During the 11-week Kellogg’s strike last year, which ended on December 21, 2021 with a contract resolution for 1,400 workers, production stopped in four plants in Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania and Tennessee, resulting in a shortage of Kellogg’s cereals in grocery stores across the United States.

But the shortage might also have laid bare a trade secret. A few days ago, Charles King, a designer friend of mine who lives in upstate New York, pointed out on Facebook that at his neighborhood’s Wegmans supermarket, which sells the store’s generic version of Rice Crispies (Crispy Rice) the item was also absent from the shelves. When he inquired with the employee about this, he explained that Kellogg’s also makes the generic brand of Crispy Rice for Wegmans, which is basically the same product except in a different box with the store label and a cheaper price—thus the explanation of why that product was also unavailable.

I have never given much thought to generic brands, nor do I suspect most of us spend much time worrying about where those products come from. While I am unable to confirm the exact provenance of Wegmans’ Crispy Rice cereal, it is known that in many cases generic brands are manufactured by the same companies that produce name brands. Take Trader Joe’s as an example. As the food publication Eater has reported, “As a private brand, the California-based Trader Joe’s orders most of its products from third-party manufacturers (including giants like PepsiCo. and Snyder’s-Lance), which agree to sell some of their items under the Trader Joe’s label. Many of these brands sell the same or similar products under their own names for a higher price. The catch is that Trader Joe’s and its suppliers all but swear to keep the agreement secret.” The original supplier’s identity can be sometimes unmasked when companies face federal recall orders. As an example, the Eater report offers this: “In March 2016, Wonderful Pistachios & Almonds LLC, which produces the Wonderful Pistachio brand, issued a recall for three types of pistachios sold at Trader Joe’s, including the dry-roasted and salted variety. A year prior, the makers of Tribe hummus recalled a brand of Trader Joe’s tahini-free hummus because it may have contained sesame seeds. And Naked Juice, the PepsiCo. subsidiary and leader in bottled smoothies, supplied the grocer with protein fruit smoothies, recalling them in 2008 over yeast and lactic acid bacteria.”

Of course, generic brands exist all over the world. In Mexico, for example, the market of store-brand pharmaceutical products has quadrupled in size over the last 8 years, with 25 million products sold.

Speaking of Mexico, when I heard the Crispy Rice story I had a flashback to a anecdote connected to the early years of Zona Maco, the contemporary art fair in Mexico City. During one of the editions of the fair and shortly after the vernissage, a group of art students from La Esmeralda (the National School of Visual Arts) set up camp on the street right outside the art fair, selling replicas that they had quickly made of some of the artworks one could see inside, although at bargain-basement prices, as some kind of conceptual mischief. I inquired about this to one of the Mexican artists whose work was “replicated” at the time, Eduardo Abaroa. He recalls: “I heard they made a pirate copy of a Pedro Reyes video and they made a poor version of one of my paintings. A collector actually purchased it and gave it to [the dealer] José Kuri, who then gifted it to me. I think I have it laying somewhere.” (*)

All of which made me think on how and why “genericism” manifests in art making.

At a first glance, one would think that we can’t really have a functional “generics” market in art because, as we well know, market value is largely dependent of the worth of the name of the artist so there would be no real financial incentive for an artist to produce the same product for others unless it were a forgery, and the line between copy and forgery can be tenuous. However, a forged artwork is not a generic artwork, if we were to apply the principle that the product is an acknowledged imitation of the original. Beyond that, genericism in art can manifest in several other ways.

A possible art historical study of the root of genericism can start with looking at the artist workshops of the Renaissance. There we can find a case of inverted proto-genericism where instead of the product without the name of the brand one could acquire the brand without the exact “product” (i.e. a work that may or may not have been made by the actual hand of the artist). The development of the large workshop model is generally attributed to Perugino, who, as art historian Sylvia Ferino writes, “developed the traditional Italian workshop into a highly organized artistic enterprise for the large scale production of individually commissioned paintings.” Many of his apprentices became artists in their own right, most famously Raphael. Over his life, Perugino took over 200 commissions (many the equivalent of site-specific projects today) which would have been impossible for him to complete single-handedly. But his enormous output could only be satisfied by developing formulaic approaches and repetitive motifs and compositions produced by an army of studio assistants, which led to criticism of his work: Michelangelo famously once derided him as a “goffo nell’arte” (“bungler in art”). In any case, and despite the later decline of his reputation, Perugino’s workshop model was followed by countless artists over the centuries and in a way laid the foundation for the contemporary artist studio business models of today. What could be argued in fitting this example within the “generic” category is that at least some who commissioned works must have known that the artist was not personally (or at least wholly personally) making the pieces— in many cases they were acquiring a quality-controlled, artist-approved product at best. But for all practical purposes, and despite its signature, many of these pieces likely were/are “generic” Peruginos.

