Art's Overton Window

Political framing approaches as applied to the art discourse

Fresh Widows (after Duchamp)

If you are anything like me, you probably are deeply concerned with the future of democracy in the United States and the increasing propensity of the hard-right toward violence and authoritarianism. In texts and interviews on the topic, political analysts and pundits (liberal and conservative alike) almost universally acknowledge the fact that Donald Trump’s candidacy and the emergence of Trumpism had the characteristic of completely upending the political status quo, creating a climate where dog-whistle messages would no longer need to be said quietly. When you absorb all that commentary over a period of time like me, you start noticing a series of recurrent terms: these include “permission structure” (“A Permission Structure provides an emotional and psychological justification that allows someone to change deeply held beliefs and/or behaviors while importantly retaining their pride and integrity.”) “Landscape amnesia” (referring to how we accept abnormal changes as long as they are gradual), and “Opinion Corridor” (“a metaphor for the limits of what is commonly acceptable to debate.”). All these are interconnected terms. The term that has interested me more of the group is the Overton Window.

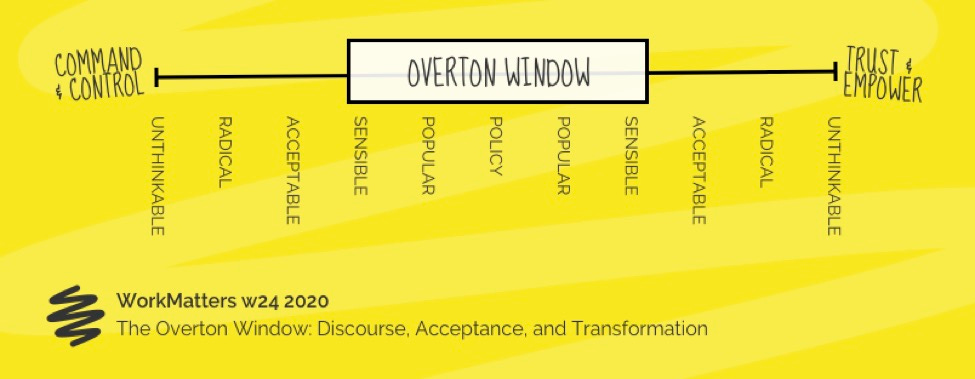

The Overton Window, also known as the window of discourse, was a concept introduced by Joseph P. Overton (1960-2003), who was vice president of the Makinac Center for Public Policy, an influential conservative think tank. In order to explain political messaging, Overton made a cardboard slider model that would show the range of acceptable policies that the public would allow, going from no government involvement to complete government control. While according to the model the extremes are implausible they provide a middle ground within which one can craft a political discourse that voters would support. The shift on how the Overton Window moves on various issues can be unpredictable, for instance, after the public backlash after the Supreme Court’s overturning on Roe vs. Wade some Republican politicians found that they needed to moderate their positions on abortion, and even then there is evidence that the issue helped the Democrats in the midterms. The Overton window had shifted to the degree that the most extreme pro-life views (even in the case of rape and incest) became more politically unacceptable than before.

The question that interests me is how the Overton Window principle applies to the art discourse. I have touched on related topics in past columns, in particular to my interview with Hans Haacke on his famous 1971 censored work Shapolski et al. and a cursory overview of taboo subjects in the art world. My interest in the subject today pertains less to those topics that are untouchable and more about how the “window of acceptability” of a particular artistic moment, if/and once it is determined, helps us gain an understanding of the cultural zeitgeist.

The question, of course, depends enormously on historical proximity. It is fairly easy to figure out, for instance, what was verboten as a subject in past historical periods, and how the artworks and artists who crossed the line of acceptability helped redefine paradigms, either by showing what would be possible or by revealing what were the fault lines that indeed were not worth or crossing.

Contemporary art history is full of works by artists who have walked the fine line of legality, wherein the visual evidence is provided but always with a certain degree of ambiguity that would allow the artists to claim the work to be fiction it came to be the case. I am thinking of the 1997 provocative video/installation by Miguel Calderón and Yoshua Okón (at the time young emerging artists who had recently launched the alternative space La Panadería in Mexico City) titled “A propósito” (On Purpose), showing 119 stereos they had obtained in a stolen goods market next to one more stereo that the artists claimed to have stolen themselves, showing the act of smashing the window of a car and taking the stereo from the dashboard. I asked Okón if they had any legal troubles after exhibiting the piece. “The intention was to show it as what it was, a true theft. And it was an important aspect of the work was the fact that the rest of the stereos were bought in a market where it was well known that they were stolen.”

Yoshua Okón and Miguel Calderón, "A propósito",1997. Video installation. Image courtesy of Yoshua Okón.

Within those countless examples of artists who crossed the line creating controversial works, there are those that touch the extremes: Cildo Meireles’ Tiradentes: Totem-Monumento Ao Preso Político from 1970, a piece where he tied 10 live chickens and set them on fire as an act of protest against the military dictatorship in Brazil. The following year, Chris Burden had a friend shooting him in the arm with a .22 caliber rifle.

