Buenos Aires the Memorious

Monuments, cultural ghosts and other forms of recall and forgetting (letter from Argentina)

(Warning: this note starts with darkness, but I promise it will end in levity.)

Last week I was in Buenos Aires to open an exhibition. I had not returned to Buenos Aires in quite a long time and being back made me realize the very strong affinities I have with this city.

For starters, Argentina is a country with a deep and complex cultural relationship to memory. The subject of longing and oblivion is an ever present motif in the classic Tango repertoire: Caminito (“Caminito que el tiempo ha borrado…”), La copa del olvido, Adiós muchachos (“Acuden a mi mente recuerdos de otros tiempos/ De los buenos momentos que antaño disfruté,”), etc. The rituals and language around remembrance are so much part of Argentinian culture that it only makes sense that one of its native writers, Jorge Luis Borges, would have invented the literary character of Funes, from the short story Funes el memorioso (Funes the Memorious), about a man who is unable to forget anything. His story is a delectable anti-sentimental parable on the utopia of total preservation of memory, showing us that the ability to remember every single thing in our lives is in fact no blessing, yet perhaps —as this city proves— necessary.

Because Argentina, like most other countries, does have to negotiate and come to terms with its own past, both distant and recent. Nowhere it this clearer than with the slogan Nunca más, which was the title of the 1984 report of the National Commission of the Disappearance of Persons documenting the human rights violations of the military dictatorship in Argentina between 1976 and 1983. Currently at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes there is a comprehensive retrospective of the work of León Ferrari, showing many of his highly confrontational works critical of the military dictatorship, as well as the Catholic church of which the artist was also a virulent and powerful critic. The powerful show is an interesting marker of continuity, memory and also of how of how political art makes one come to terms with one’s history (the Oscar-nominated film Argentina, 1985 was very present in my mind throughout my entire time there).

It is also interesting to see how the themes touched by Ferrari in his work have also undergone a public assimilation of sorts. In 2004, the curator Andrea Giunta organized a first major retrospective of Ferrari (still during his lifetime) at the Centro Cultural Recoleta, which provoked an irate reaction from the Catholic church and the hard right; Ferrari and his family endured death threats throughout the duration of the show. Speaking to the curators of the current show at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes they shared that this time, perhaps because of the passage of the years, there have not been death threats and the reception has been largely positive.

(Of course, one can never entirely dispense with the past. Just this past Tuesday, the news came out that a plane used by the Argentinian dictatorship to carry out the infamous “death flights” during the Dirty War (used to throw prisoners of war from the planes into the open sea) had just been located in the US and is now being returned to Argentina.)

