The following excerpt is part of a presentation I will give this evening at part of the Penny Stamps Speaker series at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, under the program titled “Radical Conversations”.

In 1957, psychologist Leon Festinger coined the term “Cognitive Dissonance”, describing the mental discomfort we feel when we hold two contradictory beliefs. A decade and half later, Eliot Aronson, another psychologist and author of the book “The Social Animal”, furthered this idea to argue that cognitive dissonance is especially strong when it threatens our own image of ourselves.

I am interested in cognitive dissonance because I feel it helps explain, at least partially, why we want art to be radical and transformative, but when faced with the discomfort of that radicality, we instinctively recoil and go back to our comfort zone. “Del dicho al hecho hay mucho trecho” is a common Spanish saying (“from the talk to the act there is a wide gap”), referring to how things are different when they happen than when we speak about them. Such is the case with the curious dissonance around what we intellectually want art to do for us versus what we actually, secretly, use it for, or prefer for it to serve us.

“Make us uncomfortable” is something I have often heard people tell me — museum directors I worked for, funders asking for proposals, and so forth. Yet when one delivers the discomfort, the self-proclaimed masochism tends to dissipate. I have had curators tell me that they want to make dangerous art, but when faced with that dangerous art, and an artist that makes something truly on the edge, they get concerned about the safety and legal implications of that danger. But I don’t blame them, because I have often found myself living within that contradiction, also wanting change and the challenge of the status quo, when at the same time finding myself being afraid of that change.

This paradox likely revolves around our idealized notions about ourselves, what we publicly claim to be interested in and how we want to perceive, which in practice tends to be very different.

Since I begun my art career I felt a great ambivalence with discomfort: I personally consider myself a hedonistic being— someone who loves good meals, travel, bookstores, and so forth, but is also full with a cultural inheritance of Catholic guilt, and also fully convinced that as artist I can’t ever be comfortable while indifferent to the inequities before me. So I feel there is a duty to act, to be uncomfortable, to make others uncomfortable if needed, for the sake of the common good. The great congressman John Lewis, who has spoken as part of this series, said it best in one of his last interviews in June of 2020, just before his passing: “I believe that somehow and some way, if it becomes necessary to use our bodies to help redeem the soul of a nation, then we must do it. Create a society at peace with itself, and lay down the burden of hate and division.”

Louise Bourgeois once said, "An artist can never be still. He must be in motion either physically or symbolically. Physically or symbolically, he must keep moving." (which is a bit ironic because Bourgeois herself had agoraphobia and at least in a physical sense was deeply adverse toward movement).

I also found that discomfort as an art educator in museums. Visitors in galleries want resolution, which they instinctively see it in terms of getting an explanation. What I learned is not only that a so-called “explanation” doesn’t really explain anything, but only becomes a bit of information that seemingly satisfies an urge to dismiss any questions that a work might present. So-called explanations often become the means by which we don’t have to think about art works anymore.

In contrast, the discomfort of not knowing, not knowing what to do with an art work that challenges us, is very productive. When we can’t get it out of our mind, when a video or film or photograph we saw comes back to haunt us, there is an unresolved aspect that we have to deal with sooner or later.

To offer an example, I will share an anecdote from art school, when I was an exchange art student in the University of Barcelona in the early 90s. The school was fairly conservative— a painting department divided in the three sections: those who did academic painting, those who attempted to paint like Tàpies, and those who didn’t fit either of those camps, mostly surrealists. I was placed in the surrealist camp.

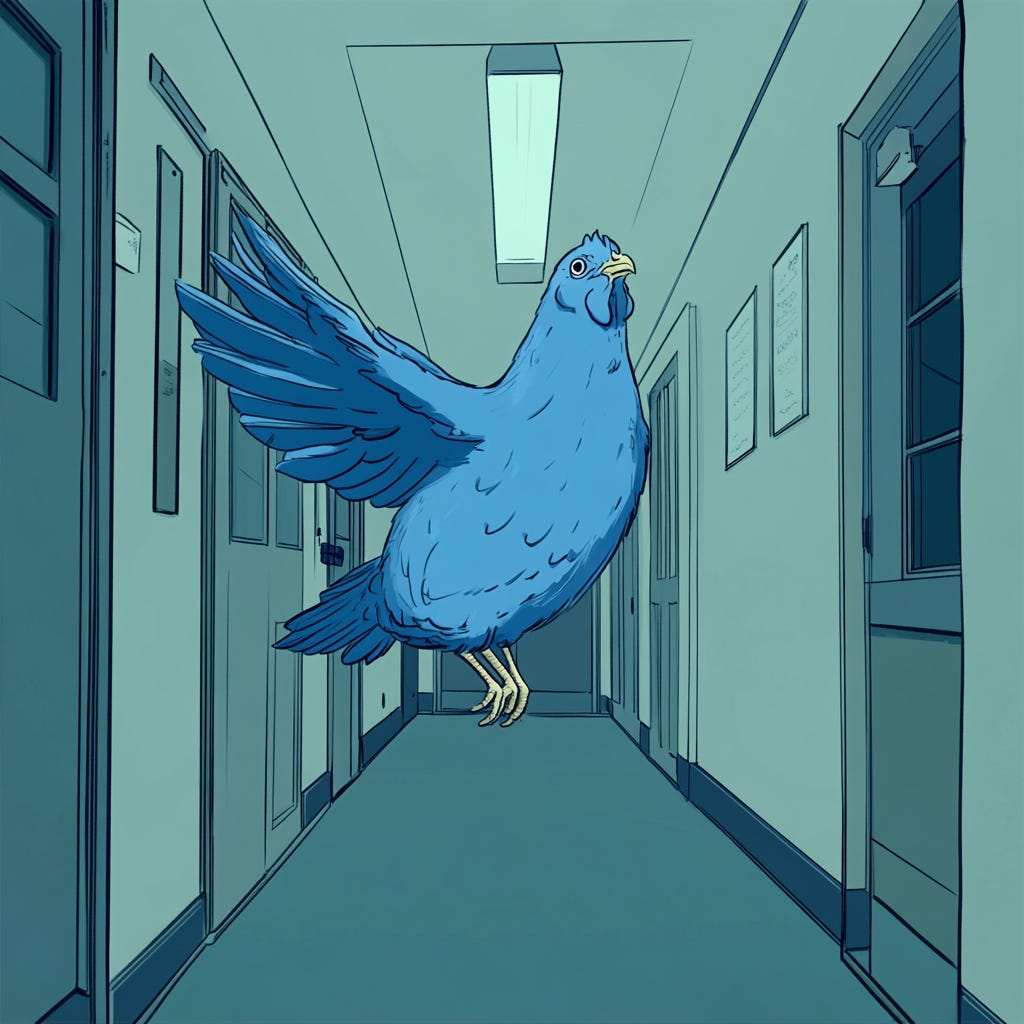

One day an anonymous student hung a dead, de-feathered chicken, painted electric blue with some kind of enamel paint that made it look radioactive. No one knew who did it, and there was a debate among my classmates about the provocative piece. They all hated it and thought it was disgusting and stupid. But as the debate (held mostly in Catalan, which made it hard for me to fully participate in it) progressed, I felt I disagreed. I told them: you may hate that piece now, but what you can’t deny is that it is memorable. I bet you that thirty years from now you will have forgotten all the paintings that we have in the classrooms around us, but that blue chicken is something you are not going to forget. They all dismissed my comment as ridiculous.

I have lost touch with all of my ex-classmates, so I am unable to verify my claim and I can’t be the judge of my own bet, but I certainly have not forgotten about the blue chicken, while I have honestly forgotten all those Tàpies and Miró imitations in class. If anything, the incident continues to inform my mind about the resolution we demand about art works, and how some of the best ones, ensure to never give it to us entirely, but at the same time engage us just enough, like a riddle, so that we do not give up thinking about it. It straddles the fine cognitive dissonance line, in that it is not too intimidating for us to run away from it, but also not safe enough for us to altogether disregard it as a mere artistic prank. And it is healthy, I believe, for it to be so: each one of us should all have a blue chicken, a pollastre blau, always hanging in our mind.