This past weekend, while visiting Greenwich, Connecticut—one of the most affluent towns in the United States—I wandered through one of its neighborhoods, lined with elegant homes that evoked a carefully curated sense of history. As I walked, I found myself reflecting on how beauty and truth are often at odds, brought to mind by the story of a particular artist who embodied that very tension.

If one had to name the most prolific and commercially successful artist in U.S. history, Thomas Kinkade might come to mind; or perhaps Andy Warhol, O’Keefe or Basquiat. And if the question were about artists who helped shape Americans’ understanding of their national history and cultural identity, Winslow Homer, Jacob Lawrence, or Norman Rockwell would probably top the list. Yet none of these artists—not in sheer volume of sales nor in the everyday ubiquity of their work—approaches the legacy of one in particular. Virtually absent from most art history books —as his work was not technically or conceptually innovative nor transformative — but well-known to the decorative arts field, this artist nonetheless sold an estimated ten million works in his lifetime and crafted a visual language that arguably shaped America's collective self-image more than any other. His name was Wallace Nutting.

I first became aware of Nutting in 2003, thanks to an exhibition at the Wadsworth Atheneum and an accompanying publication by Thomas Andrew Dennneberg, “Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America”— which explored the key role that Nutting played in the Colonial Revival movement in the United States— an unlikely path shaped by circumstance and serendipity.

Born in Rock Bottom, Massachusetts, he studied theology at Harvard and became a Congregationalist minister, serving in parishes from Seattle to Maine. However, at the age of 43, he was forced to retire due to neurasthenia—an often-diagnosed 19th-century condition marked by fatigue and headaches, roughly comparable to what we now describe as chronic fatigue syndrome. To combat his symptoms, Nutting took up bicycling, a common prescription for neurasthenia at the time. As he cycled through the New England countryside in the 1890s, he experienced what he later described as an epiphany: a profound sense of nostalgia for the fading agrarian landscape and crumbling colonial architecture.

At that point, the United States was just over a century old—a young nation still in the process of constructing a historical identity. Writers like Washington Irving had begun this cultural work earlier in the century, mythologizing the Dutch colonial past. The romantic landscapes of the Hudson River School may also have shaped the visual framework within which Nutting perceived the world. Yet Nutting’s response was more urgent: he felt compelled to preserve what he saw as a vanishing way of life. Photography, newly accessible and mechanically faithful, became his chosen medium. He trained himself in its use and began documenting not only landscapes but also colonial cottages and interior domestic scenes.

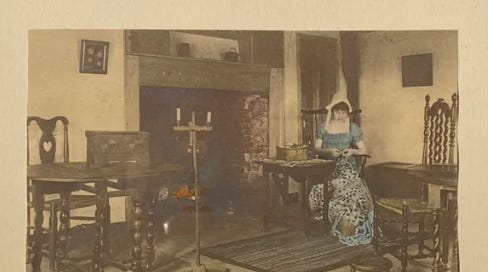

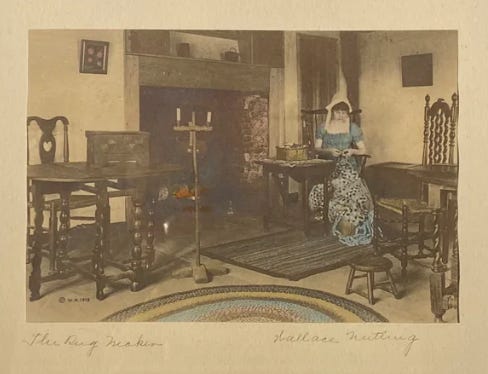

The irony, of course, is that this documentation—as Dennenberg’s book also suggests— was often anything but authentic. Many of Nutting’s most iconic interior scenes were carefully staged, complete with models in period costume and props that conjured an idealized, invented past. His project, then, was more of a romantic reimagination than a historical account—an act of imaginative restoration that blurred the line between history and nostalgia.

Nutting’s intuitive approach was immensely successful: he unquestionably tapped on a collective desire to embrace the American past, which probably was prompted by the rapid modernization of cities and the sense that simple country life was vanishing. Nutting rode this wave, and quickly went from being an amateur photographer to a style impresario. At its height, his studio included 200 employees, including about 100 colorists who hand-tinted his photographs. By some accounts his studio was making more than $1,000 ($31,000 of today’s dollars) on a daily basis. At some point in the 1930s it was common to have a Wallace Nutting hand-colored photograph at home. The works were usually signed but likely not by his hand— either a stamp or an embossed studio label.

Nutting churned out a wide variety of publications, starting in 1910 with a decorative arts book, Furniture of the Pilgrim Century, 1620–1720. His “Beautiful” series from the 1920s (“ is a collection of about a dozen books depicting picturesque landscapes and historic architecture of New England and the East Coast (Massachusetts Beautiful, New York Beautiful, Connecticut Beautiful, Vermont Beautiful, New Hampshire Beautiful, and so forth). He published extensive visual handbooks with thousands of photographs of American and Windsor furniture.

In many ways, Wallace Nutting can be seen as a precursor to Martha Stewart. He crafted a powerful personal brand rooted in an idealized domestic vision that resonated deeply with the American middle class. Through his mail-order catalog, he offered hundreds of hand-colored prints alongside reproductions of colonial-era furniture, effectively commodifying the past through a benign and comforting lens. Nutting’s images didn’t just decorate homes—they shaped a sense of identity for his audience, offering a nostalgic blueprint for how Americans might imagine their heritage. In doing so, he built a commercial empire and became a millionaire, turning historical reverence into a remarkably successful lifestyle business. But it is important to look at what, precisely, this selective idealized image he constructed was about.

It is worth delving into the Nutting family’s history, especially given some of its surprising twists. I was intrigued to discover that, according to the family’s genealogical lore, the very name Nutting might trace back to Governors Island in New York—a small island less than a mile from where I am now writing these lines. Originally settled by the Dutch in 1624, the island was called Noten Eylandt (“Nut Island”) due to its abundance of nut trees. In a 1908 genealogical book, John Keep Nutting (a distant relative of Wallace) proposed that the family name derived from this island, and that the family patriarch, John Nutting, once owned the land before selling it to the government and relocating to Massachusetts. The same account claims that he was later killed during King Philip’s War in 1676—a violent conflict between English colonists and Native American tribes—and that his severed head was displayed as a warning to settlers. Wallace Nutting is mentioned in the book, and although we cannot confirm the accuracy of these stories or how much Wallace himself endorsed them, what is clear is that his life’s work was steeped in a sense of maintaining an inherited tradition.

Learning, however, of the incident about John Nutting’s head reinforced what is clearly represented in Wallace Nutting’s lifelong quest to create a colonial past that explicitly erased people of color— both natives and Blacks— from his constructions of the American landscape.

Viewed through a metaphorical Benjaminian lens, as it were, Wallace Nutting’s camera becomes a kind of inverse angel of history: rather than facing the wreckage of colonialism and slavery, it turns away from it, projecting a tranquil, pastoral vision rooted in selective memory. His mechanically reproduced images—commercially successful and widely circulated—offered a placid, bucolic past reminiscent of early 19th-century Romanticism. But unlike Walter Benjamin’s angel, who is helplessly blown forward by the storm of progress while staring at the ruins, Nutting’s vision collaborates with cultural amnesia, crafting an aesthetic that soothes rather than confronts, erasing rather than reckoning.

What makes such nostalgic misrepresentations especially insidious is the comfort they provide through erasure—a comfort that places the burden of truth-telling on those historically excluded. When these individuals challenge the sanitized narrative, they are often perceived as disruptive, as if discomforting the dominant story is more troubling than the violence of its omissions. The true harm lies not in their protest, but in the silent, systemic deletion of their histories. This dynamic—where the labor of correction falls on the marginalized, while discomfort is reserved for the dominant—has been incisively analyzed by Black writers such as James Baldwin and bell hooks, who reveal how institutions consistently prioritize white comfort over historical accountability.

Thinking about this, I was reminded of another example of historical revisionism and nostalgic landscape construction. Between 2012 and 2016, I periodically traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico periodically to conduct research for an art project at the invitation of SITE Santa Fe, which was launching a new artist-in-residence program. I’ve long been drawn to the city’s picturesque architecture—something I hope to write more about one day—perhaps because I’m susceptible to the nostalgic mood evoked by stucco walls, colonial-style vigas, rounded corners, and flat roofs. But I was also struck by how historical memory is distorted there, and trauma buried. I met many longtime New Mexico residents who identified as Spanish, even though their families had lived in the region for more than five generations—making them, literally, less Spanish than I am (and I would never call nor consider myself Spanish). It was also in Santa Fe that I first learned about the controversial Fiestas de Santa Fe, held each September to commemorate the 1692 return of conquistador Diego de Vargas following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, when the Spanish were expelled by Indigenous peoples. Though the festival celebrates what is often portrayed as a peaceful re-entry, de Vargas’s return was in fact followed by repression and violence, including the public execution of 70 Pueblo resisters in 1693 in the city’s central plaza. The festival’s sanitized narrative masks the deeper trauma of colonization. As a result, the Fiestas de Santa Fe have become a paradoxical space: on one side, a celebration by descendants of the Spanish; on the other, a somber period marked by silent protest from descendants of the slain Pueblo leaders. Much of this tension lies just beneath the surface of Santa Fe’s undeniably beautiful and romanticized landscape: a set design for a pleasant tourist experience and for illustrating the picturesque stories one might tell visitors.

It hardly needs stating that Nutting’s example feels especially resonant today, as we find ourselves in the midst of a cultural war marked by efforts to construct new fictional and amnesiac landscapes—this time under the banner of anti-DEI backlash and the zealous campaign to purge so-called critical race theory. Though Nutting’s hand-colored photographs may now gather dust in thrift shops or circulate on eBay, the cultural sentiment and ideological impulse that produced them is far from obsolete. If anything, it is being repackaged and redeployed, still shaping how history is sanitized, remembered, and weaponized. In “The White Man’s Guilt”, published in 1965, James Baldwin wrote:

"To accept one’s past—one’s history—is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used: it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought. The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do."

But I think we already know all this. We know deep down that lying to ourselves feels acceptable when it feels good, and perhaps for that reason we can’t bring ourselves to instead see beauty in truth, as ugly as that truth might be. In On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry argues that beauty is the prelude to justice, but we might want to invert this idea, and still not entirely contradict Scarry, by saying that justice, the pursuit of truth, is what we should seek to capture. And truth, I believe we know, is complex, often uncomfortable, seldom the perfect stucco house in the Southwest, nor the idyllic colonial New England cottage— and most definitely, not something one can order from a catalogue.