[These excerpts are part of a performance that will be presented at the Hispanic Society Museum and Library in New York on June 20th, 2024]

Note: Artist research fellowships in museums are often focused on studying the institution’s holdings — both its collection and its archives, which is in essence considered its treasure. Perhaps because of my own professional work as museum staff over many years and my general focus on people instead of objects, I am instead drawn to other aspects of museums, such as their historical role in the social and cultural contexts where they originated and continue to exist. This is what colored my time over the last few years as an artist research fellow at The Hispanic Society in New York —a unique institution in how it was formed around the reverence toward Iberian culture and its connection to Latin America. The museum’s building in particular remit my memory to my family history in Mexico, in particular to my grandfather who shared a similar interest in Spain; this manifested in collecting small objects, books, and art — none of it museum-worthy, but expressions, nonetheless, of his passion for all things Iberian— all held in the house in Colonia Roma, Mexico City, where I spent my first four years of life, and which in itself held an air of museum. Many of these old objects, books, and memories remain in my family, and constitute the narrative material of the present performance. These objects remit to an idea of Spain, constructed from the distant New World in the also now remote mid 20th century. Cuarto de Pegar tries to make sense of those forms of distant constructed memories, and how they manifest in remnants —photographs, stories, and objects— that evoked that even more distant, and sometimes imaginary, past.

Had the Spanish Civil War not happened, neither the cuarto de pegar, nor I, would have existed.

Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude opens its second chapter with the comment that on the day of Francis Drake’s assault to Riohacha in the 16th century, the cannon fire caused such trauma to the great grandmother of Ursula Iguarán that her family moved to a faraway ranching community, where they met the family of José Arcadio Buendía. This event thus became defining in the unfolding of the history of the Buendía family.

My family’s history is similar. Mexico’s president Lázaro Cárdenas, in 1937, offered asylum to the Spanish Republicans who have fought against Franco, resulting in an immigration wave of about 25,000 Spanish nationals to Mexico. A group of these immigrants were prominent writers.

My grandfather, Ignacio Helguera, was a businessman and also an amateur writer with a particular fondness of Spain, opened his house in the street of Orizaba in Colonia Roma to organize a series of tertulias, where some of these writers would lecture and/or read from their works. The tertulias attracted young Mexican writers including my uncle Eduardo, a young poet at the time. One night he brought his sister, Beatriz, my mother, who in turn met Ignacio’s oldest son, Luis Ignacio, who became my father.

In our becoming, to what extent are we becoming for others?

Where do we abandon the expectations that those we love had for us?

The nostalgia we have for places where we have never lived,

The desire of an unlived imaginary life sometimes becomes a very real vacuum, a fervent desire to grasp something ungraspable, and when we age and know this is out of our hands, we hope those who come after us can finally realize it; then we place those unrealistic expectations, that Sisyphus boulder, onto the next generation.

