In the summer of 1995, a time when I had recently left museums to focus on my studio practice and was in need for a steady income, I took on a temporary office job in the Chicago suburbs. It was at a trade publishing company that made industry-specific magazines, and the one I worked on, published in Spanish, was for the food-processing industry. My job was to review dozens of press releases about production, processing and distribution of food products, summarize information and write small articles about new equipment for food production and market trends. It was a mind-numbing, infinitely boring job in a 9 to 5 cubicle in a typical corporate office. The 1999 movie Office Space, perfectly reflects the absurdity, pointlessness and overall alienation of that period of my life.

I also had a studio in downtown Chicago, in the Fine Arts Building, a beautiful Art Nouveau edifice decorated with turn-of the century murals painted by Illinois artist John W. Norton; an interesting contrast with the gray, nondescript suburban building I worked at.

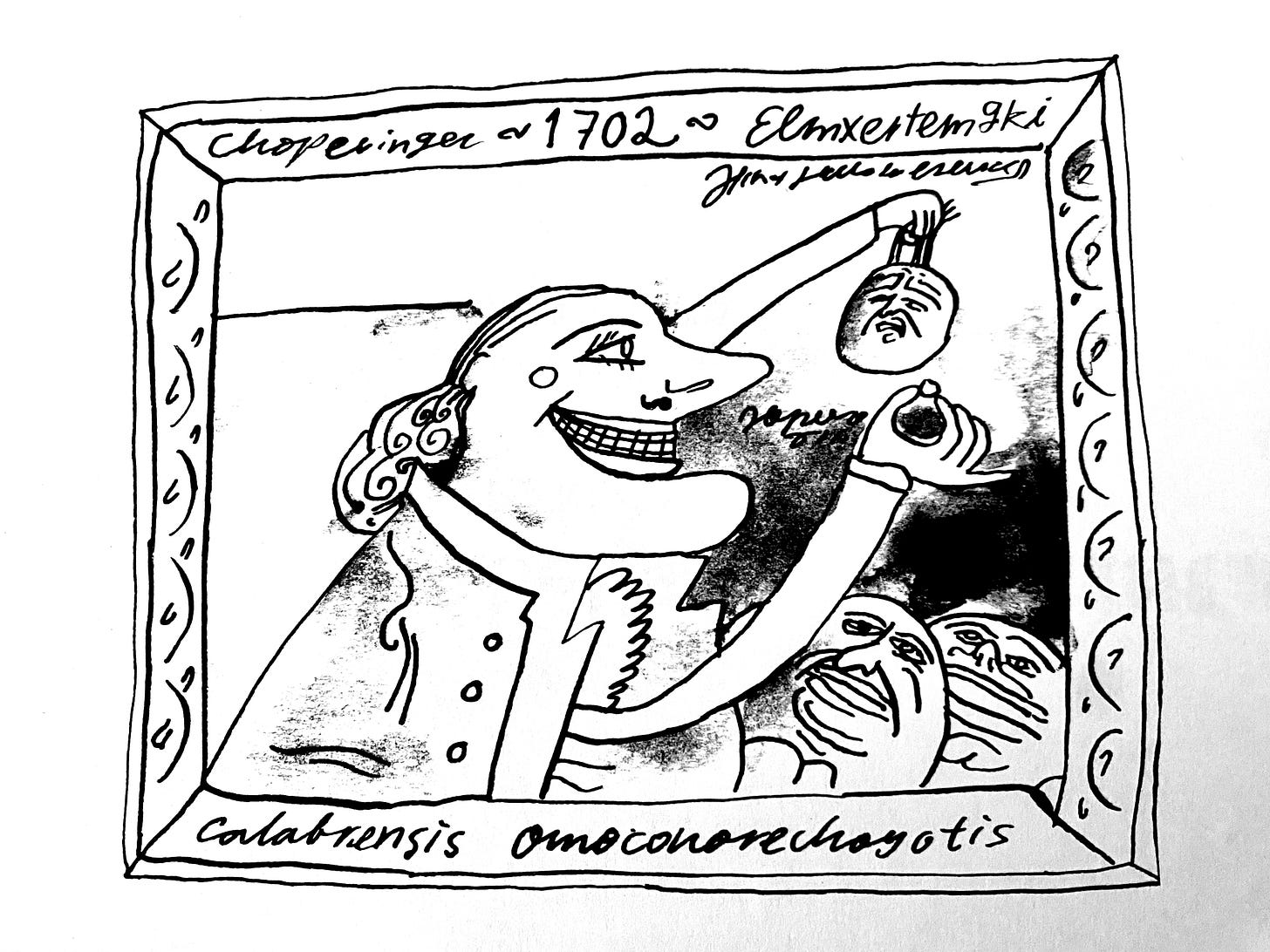

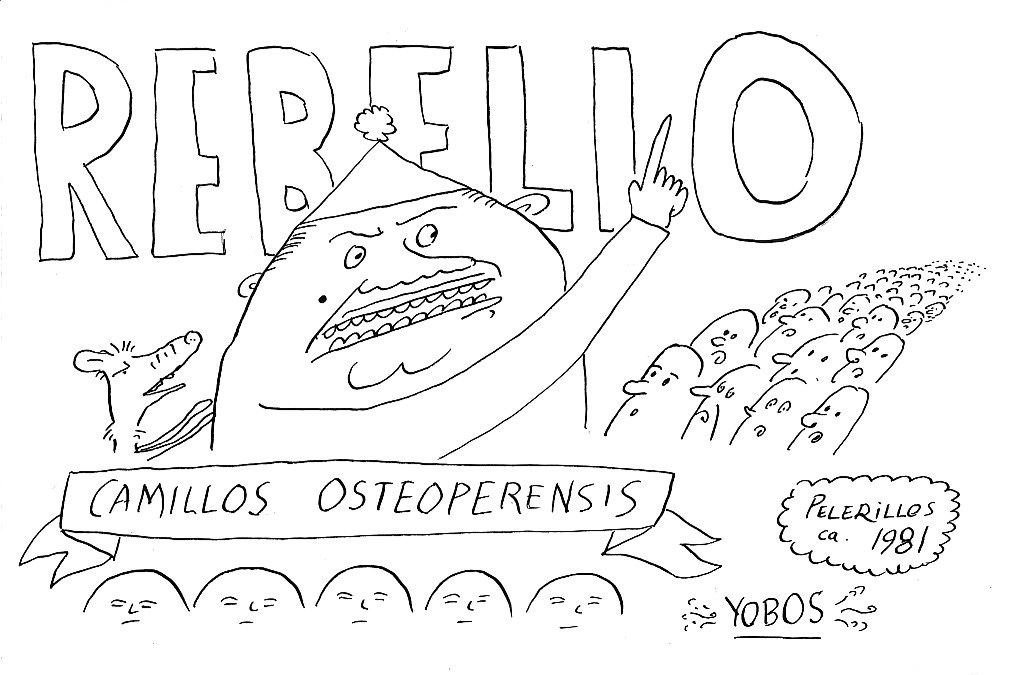

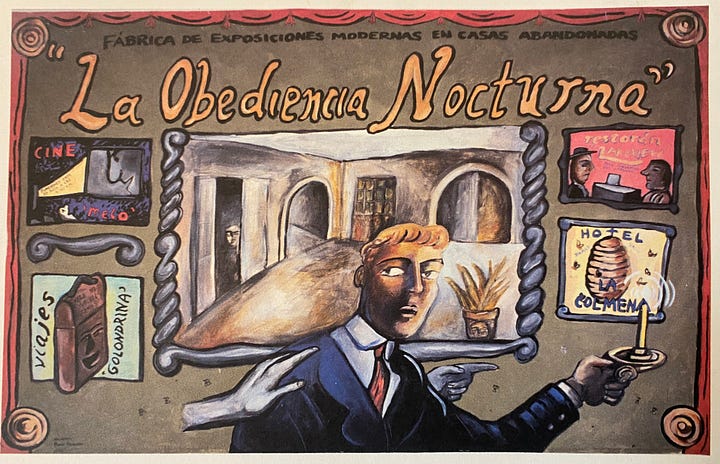

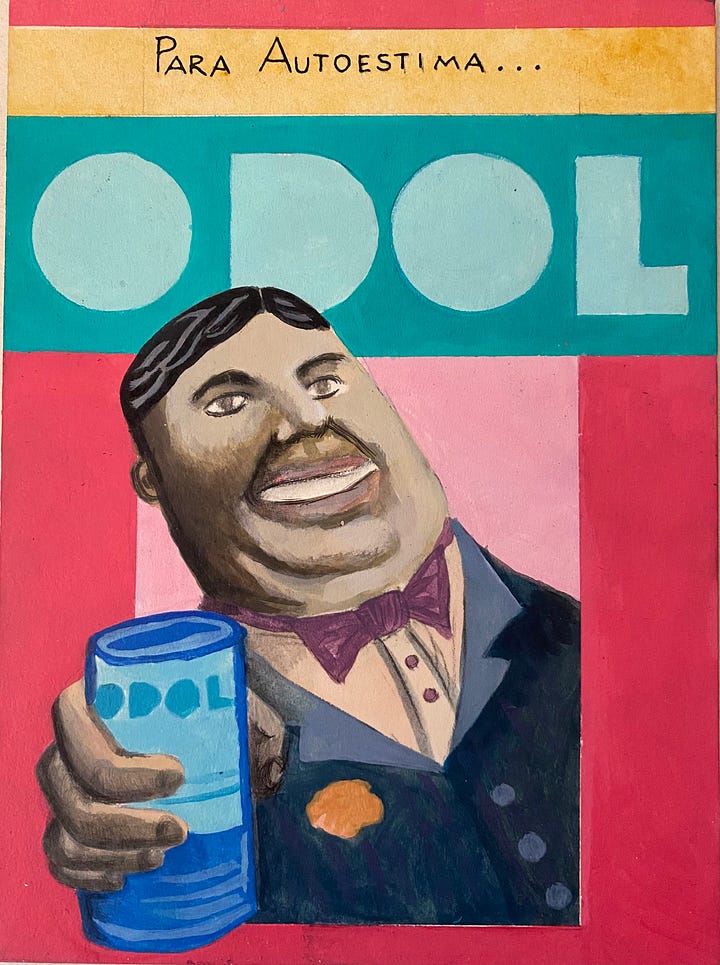

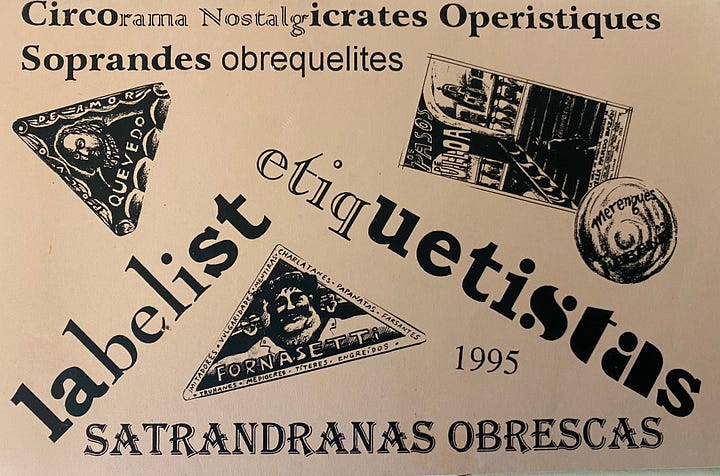

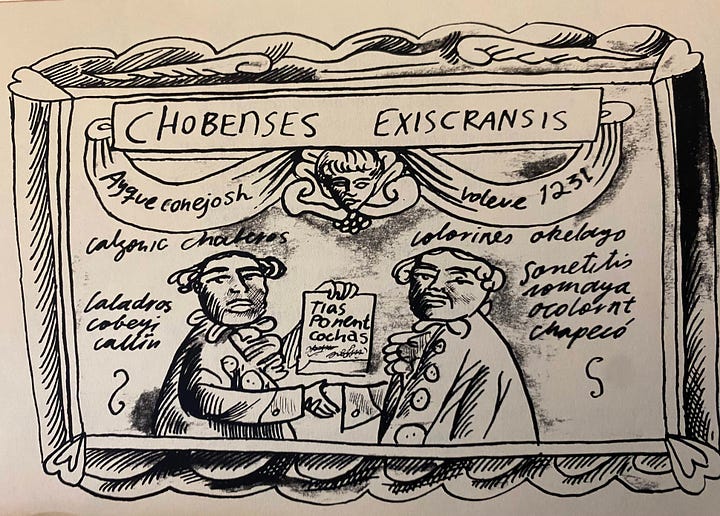

During those years, I was contending with a number of problems as artist. While I had enthusiastically embraced performance art, I still had not yet fully absorbed, not really understood or appreciated, conceptual and process-based practices. I felt isolated and stuck in a corporate job that was light years away from where I wanted to be (even while I had no clarity as to what that place was, I was certain that I was in the wrong place). I felt powerless. I was angry and frustrated by the vapid and meaningless office job I had to do, and by the stupid rules and goals that governed it. I thus started making nonsensical press releases, ads for products that did not exist, and circus-like banners that advertised places but were rather announcements for specific states of mind. What I think I was doing at the time was trying to achieve resolution to conflicts using the absurd as a both a tool and a defense mechanism.

What I drew from was my sense of humor and the absurd, which had always been my refuge; but I also sought to draw from the psychological intensity and the fascination toward the vernacular of a good deal of Chicago art, particularly the work of the Chicago Imagists, some of who had been my teachers at the Art Institute. Curators winced at my work during those years; A critic from that time, likely trying to present my work in the best possible light, wrote that it was not contemporary but 'ontological.' At the time, this hurt me deeply, though in hindsight, she was probably right: I was in a pre-conceptual phase of my development. Regardless, I often revisit the blend of nostalgia and anger conveyed in those works and find myself wondering what, exactly, it was all about.

