Black Bears in Black Mountain: Postcard from Appalachia

Friday was my birthday, and as many of you know, Dannielle and I have an elaborate annual ritual: each year, on the day of each other’s birthday we create a series of interlocking surprise experiences for one another. I wrote about this tradition last year. This time, her surprise for me was to bring me to Asheville, North Carolina. We spent part of the day visiting the studio of Phil Sanders, one of the most skilled and knowledgeable master printmakers in the country. He walked us through a range of remarkable editions he’s recently produced in collaboration with major contemporary artists across the U.S. Toward the end of our visit, the conversation briefly turned to the current political moment. He said something that stuck with me—something like: “We can’t know the importance of this moment because we’re living through it. Others will come later to make sense of it. All we can do now is pursue wild creativity.”

Earlier that day we had met Connie Regan-Blake, a nationally recognized storyteller who shared a traditional Appalachian folk tale passed down from her mentor, Ray Hicks. She lives deep in the mountains, up a steep and winding road lined with fallen trees—stark reminders of the devastation left behind by Hurricane Helene last year.

As we were leaving the area, driving down the highway, we encountered a group of black bears in the process of crossing— a mama and her cubs — a scene so unusual that even the locals were surprised, let alone us Brooklynites.

Of course, the literary component couldn’t be left out of this birthday celebration, and Dannielle arranged for a visit to the historic boyhood home of Thomas Wolfe, the author of Look Homeward, Angel and one of the most influential American writers of the autobiographical novel, despite his untimely death at 38. Wolfe, who at some point lived in the Chelsea Hotel and frequently traveled to Europe, often wrote with deep nostalgia for his past, even as he famously penned the words, “You can’t go home again.”

In conversation with the museum staff, when we mentioned that we hailed from Brooklyn, one of the guides suggested we read Wolfe’s short story “Only the Dead Know Brooklyn”. I took his advice and read it today. The story centers on a subway encounter between a Brooklyn native (the narrator) and an enigmatic wanderer who describes his experience combing the borough with a map, particularly his time walking around Red Hook (our neighborhood), where he witnesses a brawl in a bar. The narrator is horrified and warns him, “Jesus! Red Hook!” telling him to “stay away from deh.”

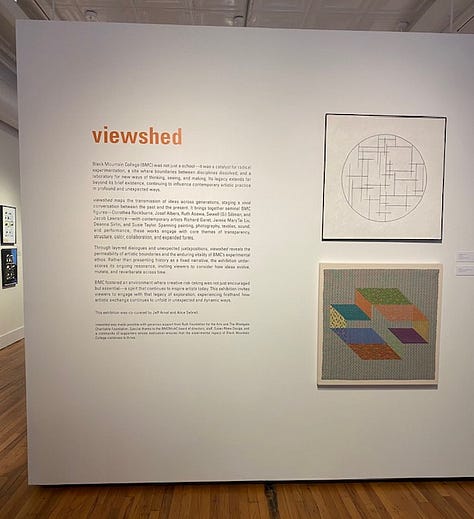

What truly motivated Dannielle’s decision to bring me to Asheville was the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, a place that has always held deep significance for me. For those of us passionate about multidisciplinary art practices and pedagogy, Black Mountain is something of a Mecca—an evocative, almost magical word. It’s shorthand for the fusion of community, learning, and radical experimentation. In this political moment, reflecting on the utopian ideals of Black Mountain in the postwar era feels especially inspiring. Though its existence was brief (Black Mountain was open for 24 years—actually a decade longer than the Bauhaus), its impact on art history was profound and lasting.

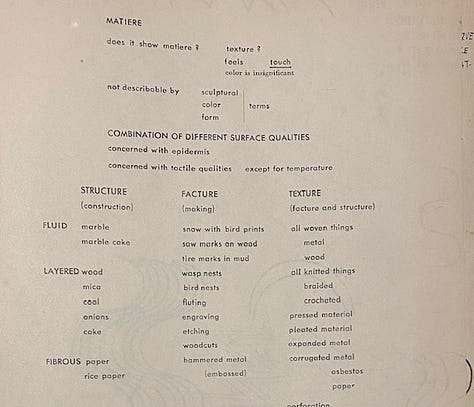

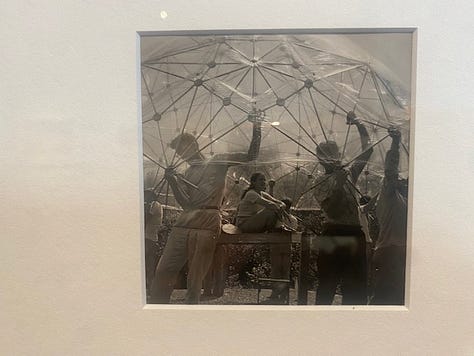

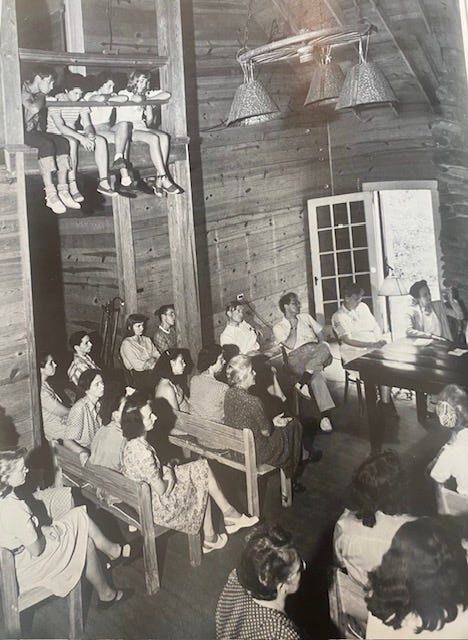

As I looked at photos of students attending summer lectures, building one of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, or collaborating in the creation of a unique artistic community, I felt a deep kinship. I recognized a spiritual lineage that would later manifest in social practice half a century later, as Gloria Sutton discusses in her essay on the topic. In that sense, visiting the Black Mountain Museum felt like reconnecting with lost relatives.

We head back to Brooklyn tomorrow, and tonight I’m reflecting on all that we experienced today. The encapsulating image that keeps coming to mind is that of the black bears—not just as a chance encounter with the wild, but a liminal symbol of nature asserting itself in its raw, untamed form. In many ways, the artists drawn to Black Mountain College were similarly ready to embrace the unpredictable, the unknown. The rawness of the experience was something Albers acknowledged in a letter to Jacob Lawrence, where he invited Lawrence to teach at Black Mountain, cautioning him about the region's racism and inhospitable environment, but also warning him that the financial rewards would be few (and suggesting: “bring whisky”). Yet, despite these challenges, it was that very embrace of creative wilderness that led to some of the most groundbreaking art of the 1950s and set the stage for much of the experimental art that would follow in the latter half of the century.

A year older now, I return to the now more gentrified and boring Red Hook, but now with the reminder of that wild experimentation that once happened here. Black Mountain may be in the past, and as Wolfe said, we can’t go home again. But when it comes to pursuing that wilderness of creativity, neither should we, nor can we, stay away from the— at least while we are still alive.