Over the course of several decades now, James Elkins has written some of the most influential books on the subject of visuality— an area that straddles between art history, art theory and the visual studies. “The Object Strikes Back: On the Nature of Seeing”, from 1996, is about how images affect and change the observer. “Pictures and Tears” from 2001, is about the emotional impact of art works. His first book, “The Poetics of Perspective”, from 1994, was very influential to me as an artist. He is unusual in the field of art history in that his books draw equally from the history of art but also from fields as diverse as psychology, optics and religion. I have particularly shared, from the beginning of my career, his intense phenomenological curiosity on specific traditions, tenets, and behaviors (which will be clearly obvious to anyone who regularly reads this column).

I have known Elkins for more than 30 years, dating back to the time when I was bright-eyed undergraduate art student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Yearning to study theory, I begged Lisa Wainwright, then Dean of the school, to allow let me take his graduate seminar, “Ambiguous Meanings”, to which she reluctantly agreed (“Enjoy the ambiguity”, she finally said, as she signed off on a piece of paper after me chasing her down the hallways of the school). In that class we plowed through Derrida’s L’écriture et la difference and other equally difficult texts. Many of his classes included some of the material that he, contemporaneously or later, developed into books. One time in that class he put us to do a 3-hour critique of Balthus’ The Street — a grueling process, because after the first half hour of discussion we would not know what to add, and then the conversation would start up again, then stop , and so forth. Elkins experimented with these incredibily long critiques, once doing one which he felt broke the record of all multi-hour critiques using as focus a painting that a student had made in 20 minutes. When I brought up this topic at a public conversation I had with him last night, Elkins mentioned that with these experiments he wanted to show to the students that meaning is not inexhaustible— which is to say that, contrary to what one may think, there is a limit to what can one come up with in terms of interpreting a particular art work.

I remember yet another class when he was exploring the structure of images that are hard to see— sharing historic photographs of torture, medical documentation of deformities and other gruesome depictions, some of which made some students who just could not take it simply exit the classroom (in retrospect, I don’t think it would be something that anyone could be allowed to do in a higher education context anymore). Years after I had left Chicago I reached out to him, first to ask him to write for a project I had made about heteronyms, then to be part of an experimental symposium I organized in Puerto Rico— to my surprise and delight, he always accepted my extravagant entreaties. At MoMA we collaborated a symposium titled “Art Speech” on the dependence of the written text by academia and the pedagogical pitfalls of that dependence in live presentations. In 2015, I invited him in to pitch in as part of an exhibition in Barcelona exploring the work of W. G. Sebald, of which I knew he was a fan.

About a decade ago when I was visiting Chicago I saw Elkins for lunch. That day he made a perplexing revelation to me: he was in the process of leaving art history. This was surprising to me, as Elkins for many years has been the chair of Art History at SAIC, one of the top positions in the field in the US, and even during a period he simultaneously was the chair of the Department of Art History at University College in Cork, Ireland (how did he manage to do that, and also continuing an active publishing schedule is beyond me). But over time, he said, he had grown disenchanted with the rigidity of academic writing and how it impaired creativity (recently he wrote an article about his decision to leave academic writing). Most importantly at that lunch, he told me that he had started writing a novel.

Changing disciplinary lanes at maturity is a risky proposition. Very few of those who excel in one field can successfully move onto another, and I know Elkins is well aware of that (“I know I might fail”, he told me back when we had our lunch). However, there are interesting success stories: for example, at the top of his career as a semiotician, philosopher and medieval historian at 48, Umberto Eco published the murder mystery The Name of the Rose. The reference comes to mind because Elkins is to me an Eco-style writer, someone who is obsessed with books that while supported by the novel structure really are vessels for content (“essay-novels”, as they are often defined).

Over the years, Elkins has organized a few reading groups at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago that delve into what he terms “arguably unreadable” novels, Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and Arno Schmidt’s Bottom’s Dream. Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s last work, is one of the most difficult literary works in the Western canon, densely packed as it is with obscure references of multiple types, neologisms and experimental uses of language —to the point that once Joyce remarked that ideally it would take as long to read it than it too for him to write it (17 years). As to Schmidt’s “Bottom’s Dream”, it is probably the most difficult novel ever written. At 1,334 pages (the 2016 English translation by John Woods is 1,496 pages and weights 13 pounds) the novel is written in three columns and is in essence a conversation between four characters about translating the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Elkins tries to articulate his interest in these novels to the reading group thus: “Our question, in both Joyce and Schmidt, will be what happens when a novelist’s interest veers toward elaborations of language, and away from narrative. What remains of the idea of the novel when it becomes expository prose, essay, constrained writing, collage, or craft (that’s David Letzler’s term for nonliterary inclusions)?”

Note-taking and dreaming (in the case of Joyce, the exploration of hypnagogia, the state between sleep and wakefulness, and the fact that he saw his novel as an exploration of the night) are definitely present in Elkins’ novel, which, ten years after our lunch conversation, comes out this week, titled “Weak in Comparison to Dreams”. The 600-page novel centers on Samuel Emmer, a bacteriologist who works for the city of Guelph, Canada. Emmer is given the task to travel inspect zoos around the world to study the treatment of animals, a task he dreads (Elkins told me that for research for his book he traveled to many zookeeper conferences, sometimes even posing as a zoo historian). Emmer’s travels and his own ruminations, opinions and reminiscences at different points of his life constitute the core of the novel.