A closer case of genericism can be found in imitations of works of prominent artists, the most interesting in my view being the one of Fernando Botero, whose work seems irresistible to copyists and forgers. Most interesting to me is the vast amount of copies of his paintings which are widely available in various places in Colombia (back in 2017 I purchased one of those “Boteros” in downtown Cartagena, for $10) and how this practice has practically turned now into a popular art form.

A “Botero” acquired in downtown Cartagena in 2017

To better understand this phenomenon, I contacted Christian Padilla, one of the leading Botero scholars and an authority on his early period.

“Botero is the most forged artist in Colombia, so the line between imitation, copy and forgery is very thin, depending how you look at it”, says Padilla. The examples run the gamut from homages and derivative works to outright forgery. He cites the extreme case of artist Arcadio González, who in the 70s/80s shamelessly imitated Botero and even had the audacity to claim that Botero was the one who imitated him. “Then there is the case of the copyists”, Padilla adds. “I would not say that they are part of the art market, but rather their activity is more linked to tourism, mostly limited to the historic downtown areas of Cartagena, Medellín or Bogotá. In the case of this commercial practice, neither the art market nor Botero himself see it as a threat. On the contrary, Botero feels very honored that his work had been appropriated in this popular form and, furthermore, he would not even be able to control how the acknowledgment of his work in Colombia goes beyond his name, like a brand.”

A Botero imitation (image courtesy of Christian Padilla)

Nonetheless, a side effect of this phenomenon, Padilla points out, is that sometimes these imitations make it into collector’s homes and either due to ignorance or malice some start selling them as authentic, in the worst cases with sellers even falsifying authenticity certificates. Padilla: “given that I have spent a decade studying Botero’s early production, I am very familiar with this phenomenon and I can tell you that I probably have the largest archive of Botero forgeries in the world.” Many museums, dealers and collectors internationally regularly contact Padilla to authenticate undocumented works, “which in 90% of the cases are forgeries.”

Following the principles of genericism (just articulated in the last few paragraphs) as something more aligned with appropriation art, who then would be the greatest exponent of that practice? The list is very long, but I would argue that it should likely start with Elaine Sturtevant, whose inexact replicas of major 20th century artists explored, in her own words, “the understructure of art.”

Elaine Sturtevant, Warhol Diptych. 1973/2004. Synthetic polymer screenprint and acrylic on canvas. Pinault Collection.

The list of significant artists and projects related to this topic is truly endless. But to cite yet one memorable case of genericism toying with forgery that is quite conceptually dizzying (although in a playful and self-referential way) there is a project by the renowned Catalan photographer Joan Fontcuberta worth remembering. Fontcuberta became famous in the late 1980s and early 90s for making projects that played with falsified documentation, problematizing the notion of photography being a source of “truth” — a precursor to the “fake news” era. As part of one exhibition project in 1995 titled The End(s) of the Museum, Fontcuberta created a “historic” exhibition of major modernist Spanish painters who ostensibly experimented at some point with photography, including Miró, Picasso and Dalí (none of these artists ever made a body of work in that medium in real life, but Fontcuberta managed to deftly imitate the aesthetic of each artist, translating it into photography so the works could plausibly be seen as theirs).

One of Fontcuberta’s false Miró’s photographs: “Preparatory Sketch for Paisatge de Sant Anton, 1961” Gouache on gelatin silver print

In the case of Antoni Tàpies, whose work was also included in the exhibition, there was yet another twist to Fontcuberta’s naughty scheme: viewers who were familiar with Fontcuberta’s work assumed that he had also forged Tàpies’ photographs, while in fact Tàpies himself had willingly conspired in collaborating with Fontcuberta and, in a way, “self-falsify” his own works. In this case, Tàpies, in a Kellogg’s-style move, had secretly agreed to make a “generic” product (a supposedly fake piece by Fontcuberta), when in reality the product was authentic. So in this case it was an undercover fake that was in fact original, resulting in a Fontcuberta “store brand” product.

