective, which is to articulate a useful research question. I playfully named it “Método de discursos sociales”, a game of words with Descartes’ Discourse on the Method, it being a step-by-step process to understand something, but instead of using 17th century deductive reasoning the system allows for intuitive inferencing, which is natural to use when you are working with images. In contrast to the Feynman diagrams, which are shorthand references to very specific processes, the images here are somewhat open to some interpretation and will change depending on which cards/images are next to them. Thus if I use the card/image D, “audiencia” next to A, “faro subterráneo” (“underground lighthouse”) the operating concept could be audience research, the need to understand why public opinion veers in a particular way, or other idea around evaluation.

This set of cards is not meant to function obviously as a divinatory device, as there is no predictive or spiritual aspect whatsoever to this process. However, the chance element is important and can be put to good use. Chance processes can support what we sometimes describe as differentiated instruction, which is a term that basically refers to how every individual needs a different path for learning. In this case, the aspiration of this card set is that all roads can lead to Rome— at least in the sense that the set can help construct a road map for research. Having a system where there is the option of increased structure and freedom depending on the participant (e.g. that the person chooses the image vs. picking it up by chance) is like giving a choice between the winding road or the highway to the same destination.

As I put together the final aspects of this project, which launches today as part of an exhibition in Mexico City, I had a flashback to my own college art education.

The most important teacher I ever had at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago —and who I have often referenced in my writings—was the eminent professor and art historian Robert J. Loescher— whose voluminous body felt as an indicator of all the art historical knowledge he contained. He was the ultimate synthesizer: he had been the editor of the arts at the Encyclopedia Britannica for one of the early 1970s editions (he once recalled how when he and other editors started on the project to build the initial index the chief editor had told them: “you have four weeks to assemble the entirety of knowledge in the world.”) He was an expert lecturer, but his true gift was to make us speak— thus him becoming a sort of attentive and deft therapist.

After I graduated we kept in touch, a friendship that lasted nearly 20 years. As he was nearing the end of his life, I would sometimes pay him a visit at his home in Chicago. We would spend hours talking about art, exhibitions, artists, and more — Bob loved to gossip as well. “It’s becoming so easy to talk to you”, Bob told me one day. There were so many people, places, art works, exhibitions, publications and ideas connected to all of those were things that we had experienced over the years of which Bob and I knew that the other knew. So our conversations would be very fluid and fast-moving, and probably largely incomprehensible to an outsider (“You know, that artist who did that show that we talked about the other day that our friend wrote that piece on”, etc.). This shorthand conversation approach would be even more natural for a man whose job was to compress all art knowledge in a single publication, and who was famous for also offering rousing art historical lecture that would perfectly encapsulate decades of cultural and political events in matter of minutes. I recall as I grew older and happened to attend a few of Bob’s classes merely for personal enjoyment I started to notice him giving a few inexact dates, titles, and names in his lectures. But his lectures were more about texture and narrative than about detail, giving us, more than information, a love for the subjects he taught. As Maya Angelou famously said once: “I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Going back to pedagogical shorthand, my point of Bob’s story is that the successful process of education is by necessity one where both intellect and emotion interact, as well as one where the student has the agency and motivation to know something. The educator can explain the meaning of a concept (e.g. in shorthand), but these only become the bricks to build something new. And this is a crucial question that artists today need to ask ourselves in terms of our production: do we want to continue in a tradition of making objects meant to be worshipped, or do we want to leave works that could be tools that others can use to build things on their own? Art-as-education, as a conceptual process, I would posit, is about the latter, and shorthand is only a practical (and age-old, but evergreen) way to establish the consensus of the concepts of the past to construct that which is not there yet. IMO.

Brilliant as usually, totally mind invigorating reflections! How do I purchase the Metodo de Discurso sociales card set please!!!!??