Creditable Unrealities

Building façades as art and metaphor.

In 2008, the Mexican artist Fabiola Torres-Alzaga was traveling through the state of Durango — an area that includes the west flank of the Sierra Madre Occidental and a geographic diversity of mesas, deserts, canyons and forests. Durango’s natural geography has been historically favored by the film industry in both the U.S. and Mexico, so several films have been shot here. It was attractive “for its sky and its light, in addition to cheap Mexican labor, which made it a fruitful place for filming”, said Torres-Alzaga, adding, “I knew this, but I did not know what I could find.”

What she did find included a series of abandoned film sets, mainly ruined façades of buildings, that she later learned belonged to a 1989 film titled “Fat Man and Little Boy”, starring Paul Newman. What interested her was how these rather incongruous architectural remnants constituted “a fragmentary geography, and its logic and continuity are dependent of the camera that sees them and the editing that brings them together.” I was fascinated by Torres-Alzaga’s photographs, which offer in my view not just the full picture, if you will, of a process of artifice, but they also document the vestiges of an illusion, a careful and real register of something that was never real in the first place. In an odd way, the depiction of the ruin of something false (or something used to simulate something real) gives it authenticity. But even more interesting to me, and perhaps even more poetic, is the fact that by documenting the understructure of the filming process, Torres-Alzaga was also presenting the abandoned materials of that temporary magic: an archaeology of fiction.

Beyond this instance where photography, illusion, and architecture intersect, Torres-Alzaga’s explorations of the “blind spots” of artifice and illusion are interesting to think about as coda to what constitute political blind spots of sorts: the fascination by people with means and power to construct public buildings that double as narcissistic markers of their legacy. In Mexico, as in many other countries, politicians rush to build various public works before their end of their term (building hospitals, schools, bridges, and, of course, art museums), so that their projects can bear their name and/or they can take the credit for them—something I often refer to as the Ozymandias complex, mainly because the moment those politicians go away the institutions they created rarely evolve and their grandiose façades begin to crumble. Among the many examples in Mexico is the grand cultural project of the Vicente Fox administration of the early 2000s. For a while the administration wanted to build a major art museum of contemporary art, but the project faced the stiff resistance of the Mexican art world, most of who argued that instead of creating a shell of a building with no collection inside the culture ministry should direct the resources to Mexico’s underfunded and languishing art museums, which count in the thousands but in contrast to the country’s archaeology museums receive a much smaller share of federal support. Then the Fox government moved to create what is known as the “White Elephant”: the Biblioteca Vasconcelos, a massive library designed by architect Alberto Kalach. Hastily opened to the public in 2006, the library had a lot of structural problems including water infiltration and leakage (on the very day of the inauguration ceremony, a friend who was there told me, “it was raining inside the building”). After the opening ceremony, the building had to be shut down for 20 months for repairs.

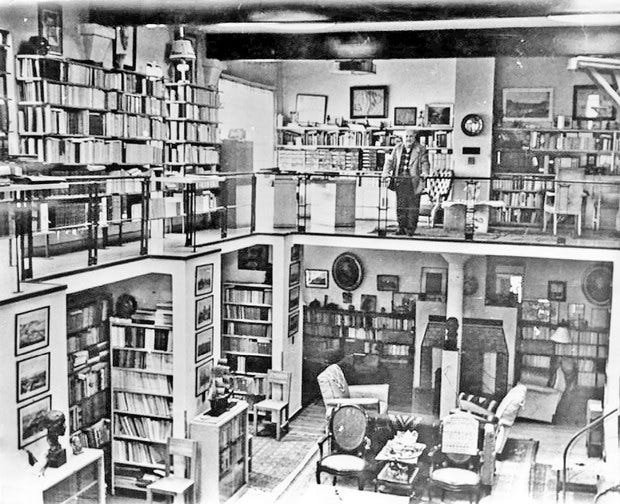

A public building for a library, must be said, is also a double façade: large collections of books are in themselves status symbols, representing erudition and respectability. In Mexico, the emblematic example of communicating the status of public intellectual through the display of a vast library was established by Alfonso Reyes- probably the most important man of letters in Latin America in the first half of the 20th century. Reyes, who was a diminutive man, assembled one of the largest and richest private libraries in Mexico —with great emphasis in classical antiquity and Spanish language literature. He later donated his library to the nation, and now it is open to the public, known as Capilla Alfonsina. For better or worse, subsequent generations of Mexican writers had to measure their living quarters in relation to that example; so more often than not every Mexican intellectual’s home was entirely filled with books.

But of course, as I already suggested, the use of books as backdrop (nor museum façades posing as institutions) is not exclusive to Mexico. And not only is the sale of books by the foot a common source of income for used bookstores, but it is also common for zoom backgrounds (as one zoom background site says, “who doesn’t want to look smart?”)