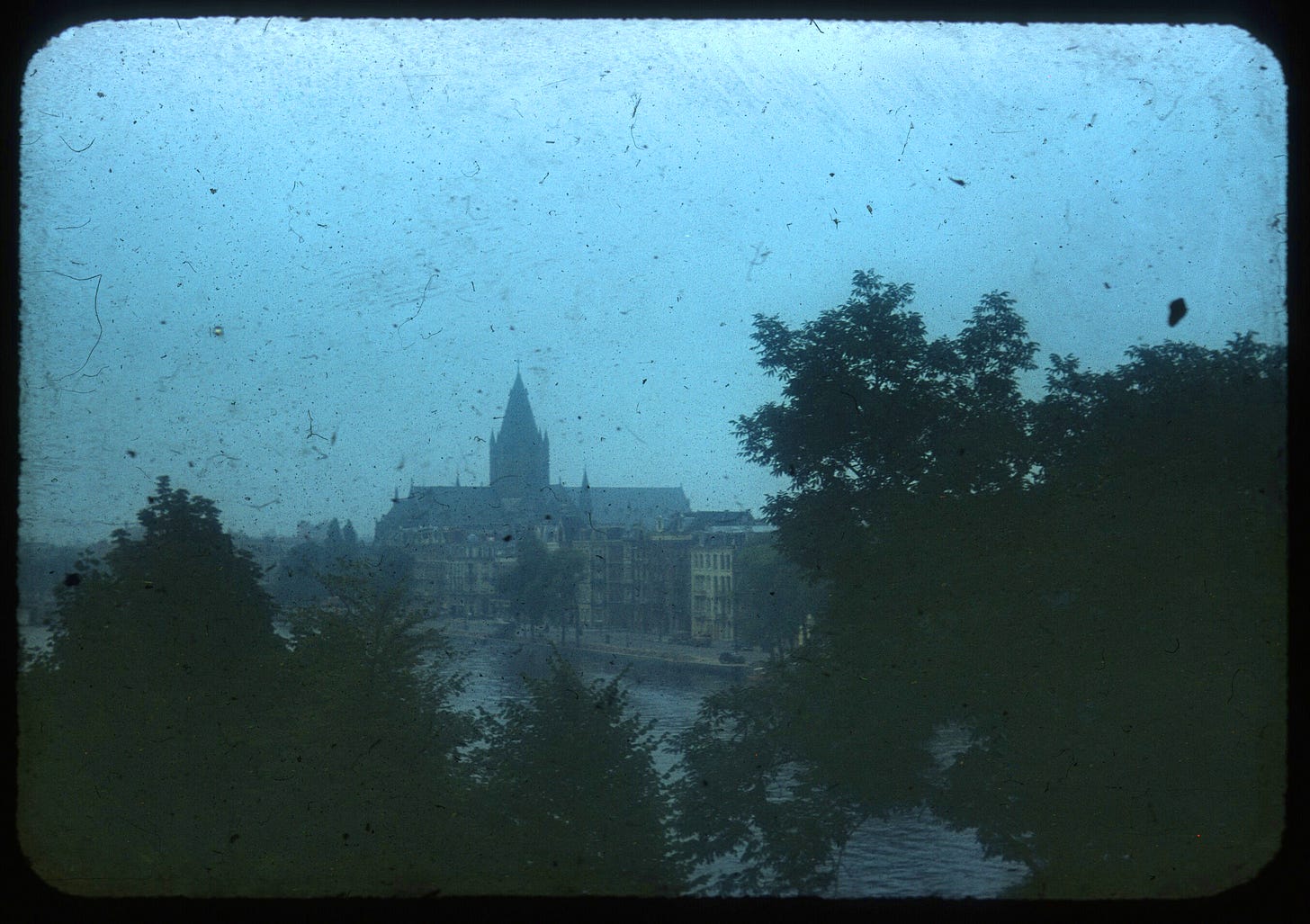

In 1951, my grandparents traveled to Europe. Neither of them had ever crossed the Atlantic, even while Europe had been a fascination to my grandfather. He brought along a camera that took 35 millimiter Ektachrome slides, a product developed in the 1940s for both professionals and amateurs.

They traveled through Spain, France and Italy, throughout the Europe immediately after World War II. When they returned, my grandfather had hundreds of slides which we placed in carefully organized slide metal bins. My father would remember that often when the family had guests for dinner, my grandfather would take out the slide projector and show his European slides, giving a long lecture about their travels that surely was only exciting and interesting to him, while the captive guests had no choice but to sit through his travel narrations.

I found the slides many years later. It is particularly interesting that none of his photographs have any people in them— he appeared intent to show only buildings. Only once does my grandmother appear in one of them. The Spanish slides are of the traditional places of central and southern spain”, Granada, the Courtyard of the Lions, Avila, Alcalá.

A group of four slides in particular, however, struck me: they are images of the village of Helguera in northern Spain, in the region of Cantabria. It has a church that dates from the 10th century, and the town today only has a population of 110.

I see the images today as the dreams of another. They are, it seems to me, less the proof of someone’s travels than the extant archive of a series of lectures, the visual palette for someone who construct their own self-narrative, which became reaffirmed and perhaps elaborated on lecture after lecture. Memory is about the evolving, capricious creativity through the narrative distance.

Our idealized search for the origin is better realized when the origin is never found, so it can be better idealized. The search of the found origin sometimes ends with a whimper.

A few years before I was born, my family moved into the house of the street of Orizaba after my grandfather died, primarily to take care of my grandmother. It was a very large house with several rooms.

My father decided to adequate one of the rooms as a playroom for the children. Mainly, it was a room for art activities. He decided to glue reproductions of famous paintings that he had taken from books in the house: Velázquez, Goya, Rembrandt. It was a form of haphazard, composite art historical collage. I remember one of the painting reproductions, by El Greco, of a gentleman with a hand in his chest. In my imagination I felt that his hand was in his chest because he had a stomach ache. Did not know much about art history, let alone anatomy, at 4 years of age.

We called it el Cuarto de Pegar- the scrapbooking, or collage room.

My brother took the same idea when he was a teenager, making a collage of his own mainly with reproductions of his favorite paintings, mostly impressionists, and hang it in our bedroom

.

We left the house of Orizaba abruptly when I was 4 years old. It is right at that moment where one barely startz to retain memories. It is impossible for me to know at this point how much of what I remember of that place are authentic memories of things that I experienced and things that I was told, or photographs.

This is perhaps the reason why I am drawn to collage-making and why I make collages every night. I think I am trying to piece together something I have forgotten.

We all have a collage room in our mind, trying to piece together the fragments of our experience, like puzzle, trying to make sense of them and of ourselves.

The day we moved out of the house, in 1975, no one inhabited it again, for reasons that were never clear to us. Because no new memories were created there, for decades we walked by the house, feeling it remained as a mausoleum of intact family memories. The house was in ruins, but sat there empty, slowly covered by ivy and the wilderness that grows within empty lots. Finally one day, a few years ago, when I visited once more, the house was gone and it had been turned into a parking lot. I took a photograph of the last remnants of the house: the red fence of the entrance.

Or is it red anymore? I can’t see the faded color, I can’t tell what is the color of the present object. There are times where experiences that we lived directly do not allow us to see the reality of the ruins. Please someone tell me what color this object is, as I no longer can see anything beyond the images in my own memory. It perhaps has taken the color of the black and white photograph that memorialized it, which is in the end all that is now left- a fixed shadow onto an emulsion layer, silver particles suspended in a gelatin surface in a family album stored in an attic.

Hi Pablo, it is always a pleasure to read your reflections and the delightful and unexpected connections you make. This blog post especially made me excited because it touches on something I have been thinking about constantly as I live for the first time in Bogotá, the city/territory that generations of my mother’s family have lived and died, and which I have constructed for myself all my life. Thank you for sharing. I think I almost glimpsed some red in that fence as I read your words! Saludos!