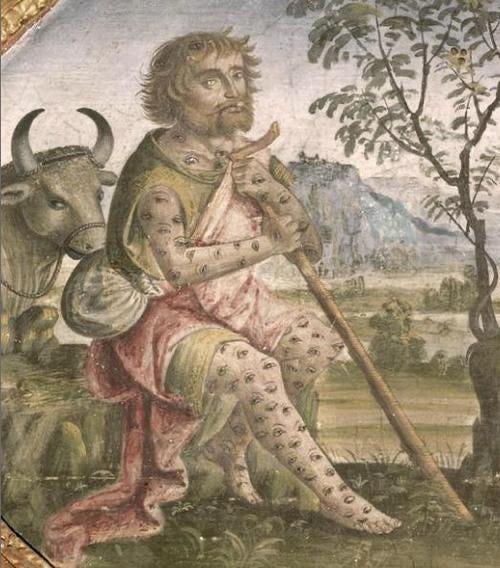

Bernardino Pinturicchio, Mercury, Argus, and Io, 1492-95, fresco (fragment), Sala dei Santi, Appartamento Borgia, Vatican

Those of us who teach art in academic settings tirelessly repeat the mantra: “do your research.” Artistic research is often daunting for students because of the enormity of historical references out there (and because students generally don’t like to do research), but our role as instructors is to show them that their work will be ultimately valued in terms of how it shows awareness of, and advances, the dialogue around any topic or technique; it also is a necessary tool in a profession that often falls prey to the mythology of the original genius. Lack of research, unless one is a brilliant outsider artist, often shows in the work and can look like mere amateur hubris.

But for all this talk of research there are certain guiding principles of it that often remain unspoken. While there are several, I will only outline four of them here.

The first one requires an anecdote. A few days ago, I ran into a curator friend and ex-colleague of mine who I had not seen since the pandemic started. I worked alongside him for many years and during that period I had the opportunity to sit with him at a weekly meeting where very elite curatorial discussions used to take place (an elite group within an elite museum). As we started a conversation to catch up, he gradually reverted to the kind of talk that used to go on (and ostensibly still goes on) at those curatorial meetings, which I had forgotten about. Will I go check out Documenta 15? He just came back from the opening of the Venice Biennial, did I go? Will I go this year to Art Basel? Might I do the “grand tour” (as some art world insiders call it) and see all three shows in one European swing? Did I see the catalog about X or Y exhibition, or that X or Y curator did this or that project? Did I read this recent review written by Z? As I tried to field this barrage of questions, I started feeling the heightened awareness (and accompanying anxiety) traditionally described as FOMO— being hopelessly out of the loop regarding international exhibition news, currently missing a thousand critical things happening right now.

This led me to my realization that the first golden rule around research is in fact a banal truth: research requires resources. In other words, to attend Documenta, Venice, Basel, visit the key biennials happening at any given moment and acquire and read their corresponding exhibition catalogues one needs two essential things: time, and a budget (something that, when you are a full-time curator at a major museum you usually have access to). When you are an individual artist, and even when you live in an art capital where a lot of those important events come your way, you still need to try to see the exhibitions that might be game changers in the conversation. I can immediately hear objections from those who might say that it is not a requirement, not even an essential necessity, for any artist to attend events like these. Yet two facts remain: first, access to information and being up to date is a form of currency, aside from a way to knowing what is currently dominating in the art discourse. The second is that the art world is like a party: if you just arrived you might not know what is going on in the conversation and might have a hard time inserting yourself in it. This is why artists who are familiar faces of the biennial circuit already have a built-in advantage in their already being part of that community, which becomes a self-enforcing mechanism: those who are more present at those events (even if they are not included in the exhibitions) are more likely to become engaged in the future under that or similar contexts. Some art foundations recognize the need of artists to use funds for research, and art residencies provide some of that support (primarily in terms of time and space). But research, unless it comes with the promise of a product, is generally not of great appeal to funders, so as artists we need to contend with that reality.

Now to the second rule of artistic research: artistic research requires, for lack of a better term, dialogic fieldwork. It is generally implied that research is a bookish enterprise consisting in spending time in archives, doing reading and close-looking — all of which are true to a certain extent. However, research is also conducted— and I would add, must also be conducted— through socializing and in conversations (and sometimes more formally, conducting interviews) with others— a principle that is common in interactive learning methodologies used in anthropology and ethnography. I have learned this in my long-distance relationship with the Mexican art scene (given that I have not lived in Mexico for decades). Like almost everyone else in Mexico I follow the news of exhibitions and various debates through social media and other publications about what happens there, but it is only when I am physically present where I can truly debrief with others (artists, curators, and other friends) to really get the back story of various issues, understand the socio-cultural or political context of some events, and sometimes—let’s face it— even get the vital gossip around certain subjects that would be impossible to capture virtually or in the public sphere. This granular understanding of the art scene and its concerns becomes immensely helpful in producing work that might meaningfully engage with the local context.

