Chasing the Shadows of Butterflies

(A beginning-of-year note)

I don’t have much to write about today, except to share a brief reflection concerning how to tackle the forces of the future, which is something that we all are getting ready to deal with on this first week of the year.

The only dog I ever owned in my life was named Igor. My family got him sometime when I was 6 years old, and he was with us for about a decade. We named him after the Russian composer, Igor Stravinsky —and he was a worthy pet for a musical family, often sleeping under the piano while my sister practiced Chopin’s Ètudes. He was a mutt, although we were told he was an Irish Setter. Whatever he was, he was kind, affectionate, very emotionally attached to us, although just like most of us in our family, not very street-smart.

Another peculiar aspect about him was that he loved chasing the shadows of butterflies in the garden, which once inspired my brother to write an epistemological poem about the search of truth, referencing Plato’s cave. Igor also loved getting out of the house —unleashed— and peeing on every tree around the block, (which is known as urine marking). This he would do whenever we opened the kitchen back door to take out the trash.

One of those times, when we were out except my brother, who —always distracted by philosophical fluttering shadows of his own—, opened the door and Igor went out to do his tree marking rounds without my brother noticing. My brother went back into the house, not realizing that the dog was already a few blocks away, later disappearing altogether.

Later that night we combed the entire neighborhood looking for him, blowing the car’s horn in the hopes that he would recognize us, to no avail. We never saw Igor again. We were devastated; we could only imagine his anxiety and fear at being lost in the night of Mexico City, and never knew whatever happened to him— whether he was run over by a car, or taken by someone else, or had other misadventures.

I remembered Igor this week while finally getting around to read The Meme Machine, a 1999 popular science book by Susan Blackmore. The book, which argues for a science of memetics, generated quite a bit of a debate when it appeared— receiving a few snubs in the academic world, where some saw its biological arguments not entirely convincing, but a greater embrace in terms of Blackmore’s views on how memes spread culturally. In fact, in many ways, The Meme Machine (which predated social media by several years) became an influential resource to understand online viral culture.