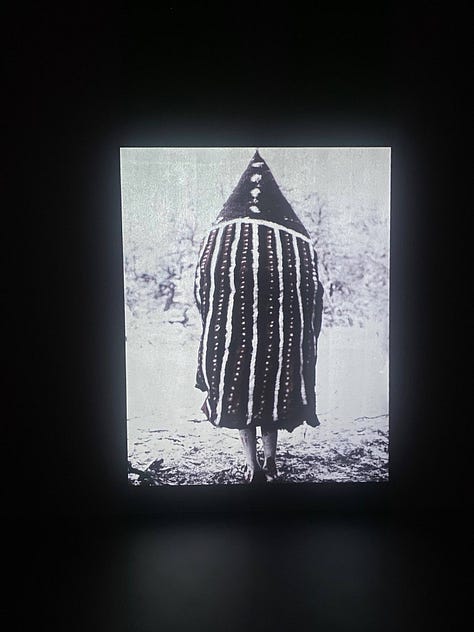

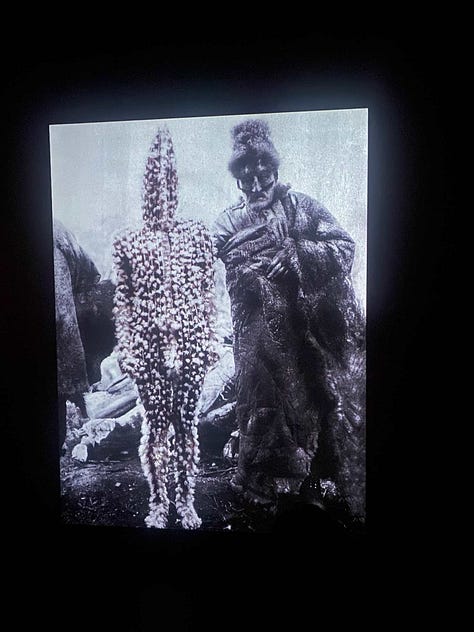

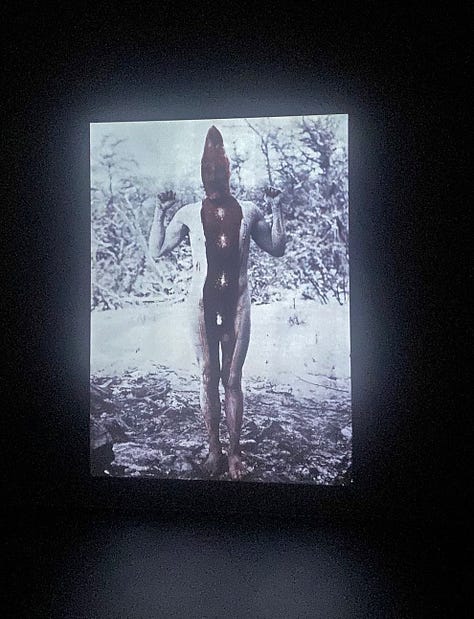

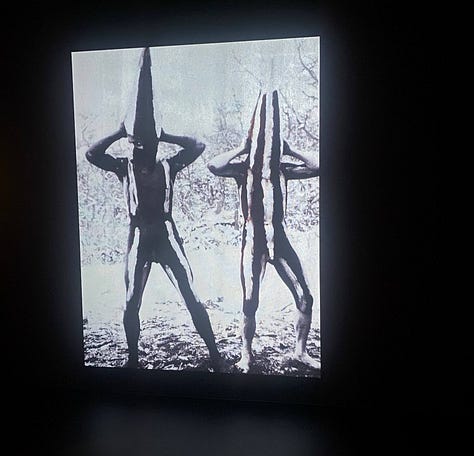

Things got even darker, literally and metaphorically, when I visited the sprawling and ambitious exhibition A 18 minutos del sol, curated by Javier Villa y Marcos Krämer at the Museo de Arte Moderno (as an aside, the museum is now under the expert leadership of Victoria Noorthoorn, who I met shortly after I had arrived in New York in the 1990s and whose Master thesis, to the point of this note, was precisely titled “The Challenge Of Memory”). The show reflects on the subject of astronomical and scientific observation as material for modern and contemporary art practice. The exhibition opens in a large, darkened room that pays tribute to the ancestral knowledge of the sky of Andean cultures. The gallery is divided in four sections that correspond to the Patagonia, the Littoral, the Highlands and the Lowlands of Northwest Argentina. Embedded forever in my mind will be a slide show of photographs made by the Austrian priest and ethnologist Martin Gusinde of an initiation ritual for male adolescents known as Haim, performed by the Selk’nam, an indigenous people who lived in the Southern Patagonia/Tierra del Fuego region of Argentina and Chile, and who were driven to extinction as a result of the expansion of gold mining and farming. The Selk’nam genocide took place toward the end of the 19th century; by the time Gusinde took these photographs in 1923, there were only less than 300 Selk’nam left; the last full-bloodied Selk’nam died in 1974.

The story of the Western exploitation and extinction of the Selk’nam is narrated in a novel by the Argentinian writer Carlos Gamerro, La jaula de los Onas (The Cage of the Onas), a work inspired in an episode in the World’s Exposition in Paris in 1889 where nine Selk’nam where exhibited in a cage to the European public. Gamerro, who I was lucky to speak with regarding the tragic story of this culture, has described his work as a “love letter to Patagonia” as well as a work that, more than a reflection on the Western gaze toward Argentina, “is about the gaze of the Argentinians toward themselves through what they imagined the Western gaze to be.”

As a result of a lifetime of working in the world of image-making one sometimes feels as if one has seen it all; however, I was truly haunted by the Haim ritual photographs in ways that I still can’t completely articulate. As they are shown in a museum, a visitor who might not read the wall label could easily construe them as some form of ritualistic performance art when in fact they originate from deep and ancestral religious beliefs, giving them a gravity that no contemporary performance art piece could possibly have. Last but not least, the fact that these are images of a long-gone culture whose erasure was authored by modern civilization makes the slide show feel more of a phantasmagoric visual requiem.

But this phantasmagoria also exists in modern, urban Argentinian versions and its contemporary art. In one of the various art spaces I visited I saw the work of the emerging artist Alfredo Dufour in the artist-run gallery Constitución, located in a historic building in the touristic area of La Boca. Dufour’s show, titled Vendo Miedo (I Sell Fear), included a handmade coffin (Dufour is a prop-maker for theater productions, and he takes advantage of his manufacturing skills), a mannequin with the face of Marilyn Manson carrying a Zara shopping bag, and a seemingly discarded painting of Eva Perón next to sculpted trash bags. Dufour draws from local vernacular aesthetics to produce works that mix Pop, dark humor, and a seemingly nihilist view of social and political reality. Seeing the portrait of Evita Perón in that dumpster still-life made me think of the desire, and yet the difficulty, of discarding history.

