For Jordi Sod

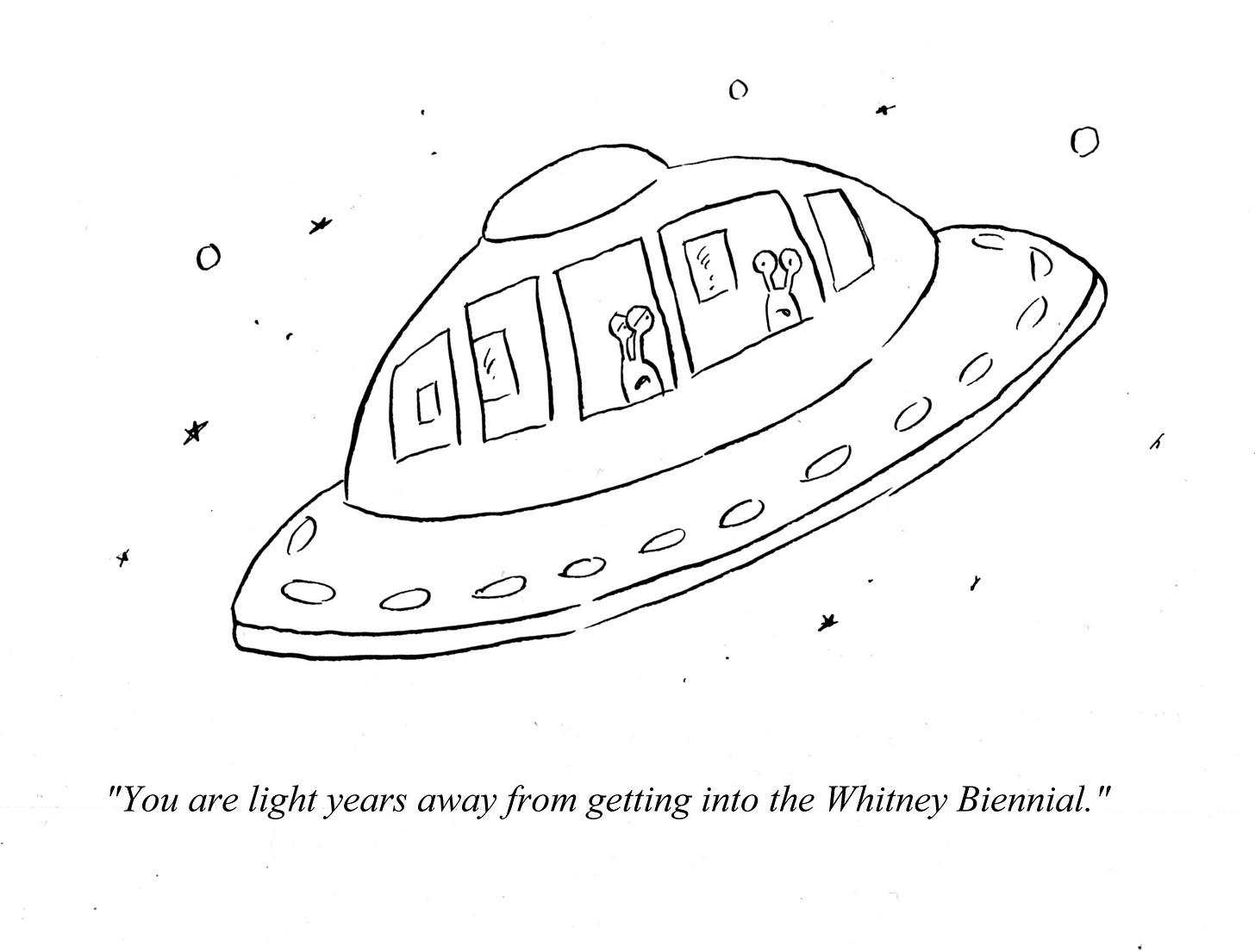

A few years ago, I wrote a post on Facebook that caused a bit of a stir: “I have never seen someone opening a physics book and declaring ‘this is not physics’, yet I see people walking all the time into galleries and confidently say ‘this is not art’.

Almost immediately some people objected to my comparison. One rightfully replied that there are indeed people who openly say that some scientific facts are not science (anti-mask wearers today come to mind). Others felt that the analogy was unfair. My point, in any case, was there is an implicit expectation that great art connects with us in such a human way that we don’t need mediation to process it, while we know that science is just too hard to understand if we are not scientists, and that it is, as the dictionary describes it, “the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment.”

Over the years my thoughts have recently gravitated to the question of why is it that in the world of science there have been prominent thinkers who have led in their field but also have been great popularizers of the discipline, such as Stephen Hawking or Richard Feynman in physics. In contrast, it is difficult to point to a leading thinker in art theory who took upon themselves to project their ideas to a very wide public. Arthur Danto comes closest in my mind, as he was such a compelling and clear writer, but I doubt his books ever managed to match the 10 million sold copies of A Brief History of Time.