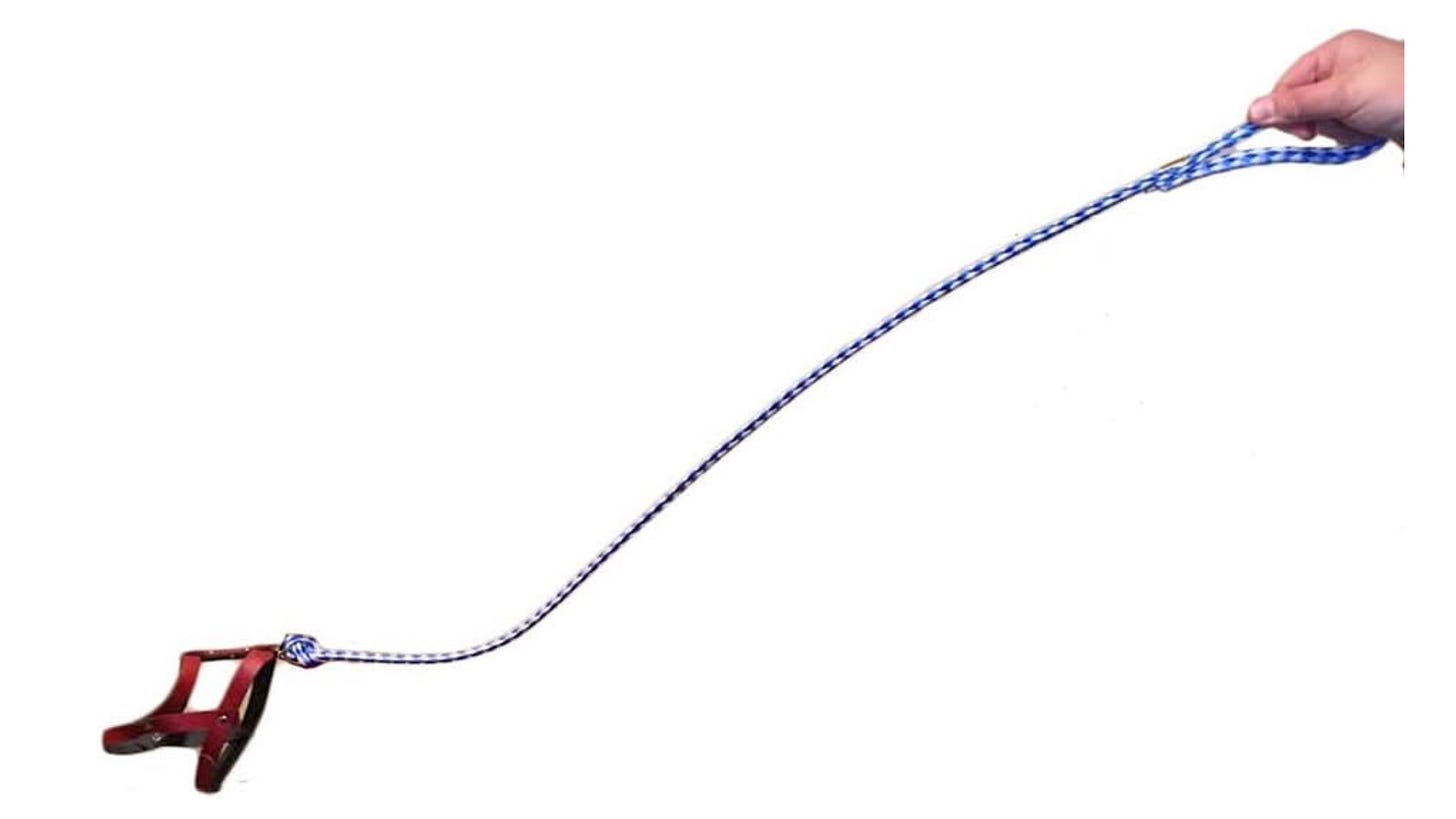

An important metaphor that Blackmore uses in that book is the one of a dog and its leash to explain the relationship between humans and memes. We, humans, are the dog: the carriers of memes, which are defined as units of cultural transmission (ideas, attitudes, expressions, etc.). The leash represents memes themselves, which exert control of us by making us move in certain directions and curb our behavior. Like the dog on a leash, we consider ourselves rather autonomous, but often are not aware of the extent by which the leash (i.e. memes) determine and direct our behavior.

In an interesting way, Blackmore’s theory is a secular/scientific version of the Calvinist philosophy of predestination: Calvinists believed that free will was a mortal’s illusion and salvation was predetermined (although paradoxically one is still responsible for their actions, which is part of the “divine mystery” of the faith). Like the Calvinists from centuries ago, we can be aware of the influence that memes have on us, yet our awareness does not necessarily liberate us from their influence.

But the interesting question for me has always been how one could apply Blackmore’s metaphor not to religion but to the art system.

The interdependent relationship between the rebel and the system ( in this analogy, the dog and the leash) is a common theme, from Camus and Gramsci to the Chantal Mouffe of The Democractic Paradox. The dog (say, the artist) needs the leash (say, the institutional and commercial complex; the external forces, of a political, economic and social nature, that establish a general framework for the art that is acceptable, desirable, or encourageable to produce). The artist, as the dog, is, as previously mentioned, in its mind a free actor maybe somewhat, but not entirely aware, of the limitations that the leash is imposing on them. The artist sees as their mission to push the envelope, but they are unlikely to push it to the extent of making exhibiting in the first place impossible (an exception in this regard was the case in 2007 when Christophe Büchel pushed MASS MoCA to cancel his sprawling, never-ending show “Training Ground for Democracy.”)

Should the dog free itself from the leash, it would become a stray— free to roam everywhere, but at the same time thrown into the unknown, lacking shelter and food and become vulnerable to disease and harsh environments. This kind of freedom, in artistic terms, also represents banishment. Conversely, artists who are too attached to a leash —the comfort of institutional validation, be it by the market, academia, or even governments— are often regarded as “official artists” or “artists of the system”.

I surmise I have played the role of leash at least a few times in my life when I worked as an arts administrator in museums— or at least my role was more leash-like than dog-like. I felt, for instance, that was given the role of leash a few years back when invited to do an artist-as-guest-curator project at a museum. I personally knew several of the artists in that museum’s collection, and decided to reach out to a few of them to start a conversation about where and how to install their works in that exhibition ( I wanted to try an experimental approach for the hang, which required a conversation with the artists). One of them, who is an older and established artist who I am also friends with, was also known for his rebelliousness, and from the onset he wanted to do things his way, making budgetary demands that the museum was unable to meet. We played a sort of dog and leash game back and forth, during which he threatened to quit the show. To his surprise, I told him that I indeed thought he should quit, as there was no way I was going to get the museum to meet his demands. He decided to remain in the exhibition with the conditions I had previously outlined.

However, my attempt to equate the curator as a leash and the dog as an artist might be a mis-application of Blackmore’s theory. Perhaps the better analogy is that the leash is our cultural unconscious: the reasons for which we do the things that we do without fully knowing why we do them. We as cultural producers of every kind are the meme carriers, with a general sense of autonomy and independence, but not entirely aware of the extent to which we are in fact completing a picture already established by a dialogic superstructure. In other words, whatever sense of originality and disruption we might have of our work will only look like small variations from the distance of a few hundred years.

Perhaps since that teenage experience of losing Igor I have regarded the notion of the leash as something more than what is understood from its conventional definition. In gag gift stores one can purchase a leash to hold an invisible dog leash (as one can also do to support The Invisible Dog Art Center, an arts organization in my neighborhood that incidentally I do recommend supporting).

But in practice, that which really is invisible is the leash, and we are the visible dog. We are the real effects of the way in which unseen forces influence us. We chase the shadow of the butterfly, unable to see the butterfly itself. But this quest is not, I want to believe, an entirely futile task: occasionally the work we do brings its reward, and if we are patient and methodical we might be able to get to see the butterfly land on its very own shadow. We might even get to challenge the meme machine— not by trying to liberate ourselves from the restraint, but, accepting it as part of our life, fulfill our predestined fate as radical rebels and, so to speak, wag the leash.

well said!