Looking at those works, consider what sort of reception these would have if they were made today, and the response that they would receive within the current political context. I don’t have the space here to make an ethical study on specific works, but mainly want to point out that every period has an Overton window that is important to understand and, when transposed to a different time period, it might be seen in a completely different light

This transposition is something that artists have to confront when their own artistic legacy strikes back at them. In the case of Chris Burden, in 2005 a student in his UCLA class brought a gun to class and did a Russian roulette performance. Both Burden and Nancy Rubins, who were married at the time and both taught there, submitted their retirement paperwork shortly after the incident. Granted, it is not the same to bring a gun to class than to present an art work at a gallery involving a gun. Still, the episode highlighted among some of us the question of whether the extremes of conceptual and performance works of the 1970s still made sense today.

The questions we have to confront as contemporary viewers of works like these is how to reconcile our contemporary sense of ethics, justice and morality in relation to that work. The critical consensus is that we might be able to understand it, but inasmuch as the work exists in the present, we can’t condone it or justify its characteristics simply because it was made in the past.

I decided to approach an artist who I consider a leading practitioner of testing the limits of the Overton window in art: Andrea Fraser. Fraser’s talent has consistently been her ability to detect the structures of power and, by inhabiting them making them visible to us. I wanted her to tell me what her Overton theory, if you will, might be. I asked her on the subject of acceptability in an art work and how she personally considers it.

“I don’t think I could ever say that there are any topics that are categorically unacceptable for an artwork. There are many art works that I personally find unacceptable, but I think that is never because of subject matter exclusively, but because of how that subject matter is engaged. But I would never generalize my criteria in making that judgement. “Unacceptable” always implies unacceptable to someone: some position or perspective of relative judgement that is always be very specific in my sense of the term. Counterproductive is a similarly relative to how productive is defined.

If you are asking about my personal criteria in this regard I would say that, there is very little art that I find acceptable according to my personal criteria. But if what you mean by unacceptable is art that I think should not exist at all, the art that falls into that category for me is art that is gratuitously provocative and that seems to have no compelling reason to exist other than that of securing attention. Another category that is harder to define is art that uses its subject matter or its audience as containers for toxic projections of aggression, hate, guilt, and shame. What makes that kind of art unacceptable to me are not those affects, impulses, or attributes themselves but the degree to which artists split them off, disown them, and puts them into others, whether represented others or audiences.”

Andrea’s response made me think about the difficulties of establishing a stable Overton window of discourse in art. Then again, this is the problem that art criticism contends on a daily basis. We can only have very concrete responses by specific artists, and it could be argued that every artwork made establishes (or pushes) the Overton window of discourse.

But going beyond categories that are open to interpretive debate (around ethical issues for instance), legal/practical boundaries are often the most clear ones that all of us who make art or engaged in curating or producing have to confront. This brings up an anecdote in my mind.

In November 2004, the last exhibition I worked on during my 7-year tenure at the Guggenheim museum was The Aztec Empire (I ended up being recruited to be the voice of the acoustic guide since I was the only one on staff who could pronounce names like Coyoxaulqui and Huitzilopochtli).

As part of the exhibition’s public programming, I was able to curate a performance by Guillermo Gómez-Peña, de legendary “post-Mexican” (as he calls himself) performance artist, writer and radical. I have known Guillermo since the early 90s in Chicago and like many in his orbit I would often be absorbed into his many performance interventions. In this instance, I was able to bring him to the Guggenheim to deliver some of his famous monologues that concern Mexican identity, borders, transculturality, and an overall cosmogony where Chicano culture, the underground and the pre-Columbian universe often meet.

Gómez-Peña, wearing a black skirt, high heels and pre-Columbian gear, presented a performance-monologue titled “From Aztec to High Tech”, full of his energetic and characteristic wit, inventiveness and poetic border aesthetics. At some point in what appeared to be a spur-of the moment action, he pulled out a cigarette and started smoking while speaking.

Almost immediately the head of security got a hold of me in the back of the auditorium. He was accompanied by three other angry guards. “He has to turn off that cigarette!” he told me sternly. “but it is part of the performance”, I said. “He has to turn it off!”, he said again, panicked. “the smoke alarm will go off and we will have to evacuate the entire auditorium!”

So I had to run backstage to try to make signals to Guillermo from the side to indicate that he needed to turn off that cigarette. They were the two longest minutes of my life. At first he didn’t appear to see me, but he later appeared to notice my signals and put out his cigarette. I breathed a sigh of relief.

But a minute or so later, understanding what the problem was, Guillermo turned to me again and pulled out a joint this time, looking at me in a mischievous way.

“I am sorry, Pablito.”

Everything done in the name of art, the Overton window be damned.

Great!!!