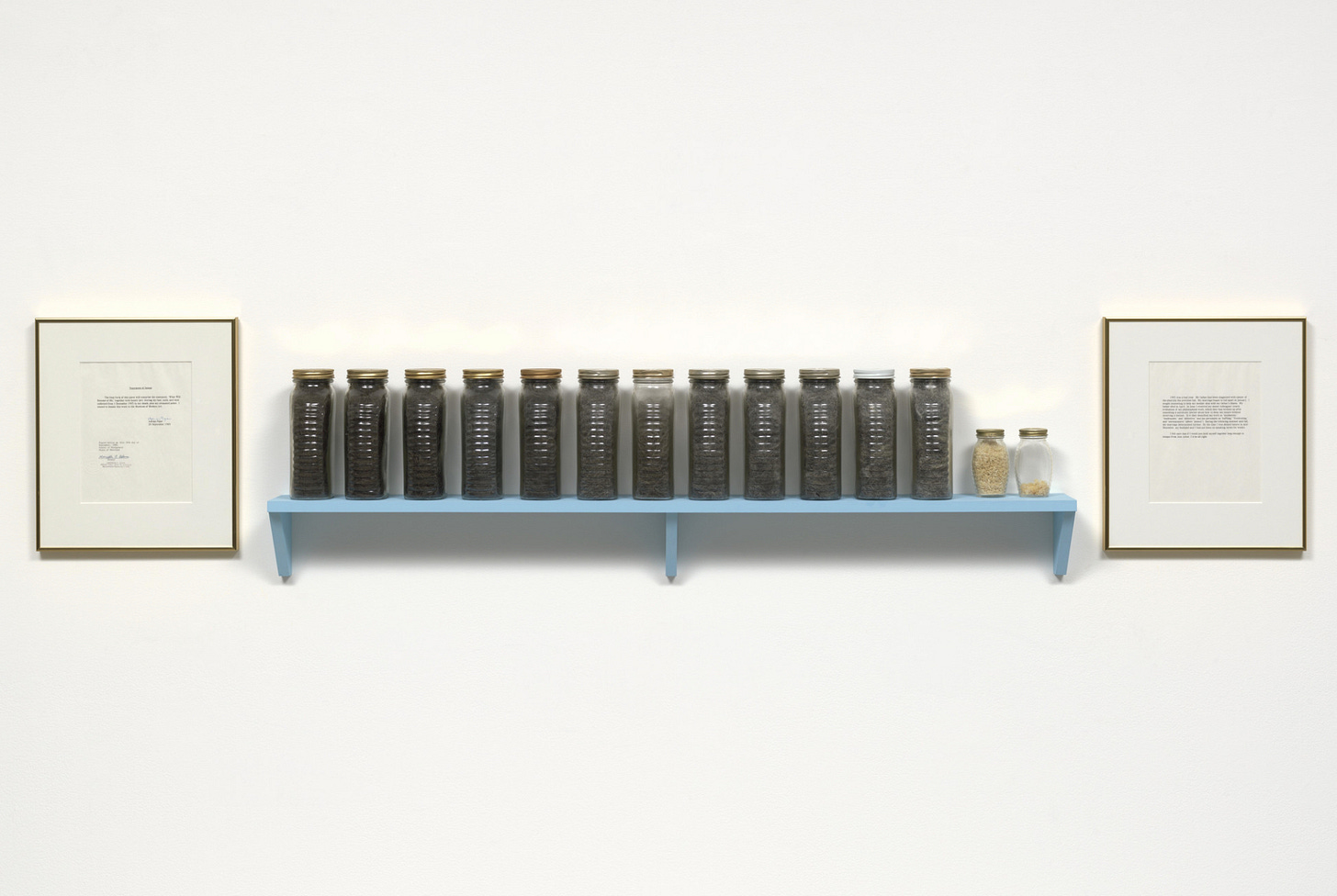

Adrian Piper, What Will Become of Me, 1985-ongoing. MoMA collection

Several years ago I received a rather unusual request from a collector couple in Europe. They had created a museum with a collection of 1200 artist shoes. Could I mail them a pair of my shoes for their museum?