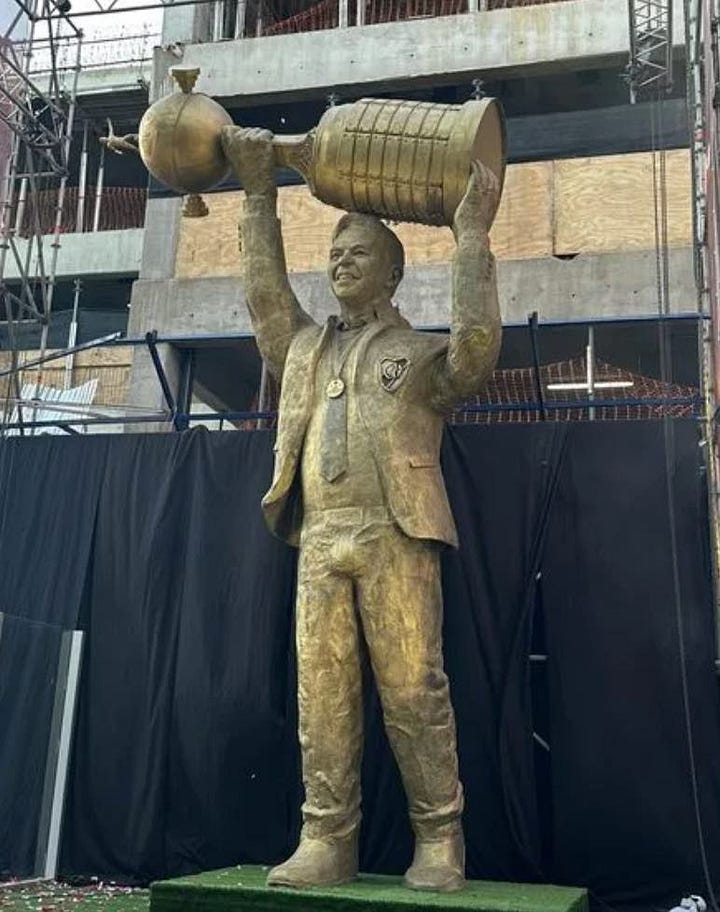

The undying myth of Evita tells us a bit of how pop culture icons are formed in Argentina. Yet another example, albeit in a totally different category, is the recently deceased figure of Diego Armando Maradona which symbolizes the height of soccer, Argentina’s secular religion and national pride (particularly at a high point now since Argentina won the last World Cup). Maradona’s effigy is everywhere when you walk around La Boca, so much so that its ubiquity felt to me like the one of El Ché (another Argentinian) which is displayed all over the streets of Havana. This widespread vernacular form of mini-monumentalism is employed not only to remember deceased figures but living ones. This is the case of what made headlines in local Buenos Aires news this past week: the unveiling of a statue honoring Marcelo Gallardo, the ex-coach of Club Atlético River Plate, one of Buenos Aires’ most successful soccer teams with many championships under its belt. Thousands of fans contributed used door keys toward the casting of Gallardo’s bronze statue. However, at the unveiling everyone noticed that the statue showed a giant bulge in his pants, which caused a controversy, although some of his fans joke that it does take a ballsy coach to lead a soccer team to triumph. I might add that there is a sculptural tradition of depicting protuberant crotches in soccer figures, as a recent statue of Cristiano Ronaldo proves.

—

I was lucky that my hosts arranged for me to stay in the Barrio de San Telmo, the oldest neighborhood in Buenos Aires and a bohemian, middle-class area with lots of cultural activity. Most importantly it is the place where the cartoonist Quino (1932-2020) lived for 22 years and the urban environment that inspired his famous comic strip, Mafalda, which ran from 1963 to 1974 and was a South American counterpoint of sorts to Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts, albeit with a political conscience that largely catered to an adult audience. Quino’s drawings were of enormous influence and inspiration to me as a kid, and I practically learned to read while reading comics like Mafalda; it was also my first introduction to the politics and the culture of the 60s (it was the first time I heard of the Vietnam War, of Fidel Castro, and even The Beatles). Mafalda is an average middle-class 6 year-old kid who goes to school, doesn’t like to eat soup, and worries about the general state of the world. Her classmates/neighbors/friends represent the spectrum of the foibles, qualities and quirks of society: they include Susanita, who only dreams of being a housewife and having babies; Felipe, who is always anguished, second-guessing himself about everything and stressed out about school and life in general; and Manolito, whose father (a Spanish immigrant) owns a local grocery store (almacén), wants to be a great businessman and is obsessed with cutthroat capitalism and money.

One can pass by Quino’s home in San Telmo; nearby is also a small monument to Mafalda which tourists (like me) come visit to take selfies. I also made a point to see another key landmark in the Mafalda-verse: Manolito’s grocery store, el almacén Don Manolo, is an actual store in San Telmo that Quino used as reference for his comic strip and today has also become a kind of historic site for fans. In 1988, not long after the return to democratic rule in Argentina with the presidency of Raul Alfonsín, Quino made an inscription on the lower section of the façade of the Almacén Don Manolo, which reads: “to the only president capable of showing us that all that one learns in school can be true! To Raúl Alfonsin, with gratitude and affection, Quino.”

I also feel gratitude and affection toward Buenos Aires, a city where — paraphrasing Funes —every word and every gesture endures in its implacable memory.

With thanks to Mayra Zolezzi, Victoria Noorthoorn, Carlos Gamerro, Cecilia Rabossi, Andrés Duprat, Fundación Proa and Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires