Curating the Forest for the Trees

Our love/hate relationship with art categories.

In 234 AD, in present day Lebanon, a man who became known as Porphyry of Tyre was born. A polymath, he edited The Enneads, which is the collection of the work of his teacher, Plotinus; he also wrote about vegetarianism and music theory. Most importantly, he was a logician and a philosopher. A defender of paganism, he was an early critic of Christianity, putting into question the various claims of miracles performed by Jesus Christ, seeing them no different from the “magical arts” performed in Greece and Egypt. For his religious skepticism he might have been close to a Christopher Hitchens of the 3rd century. He was vigorously censored by the Roman emperor Theodosius II, who ordered every copy of his 15-volume work Against The Christians burnt. It is believed to be irretrievably lost.

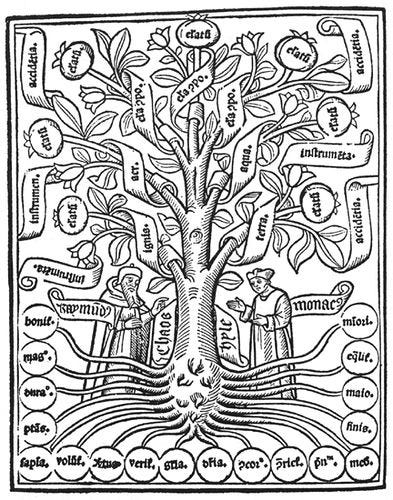

However, one of the lasting, and eponymous contributions to knowledge that Porphyry left us was a system of categorization that anyone who studies the history of both philosophy and logic must learn. In explaining the Categories of Aristotle, Porphyry proposed the use of a tree-like diagram where larger families of categories (genus) are subdivided in species (differentia) until the most specific (or lowest) type that cannot be further divided. This became known as the Porphyrian tree (or tree of Porphyry)— a system of logic of categorization that was taught until the late 19th century. While he did not draw any known diagrams or included them in his works, these were drawn by Boethius, Ramon Llull, and others in subsequent centuries.

The classification tree is in fact a central visual and organizational basis to knowledge, ranging from Linnaeus’s natural classification of plants and animals and Diderot and D’Alembert’s charting of knowledge for their Enciyclopédie in the 18th century to the modern decision tree structures that are key for computational systems and a whole range of disciplines.

Decision tree to determine type of contact lens to be worn by a person.

Today, decision trees are so integrated in our life that they are often a vehicle for memes:

Meme’s aside, the Porphyrian tree often comes to mind for me when I think about curating, as it exemplifies how this practice is often prone to a psychologically fraught process. In short, as I will try to argue, we hate art categories but we can’t live, nor know how to act, without them.

Artists, as we well know, hate to be categorized. The general attitude is that having one’s work described in a category (particularly as part of a style or a movement) is demeaning to the work and limits its complexity. At the same time artists recognize that categories are necessary in order to make the work intelligible to others.

Shortly after I first arrived in New York in the late 90s, I encountered this push for categorization in a very overt way, primarily due to what I perceived as a rush for moving things along. The first social events I attended I was in fact shocked to see how everyone seemed to have elevator pitches at the ready, describing what they did and how they did it. I hated it—plus, I was terrible at it ( I am still terrible at it). I once was invited to participate in a group show of Latino artists at an important alternative art space and wrote an extensive email to the curator explaining how I did not appreciate seeing my work pigeonholed into an ethnic category. I remember feeling disrespected as well as racially profiled.

In my museum life, however, I quickly learned how the use of categories was inevitable due to the pressures of deadlines and the velocity in which things moved. Almost every single day, as a public programmer I was in meetings and conversations with curators and other colleagues that dealt with categories: do we know a Black woman artist based in New York working in performance photography that could teach a workshop? Do we know an artist from Eastern Europe who does work about the history and political impact of the Cold War? Can we think of a conceptual artist who speaks French, is a good speaker, and works with poetry and is interested in Surrealism?

These categories, of course, were completely unspoken about once we would approach the artist in question, but they absolutely informed the thinking process behind the curation of the artist in whatever we were planning. It was in some ways an issue of equity in planning, to ensure that programs would have a diversity of voices. But in order to attain such equity, categories had to be created.

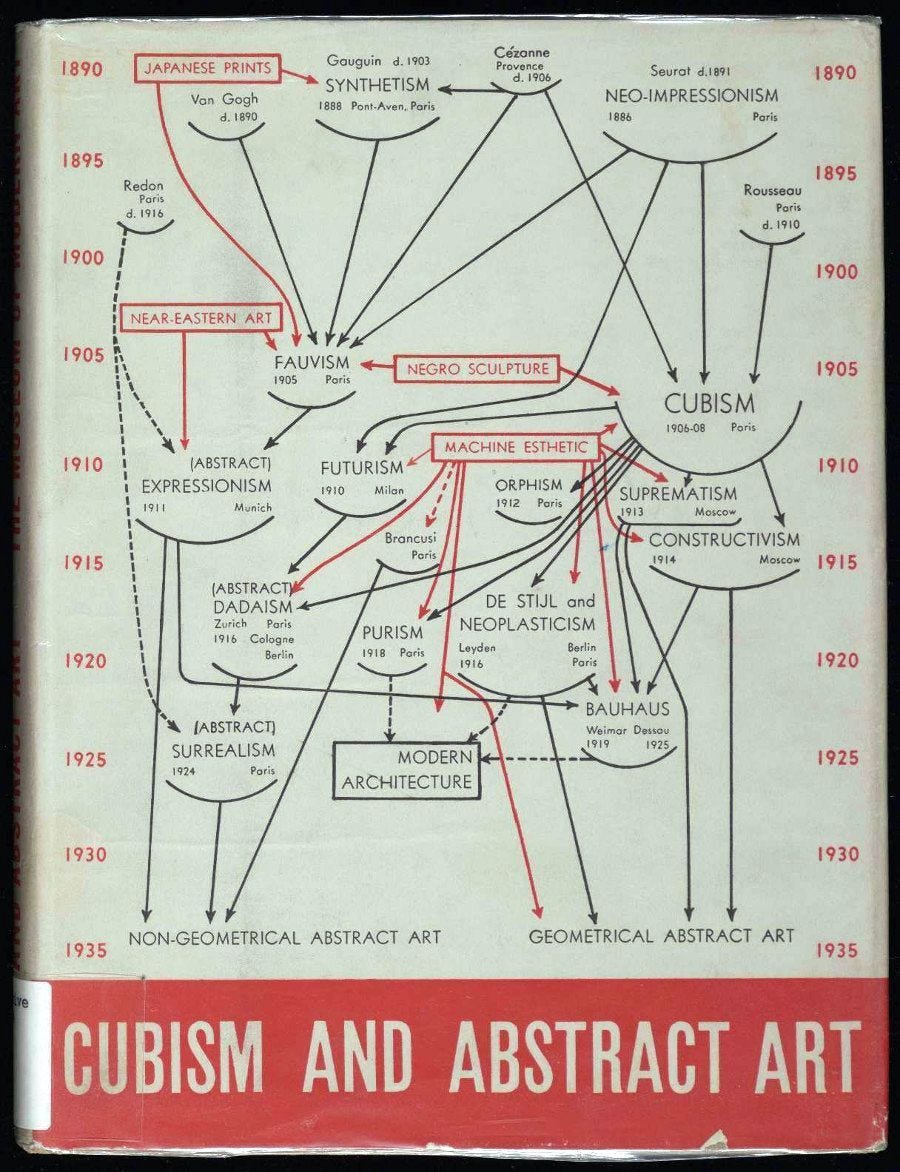

Art history has always operated under terms, categories, and classifications. The cubism and abstract art chart constructed in 1936 by Alfred Barr, which was foundational to the canonical curatorial narrative of the Museum of Modern Art, is a Porphyrian tree of sorts:

As Jennifer Tobias noted in an essay, “the chart has been scrutinized, criticized, historicized, revised, and deliciously parodied.” It remains nonetheless a telling document of how American curators positioned themselves, and the art of their time, in terms of its genealogy and outlook.

But the modernist charting was not just historical or by movement, but also by medium. MoMA’s multiple curatorial department classification (Painting, Architecture and Design, Photography and so forth) was sometimes jokingly described as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”, in reference to the primacy that Painting and Sculpture occupied. More importantly, the artistic style classification of categories largely ignored human categories such as gender and race, which presented some peripheral practices (“Japanese prints”, “Negro art”, “Near-Eastern Art” as tributaries to the great art movements that primarily, if not exclusively, were represented by white and male artists. A meaningful response to this history was created recently by Hank Willis Thomas, who reprised Barr’s chart to reflect to the colonialist legacy of abstraction:

As the 20th century progressed, the boundaries between mediums eroded (artists are less defined these days by medium as they did in the past) and the idea of defining a particular aesthetic with a particular name (as embraced and proclaimed in the form of manifestos by various artists in the early 20th century), gradually went in disuse and the reluctance to be defined into fixed categories became more ingrained; and the social movements of the 1960s made it increasingly clear that racial and gender exclusion were unacceptable.

Regardless, the desire to categorize has never gone away. The endurance of the art historical classification was a necessary museum curatorial practice is partially due to the systemic weight of the bureaucratic structure that governs it. Max Weber went into a classification mode to identify six bureaucratic principles: rationality, hierarchy, expertise, rules-based decision making, formalization, and specialization— all of which are applicable to art institutions.

As an educator, one contends with audiences who want easy answers and explanations —often in the form of catchphrases, key concept, and simplistic terms. One tries to show the complexity of the work amidst the push to simplify for easier consumption. It was perhaps due to that training and the intractable dynamics that I observed in the New York art world that led me to try a classification project of my own.

In 2005, at a time when I was particularly disillusioned by the art world, I wrote a satirical book titled The Pablo Helguera Manual of Contemporary Art Style, written as a social etiquette handbook ostensibly meant to help emerging artists succeed professionally in the industry. It was an utterly cynical and Machiavellian, but also satirical, sendoff. Dedicated to my older brother who was a writer and hated contemporary art (but loved chess), the first chapter made a classification of the art world as a chess game, where Queens were collectors, Kings were museum directors, rooks were curators, Knights were dealers, Bishops were art critics, and artists were of course Pawns (except when the pawn reaches the 8th square when it transforms into a queen (i.e.. a blue-chip artist).

The book was full of diagrams, including a chart of sentimental relationships (which shows the advantages or disadvantages of artists dating curators, critics, and so forth), charts for writing a successful press release, and the social choreography at an opening:

The Porphyrian tree might be little more than a historical reference for science, but it so happens that its taxonomical essentialism can be useful for art. Said in a different way: artworks that break down a problem to its basic components within the realm of fiction and representation can stimulate critical reflection- allowing us to appreciate nuance and see, as it were, the forest through the trees. Perhaps it would be useful to put this essential mechanism of the art making process in the variant of a decision tree:

Pablo, thanks for this. You may be interested in Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt's book https://www.degruyter.com/document/isbn/9783050040660/html?lang=en

which has lots of interesting variants. I'm taking Hank Thomas's timeline for my own lectures (I'll credit you and him of course). And I think you may find this video entertaining -- some curious trees in it:

https://youtu.be/9D1zx3DPL3I

Best, Jim