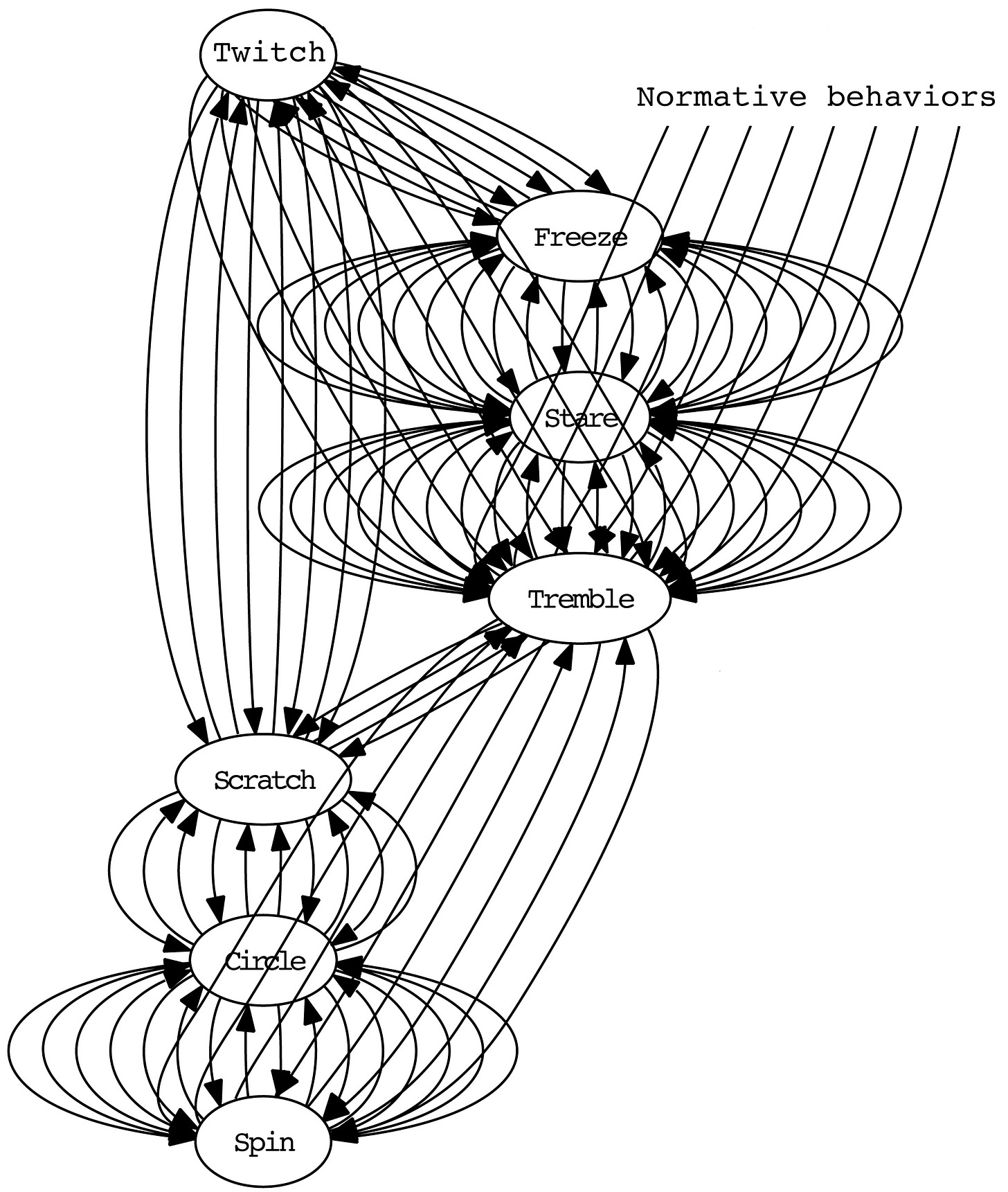

I was uncertain what to expect from Elkins’s writing, and, being no literary critic, I am unable to assess the novel with any authority or expertise. However, the first salient aspect that any informed or uninformed reader will encounter in the book is the use of images— photographs, diagrams, historic engravings, etc. — which are used as an integrated device into the narrative, in dialogue with devices such as the ones used by Sebald. While reading the novel I thought about how, when one reads art history texts, the many requirements of the field (citations, stylistic requirements, etc.) tend to stiffen the voice of the author, making it hard to have a personal connection with the reader—and I confess I was worried that the novel would somehow contain the unsavory idiosyncrasies within that tradition. However, Elkins has never been a conventional art historian — his books in my view do retain a very original voice precisely because of their subject matter and the angles from which he explores it—and in addition, I found the narrator’s voice containing the same qualities of Elkins’s when he speaks. It being an essay-novel allows for something that Elkins excels at: taking on an obscure subject – for instance, the walking patterns of certain animals— developing a series of observations drawing from theories and presenting visual evidence or illustration of those theories. In the novel it is hard to know if the theories that Emmer is presenting are real or invented (because they are so obscure it is hard to go into the depths of the web to figure it out), or if they are real but slightly altered as it is the case of the various composers that Emmer discusses at the end, (misrepresenting facts because Emmer is an unreliable narrator and often forgets or confuses things) both in the case of their compositions and their biographies (this element has an interesting postmodern aspect to it, somehow à laMuseum of Jurassic Technology).

Yet art history, or perhaps visual studies, is still present in my mind as I read his work. Perhaps the big picture element for me is the very examination of zoo life by Emmer. I often joke with my friends, speaking of my museum career, that working as an artist inside a museum is like being a monkey who works at a zoo. Perhaps for that reason, and in some ways, as Emmer describes (often with boredom and dislike) what he observes in caged animals, what I observe as a reader is Elkins himself, examining the act of seeing that has characterized his entire career. Just as Emmer examines zoos against his will, Elkins performs the functions of academic life while wanting to liberate himself from its trappings. In the novel, the liberation process occurs through daydreaming and free-association, when one idea leads to another and another —maybe in the hopes to reach the utopian point where, like those marathonic painting critiques, one has exhausted all the possible meanings of every experience.

So many fascinating bits here, especially the parts about dreaming....thank you

loved this, Pablo!