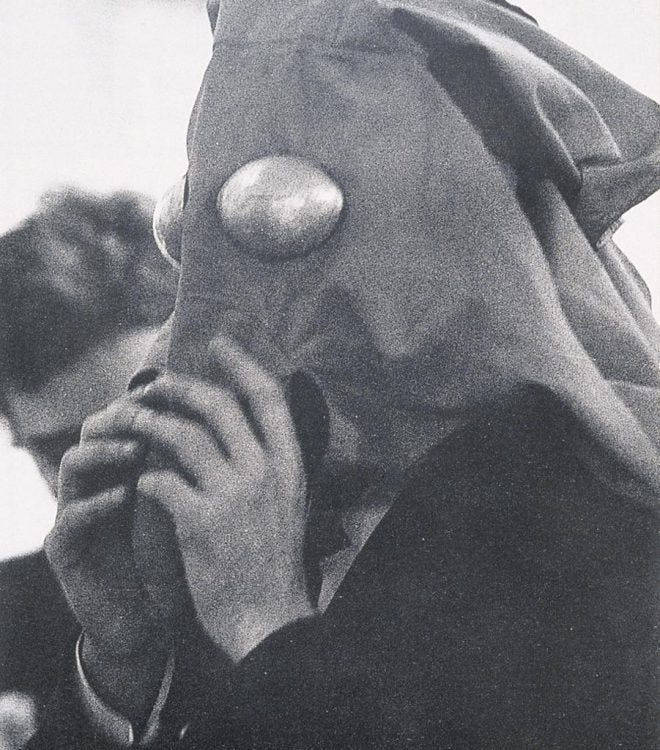

I now realize that I was trying to clumsily navigate a path that Lygia Clark had already figured out and masterfully solved through her work. Clark was interested in the world of the Austrian-British psychologist Melanie Klein (1882-1960), who developed the Object Relations Theory, which dealt with how we internalize aspects of our relationships (primarily with caregivers) through objects, and how we resolve ambivalence (love-hate relationships)by interacting with objects (whether symbolic like the image of the mother or physical like a security blanket). Clark explored the body-psyche relationship first with the creation of her relational objects, and later, of course, with her therapies.

However, my jump into absurdity was not informed by creating interactive objects per se, but by making these imaginary products that contained, in some strange way, disillusionment and contempt for the world I was living in. It was as if my humorous self had descended into hell and was forced to continue laboring, thus resorting to dark humor.

Absurdity and exaggeration are powerful tools that foster relatability. When we encounter something extreme or ridiculous, we laugh—and that laughter signals our shared recognition of the common reality from which this exaggeration springs. This dynamic is central to many Borat films, where subversive comedy, dark humor, and the ridicule of political power and ideologies drive the plot. The structure of Borat’s interactions is fairly consistent: it starts with a seemingly ordinary exchange, establishing the character's eccentricities (supposedly stemming from his foreign background). Over time, the people he encounters become increasingly accepting—until Borat begins to push the boundaries of what’s socially acceptable in areas like politics, religion, race, and virtually any other taboo topic. In doing so, he exposes the contradictions, hypocrisies, and power structures embedded in nationalist discourse.

But mostly, absurdism is not about making no sense: it is a form of social/political critique that tears down the dictatorial logic of injustice. This goes from Alfred Jarry’s King Ubu (which is really a perfect avatar of the current MAGA King in its monstruous greed, corruption, irrational whims and vulgarity).

Object Relations theory as applied to political discourse also help us see the insidiousness of nostalgia. We launch into absurdism to ridicule the present world, but the shadow of that process is the yearning of a better one. Are we idealizing it in the same way in which one desires to make America Great Again, dreaming of a perfect world that never existed, and in fact was deeply flawed (like the U.S. in the 1950s)? Or, are we idealizing it in the way in which Obama’s “Hope” campaign was also imbued with a certain 1960s nostalgia for the American dream and the idealism of the Civil Rights movement? Last but not least, this idealization of the past is not the province of older generations, but rather of those who didn’t live previous eras (Grace Segers from The New Republic recently published an article about nostalgia among Gen Z-ers, also making the point that it is a feeling that crosses party lines).

Perhaps the best way to dispense with that troubling thought is that one should accept, while in absurdist practice, that there never was, nor will there ever be, such a thing as a perfect world— only catastrophic versions of it that we need to do our very best to prevent from happening. Call it tactical nostalgia for pragmatic absurdism.