The proposal was simple. The museum had shoes once owned by Baselitz, Panamarenko, Richter, and more— some intervened and others not. But the request being what it was, and artists being who they are, logically the invited artists would more often send their shoes with some kind of transformation, as assisted readymades— since after all an artist would typically like any object coming from their hands to say something about themselves.

I was intrigued by the request, and to an extent tickled by the proposal (I am not a fancy shoe wearer and I have a poor fashion sense, but I could certainly consider making a shoe piece) and at the time I responded positively saying that I would mail a pair. But I was distracted by other projects and forgot about it.

Yet the entreaties continued for years. One day when I was very busy and in a somewhat un-generous mood I received yet one more reminder and I thought about the request more carefully. This time I started feeling slightly irritated by the notion of simply donating my shoes, and face the pressure of either sending an everyday pair of shoes and look boring in contrast with artists who made smart artworks out of this request, or putting a lot of work into it and then mailing an actual work for free.

Finally, I wrote a comprehensive response to the collector. I told them that I had a change of heart as I felt that, given that artists live from their practice, it is important for those who support it to contribute toward it in some way. I would be willing to go through the process of making a work/sending shoes but it would have to be a paid commission.

The collector acted surprised, as if my response were a total rarity. They said they didn’t have a budget and only depended “on the artist’s enthusiasm”, adding, “I understand your point of view, but in fact there is nothing wrong with donating an object (or little piece) to a museum. It’s a pity but we do not have a budget to purchase works.”

This reply really bothered me. From there on the exchange got more heated. I wrote that the fact that an artist’s work (even if it is a utilitarian possession) has some potential value which could at some point be monetized made the expectation of receiving it for free very problematic. Again the collector acted surprised, claiming that “we didn’t ask for anyone to give us a free work, we only have asked artists to give us their shoes.” .

So the misunderstanding was total. After that, we parted ways. And I stored that incident away, but I sometimes think about it because of some of the questions that it poses.

In the collector’s perspective, as they stated, they were not asking for an artwork, therefore the object they were requesting had no art market value. However: wouldn’t an artist’s donation to a museum, whatever it would be, had to have some kind of value since it is being considered worth collecting? It was naïve, if not disingenuous, to think otherwise.

But the key question was how exactly a pair of shoes used by an artist could be considered art, an artifact, or a relic.

Therein lies a conundrum that even the most fervent anti-intentionalist art theorists may not know how to solve: interpreting ambiguous objects that could be artworks or not, especially those made and/or owned by an artist (but not overtly declared as artworks).

While some do not consider that the artist’s opinion has bearing on the meaning of the work, the question is whether we can truly assign meaning, and therefore, value to objects of the artists that were not intended (or that we do not know if they were intended) to be artworks. And the answer is not so simple.

First, there are countless historic objects in encyclopedic art museums that we consider artworks but that we don’t know anything about their makers, their intentions or purpose— particularly from the period that the art historian Hans Belting referenced in his book “Likeness and Presence: The Image Before the Era of Art”. When we look at a Russian icon, an African mask, or an ancient Egyptian portrait we tend to just appreciate it as art, and may not spend too much time wondering if the person who made it saw it as art the way we see it as art today— or at least art in the dominant Western modern concept of art. So given that fact, it is not hard to imagine that there could also be a time when we also think of certain artist’s (and non-artist’s) non-art objects as art; in fact we do so with a lot of contemporary art such as objects owned or made by some outsider artists.

The intentionalist argument would be that one can separate from those objects that have an intention of expression. But there again, we would need to exactly determine what we mean by “expression”, and assess whether something is the result of a specific, artistic expression.

Then there are “relic-adjacent” objects, or objects that we sometime consider artworks even if the artist did not overtly declare them as such.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot is a good example of a creator of “relic-adjacent” art objects. Perhaps the most famous landscape painter of the 19th century and a hugely prolific artist, Corot had the tendency of making impromptu paintings on a wide variety of objects, such as plates, cigar boxes and even his own silk hat. Two extant examples of this practice include a lunchbox that he had made for a friend and then decorated the 3x5” interior lid with his own hand. Another such object is his own paintbox, where one can see something of a sampler of Corot-style images.