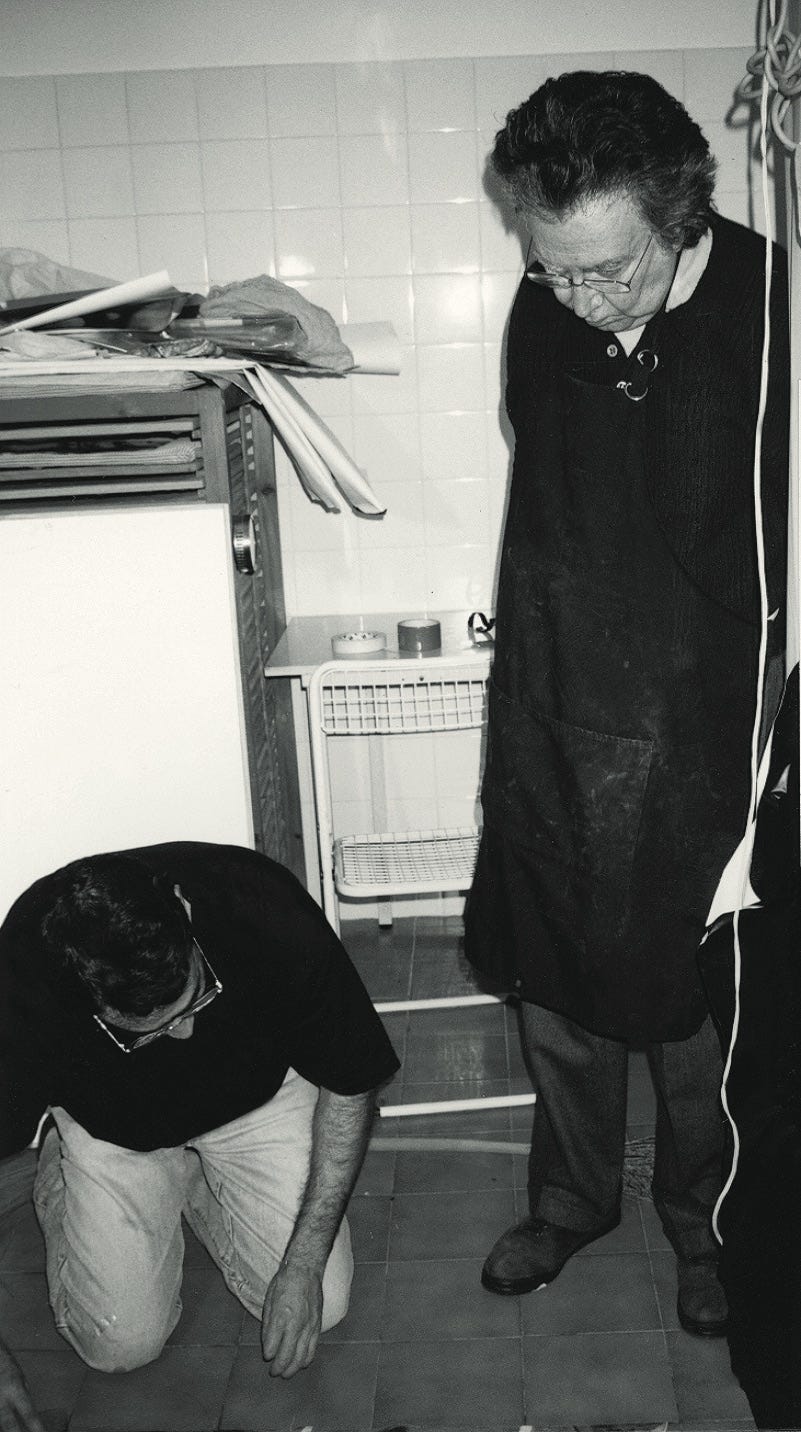

Fontcuberta and Tàpies at work, c. 1994; the series exhibited at MUA Alicante. (Photos courtesy of the artist)

The generic production scheme was so successful that the true authorship of some of these works was opaque even to Tàpies himself. When I recently asked Fontcuberta about the collaboration, he told me: “we were working one day together, making photograms and chemigrams, all very dirty and matteristic. When Tàpies left, I continued with the same dynamic and my results turned out to be more “Tàpies” than Tàpies himself. When we did the exhibition, Tàpies came to the opening and was unable to recognize the piece that he had made in my studio apart from the ones I had made later. It definitely was a way to desacralize the authority of authorship and style.”

Maybe one day, if we ever become less fixated on artist names and in the sacred value of authorship, we might be able to embrace the financial benefit of generic artistic brands in the avant-garde experimental tradition of Wegmans and Trader Joe’s.

(*) After publication of this column, several have also pointed out to me Copystand, a wonderful conceptual project by artist Stephanie Syjuco, described as follows: “A parasitic project, COPYSTAND was a five day performative counterfeiting event held within its own gallery booth at the Frieze Art Fair, London. During the week, a cadre of three to five artists in a Production Area re-created artworks found in other booths and displayed them in a formal Gallery Area. All works were available for purchase at a mere fraction of the cost of the originals. A final liquidation sale happened on the last day, with massive discounts and resulting in sold-out inventory.”