Whether a museum building, a fake bookcase or a Zoom background, façades serve as cosmetic symbols that are, at best, aspirational (hoping to visualize what we want to be) and at worst, shameless imposture (offering something that we know is not there), with many times it being something in between: “fake it ‘til you make it” practices are usually predicated on the idea that one eventually will reach a substantial product (e.g. the politician hopes that the museum will one day function effectively as one). But as art works are concerned, the best place for them is somewhere in between: the ability to create an illusion but somehow with the complicity of the viewer.

In the U.S. the artists engaged with Institutional Critique (from Michael Asher onward) zeroed in on the symbolism of museum buildings and the way they enhanced the names and reputations of donors. There, the creation of institutions that trafficked in parafiction (to use Carrie Lambert-Beatty’s term) as well as their accompanying museum buildings or containers became a genre into itself, from real museums that excelled in constructing baroque ambiguities like the Museum of Jurassic Technology to Maurizio Cattelan’s The Wrong Gallery (permanently closed, so you could never get through the door). Façade art like that helps us reflect on what would be the art world version of talking about books you haven’t read (i.e. talking about shows you haven’t seen) by liberating us from seeing anything beyond the door. Like in Saint Exupery’s The little Prince, the pilot/narrator is asked to draw him a lamb and, unable to draw it, he instead draws a box with a peephole that ostensibly contains a lamb inside, and the Little Prince is fascinated.

An artist that I admire and who is an expert in containers and façades recently and unexpectedly involved me in one of his projects. Jon Rubin, based in Pittsburgh, is known for his social practice work, which includes his collaboration with Dawn Weleski Conflict Kitchen and Circle Through New York, a project commissioned by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in collaboration with Lenka Clayton. But one of Jon’s great abilities includes inserting art into unexpected spaces (like he did when he turned a Wafffle shop into a talk show), emptying one place to fill another as when he turned an entire estate sale in Pittsburgh into a found object to be sold in Shanghai, and staging painstaking recreations, as when he reconstructed the apartment of Iranian artist Sohrab Kashani at the Mattress Factory Museum.

More recently, he undertook a façade project titled The National Museum. The project description is this:

The National Museum repeatedly asks which stories, histories and futures are deemed worth saving and which are ignored or forgotten. Each month, a different artist is invited to change the name of the museum.

The National Museum is a public art work in the form of a fictional institution that repeatedly reckons with which stories, histories and futures are deemed worth saving and which are ignored or forgotten? How does a nation or city or neighborhood decide what to collectively remember? Who gets to decide what museums’ collect, display and commemorate? What role can artists have in this conversation?

I asked Rubin to elaborate on this façade project. “In this way, the conceptual play upon the idea of the façade is an integral part of the work for both the artists and the audience.”

The idea of the façade does have a connection with our recent collective experiences with the pandemic, where we say many empty storefronts. “Like many downtown properties after Covid, the building facade has its windows papered over so that no one can see inside. So, to a viewer, it might appear as if The National Museum is coming soon, or perhaps long closed. I’m interested in the simple magic act that can occur when the viewer is left to conjure the possible contents of an entire museum [and] in how the project approaches the notion of a museum as a malleable medium--an institution where an imagined set of social agreements, stories of the past, and visions of the future are fabricated.”

So I was invited to be the inaugural artist to propose a name for the National Museum’s façade. The question then was what name to give the museum. Ultimately, I reasoned that façades are the most direct indicator of the time when they were built: they are the things that we try to use as visual reference to identify a city we know in a historic photograph; they are time markers. And when it comes to museums, they traditionally seek to project timelessness, especially those august institutions whose neoclassic façades promise a container of art for the ages. So I thought that this façade should be the threshold not of art history but of our own awareness of that history and our minuscule place in it, knowing that the present that we are living so vividly will soon wash away, largely unimportant within the broader scope of human life. In 2001, doing research on people who consumed ecstasy, I was struck by the effect that their drug had in some people’s temporal awareness, and how it resonated with my own (drug-free) experiences. Thus the phrase “I have nostalgia for the moment I am living”, which gave the inaugural title to the National Museum.

Culturally, in the 21st century, we are a culture of façades: the fake and glamorous representations we make of ourselves on social media, the way institutional and political images are polished and impeccably presented through advertising and press releases, the beautiful Zoom backgrounds that hide the mess in our apartment. We speak about books we haven't read, we opine about issues we don’t have the time or energy to meaningfully study to have an informed opinion. And then that façade we created of ourselves becomes us. As Octavio Paz once wrote:

El otro

Se inventó una cara.

Detrás de ella

vivió, murió y resucitó

muchas veces.

Su cara

hoy tiene las arrugas de esa cara.

Sus arrugas no tienen cara.

The Other

He invented himself a face.

Behind it

He lived, died and resurrected

Many times.

His face

Today has the wrinkles of that face.

His wrinkles have no face.

We might not be able to overcome that overwhelming social pressure to construct those false presentations of the self, those set designs made as if for a hypothetical Hollywood film about our lives. But admitting that we all are complicit in this complex collective construction of realities will makes us more authentic and might prove to be a more enduring statement than the myriad Ozymandias monuments today that are likely to languish one day in the desert like those abandoned movie sets in Durango.