The third rule of research is that, like in the case of healthy foods or diets, one can have too much of a good thing. The way it translates into artistic research is twofold: one, the case where compiling a sea of references can result in paralysis, and the one where research takes over a creative practice to turn into an academic one. In both instances we can become victims of our own over-research. After the exchange with my curator friend, I later thought about why I could never be a curator – let alone operate at the level of my friend: as part of his job, he absolutely needs to be on top of every single thing that happens in contemporary art, and be an art-researcher version of Argus Panoptes, the hundred-eyed giant in Greek mythology and servant of Hera, whose main task was to be the guardian of the nymph Io (from his name the term “Panoptikon” originates). Argus meets his end when Hermes surprisingly hits him with a stone the moment he falls asleep. The morale of the story in this myth is that one can never close their eyes— which can be interpreted as a metaphorical cautionary tale for the curatorial practice: the moment you don’t pay attention to what is happening out there, you will also lose your edge and, probably, your relevance.

In the case of the artist, while being aware of what is happening in the artistic practice is key, being on top of absolutely every exhibition, publication and event is impossible, and might in fact become counterproductive: at least inasmuch this desire and ability to explore and learn about the goings on in the art world is not balanced with a rigorous studio practice where one is able to also focus on one’s own work. I suspect (but can’t prove) that going to many evens and meetings may sometimes be an unconscious way to avoid the studio while justifying our need to remain involved professionally in the field. This is best exemplified in the artist (we all know at least one) who spends more time attending openings and art events than making their own work, to the detriment of the latter. The other version of this lopsided balance between research and practice occurs with those artists who are very versed in theory. On various occasions, as visiting artist in studio programs, I have encountered highly intellectual and erudite artists who can theorize you into a corner, but when one sees their work, it either looks like they are making children’s book illustrations of their (or other theorists) ideas or that they simply have not properly developed and mastered the required technical and visual skills to make a compelling image.

Last, but not least, I have learned the importance of identifying the dead end of a research process. There are times where stars appear aligned (say, an invitation to develop a project at a wonderful institution with resources) and there is a promising opportunity and resources to develop particular research question only to conclude that no meaningful progress or productive result can be derived from one’s efforts (due to lack of inspiration, or to the inability to find an idea with “legs”, or due to misalignment of interests between oneself and one’s hosts or funders). Those who are stubborn when faced with no good results often plow along, which might eventually be worse than accepting defeat. Nonetheless —and here end with an optimist note— there is always silver lining to failed research: you might discover other things along the way; you might pilot working approaches that you would have not attempted otherwise and which you can use in the future. As the myth of Argus shows, even a creature with a hundred eyes can be blindsided, but by diversifying our approaches to learning, humbly understanding our limits, and applying pragmatism in the use of our available resources we might be able to survive the unexpected blow of Hermes.

I always love your writing even when I sometimes disagree but altho all you write is true in an ideal world, what is left out are questions of access and privilege. Relatively few people who identify as artists can both attend the "party" and have adequate studio time. In most cases that's a question of access to time and money. Increasingly, particularly in this country, that's restricted to a class of the privileged that has nothing to do with talent or will to do conscientious research.

Speaking as an artist who was pushed out of NYC by costs, couldn't get a regular teaching job, has health and age disabilities, I resist this prescription for research that conflates historical success, visiiblity and material stability with careerist value. When I was a young artist in NYC, everything you describe was available: cheap housing and a job were a given making everything else possible. That is no longer true. I can't help being grateful for the internet. It is an inadequate platform for research and one that wasn't mentioned. And my experience of limitation is a pale version of what single mothers for example face- a group that will undoubtedly explode after the Row vs Wade battle is won by fascist fanatics.

The decentralization of the artworld redefines how any of us can and must do research. What is within walking distance for example in Manhattan during prime time is just not an option for many, many terrific artists and THAT's a problem. I think the emphasis should be less on what the privileged must do to refine their practice and perhaps more, on how we can make access more equitable, to include value that goes beyond the flavor of the day amongst the elite.

The artworld always reflects the greater culture. In this case, the criteria to engage in the artworld you have described is a gross exaggeration of the grotesque privilege and entitlement of a small group we see reflected in the tragic income disparities that are escalating worldwide. My suggestion is that you take into account how the present culture of privilege has become an ever more insurmountable gatekeeper for artists to participate in the research you describe over the past fifty years. In fact, without that caveat, I think research can only reinforce the status quo that we as artists are always tasked to question.

Muy lindo ensayo Pablo!