I don’t want to go into the rabbit hole-topic of the promotion of the art practice itself, which would force me to write about Bob Ross. In the broader visual arts category (not art theory but art history and art criticism), the figures who have become great popularizers of the form become TV stars (such as Sister Wendy Beckett) or social media/reality show personalities such as Jerry Saltz. Saltz’s ubiquity in social media and in news media in general makes him central to the question on if/how we can make contemporary art compelling to a wider non-specialist audience. But despite the fact that he has won a Pulitzer prize in journalism, he does not occupy an enviable role before the arts intelligentsia: in 2015, curator Robert Storr gave an interview where he made scathing comments about Saltz calling him “appalling” and the “class clown”.

The truth of the matter is that Jerry’s comments and stories, whether you might find them endearing, entertaining, irritating, or all of the above, are largely external to the discussions that many of us in the art practice have amongst ourselves, which truly are not intended to appeal to the broader public, but are rather to attend to specific to issues related to the art practice that are too specific for someone who does not have to confront those issues from the theoretical or practical standpoint. I don’t think people who are not artists are too interested in hearing me talk about appropriation, intertextuality, deskilling, parafiction, or intentionality— topics that I am passionate about, central to my art practice and which I always need to discuss with others, but I don’t expect Miss Lee, the deli owner next door to my house, to care much about (nor do I feel the urge to go downstairs right now to try to explain any of these things to her). I also have very different conversations (in Spanish) with my peers in Mexico and other places in Latin America about political and social issues that impact and pertain to the art practice there, and which would likely be unbearably boring and useless to the non-artist.

It seemed important to me to understand how the model of dissemination of knowledge operates in science (and I acknowledge being a total layperson in that field). I thus corresponded with Sergio de Régules, a Mexican physicist and prolific writer who has authored many books (he identifies himself as a “scientific writer”) and someone who once curated an exhibition about the relationship between science and art. De Régules reminded me of other notable cases of scientists who also performed the role of promoters of science. One is Stephen Jay Gould in paleontology, (who was such an eloquent and elegant writer, and whose encyclopedic knowledge, by the way, allowed him to effortlessly engage in discussions about art with those of us in the field). The other example is Carl Sagan in astronomy, who was hugely successful with this series “Cosmos”. De Régules writes: “The model is common in the United States and Europe. There is another model that functions excellently well: the promoter who is not necessarily a scientific researcher… it is the case of a really high proportion of great international promoters who can be journalists or scientific writers.”

But De Régules recognizes a possible parallel with the art world:

“In the world of science, just as in art, the activity of public education/promotion of science is not well looked upon. Promotion is largely seen as a second-rate activity, like a waste of time, such as dirtying your hands by throwing daisies to the pigs. Carl Sagan was treated very poorly due to the success he had.”

And science is not exempt from elitism either. De Régules concludes: “Physicists are elitists, but in another way. In science it is crucial that everyone should speak openly of what they know and how they know it. Transparency is valued more than in any other discipline, because without it you waste time and resources reinventing the wheel. That said, there can be secrets and espionage; for instance, amongst groups that compete in fields where there might be money or possibly Nobel prizes, and especially if the group is working for the private sector and not for a public research institution. Elitism amongst physicists lies in thinking of oneself as a scientist amongst scientists (which is mistaken but common). And of course, no one despises a promoter more than one of those physicists.”

Is there something thus to be learned by the art world from the world of science in this regard? If pressed to summarize, I would perhaps suggest two points: if intellectual curiosity and the creative impulse produce knowledge, we should celebrate those who have pursued it, and not condemn those who have worked to attain it as elitists ( relatedly, it is important to recognize the difference between specialized knowledge and the artificial status attained by resources like money and social and racial privilege. Because art making is so intertwined with the hierarchies of the art market, we often fail to separate them.)

The second point is that the status anxiety generated by the need to have insider knowledge is not exclusive to the art world. This might explain (or not) the skepticism toward those who want to spread the gospel of a particular topic (be it the cosmos or conceptual art) to the world. But the widening of knowledge only makes us richer, not poorer. And you can still keep your subscription to October or Semiotext(e) and be confident that no one will come take it away from you, or make you feel less special. Believe it or not, what makes you unique is your own ideas, not the repetition of the ideas of others— whether they are about quantum physics theory or zombie formalism.

Art theory is not followed outside of its discipline much. Art is another matter. Indeed John Berger, Henri Focillon and even Gombrich who made aspects of art and art history accessible to many come to mind. Are you making a distinction between Art and Art theory?