Corot’s paintbox (Photo by Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images)

But the more we think of artist’s relics (or relic-adjacent artworks) it is almost inevitable to fall into the more traditional realm of celebrity memorabilia, or rather mundane objects that may be financially valuable (i.e. worth auctioning) because they are anecdotally connected to famous people, but not because they are particularly interesting visually ( just as there might not be anything particularly exciting visually about, say, Gerhard Richter’s old shoes).

I grant that artist’s relics or relic-adjacent art objects might not constitute a totally uninteresting subject, as it may lead to a reflection about the quasi-religious value we may attribute to them, for example. However, I do find it more interesting to think of artists who have explicitly worked with relics as a subject matter or who have turned themselves into relics, as I shall explain.

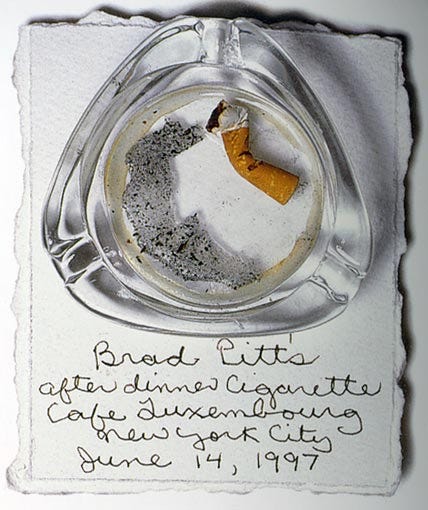

Around the time of my exchange with the shoe collector, a friend invited me to visit the studio of Barton Lidice Beneš, who lived in the famous Westbeth building and artist housing in Manhattan. Beneš was a conceptual artist active in New York from the 1970s until his passing in 2012. In 1986 he was diagnosed with AIDS and over the following decades he became an activist and advocate for the destigmatizing of the disease. He had a unique collecting streak, an impulse that became integral part of his artistic practice. He made “museums”, collecting all sorts of objects connected to celebrities and historic characters, such as a swatch of a dress worn by Marilyn Monroe, a mint sucked on and spit out by JFK, a pen used by Michael Jackson, and so forth. I remember asking Beneš about how he managed to verify if these relics were indeed authentic. As I recall from his response, he did not have any fool-proof method, but he did not appear too concerned by that question: it was the stories behind those objects and the aura created around them that interested him the most.

Brad Pitt’s cigarette in Beneš’ collection

Beneš was meticulous in the organizing of every object—usually not larger than 3 or 4 inches— and would usually attach them onto paper cards with the written description of the item. His tiny apartment in Westbeth was a true Postmodern cabinet of curiosities, packed horror vacui-style with a wild array of artifacts and artworks, by some estimates worth 1 million dollars. The intrepid curator Lauren Reuter, who was then director of the North Dakota Museum of Art and a friend of Beneš, worked with him to arrange for preserving the entirety of the contents of his Westbeth apartment (art, objects, furniture, and everything else) and after the artist’s death had it transported and reconstructed exactly at the museum as a permanent installation as a gift of the artist.

And continuing in the conceptual vein, it is inevitable not to think of artists whose body in the end becomes a relic, or rather, part of the artwork. The most powerful work in that category, in my view, is Adrian Piper’s What Will Become of Me, a piece initiated in 1985 and designed to conclude with the artist’s passing. Since 1985 Piper has been filling honey jars with her hair and nail clippings (the piece is now in MoMA’s collection, so Piper regularly mails the more recent clippings and hair to the museum to add to the work in progress). Whenever Piper may pass on, her cremated remains will be incorporated into the piece and the work will then be completed.

All this to state the obvious: that the deep and complex relationship between contemporary art and relics is worth exploring further (I now present it here as a free idea for a future PhD dissertation. One could come up with an extensive book titled something like: “Almost Art: Relic Adjacency and the Non-Designated Artwork”). Both artworks and relics are the resulting product of a complex set of circumstances, some of them ruled by fate, other times by intention. But in a certain sense, both are categories of objects that contain an aura, real or imagined, that trigger powerful responses. They become, if you will, the metaphorical shoes inside of which we are invited to walk and for a moment attain a sense of intimacy with the unreachable.

Dedicated to Tamara Díaz Bringas (1973-2022)