Arlington Heights, IL

As a young child— in maybe a foreshadowing of how I would be drawn to the visual arts— my brain would make all sorts of odd image associations with words. For example the word “iglesia” (church) I thought was spelled “inglesia” (a mixture of the word “inglés” (English) and “iglesia”). So as a child I thought that “Inglesia” was the name for the country “England” (not the correct name “Inglaterra”) and I further imagined it to be a country full of churches (which I suppose you could argue that it is).

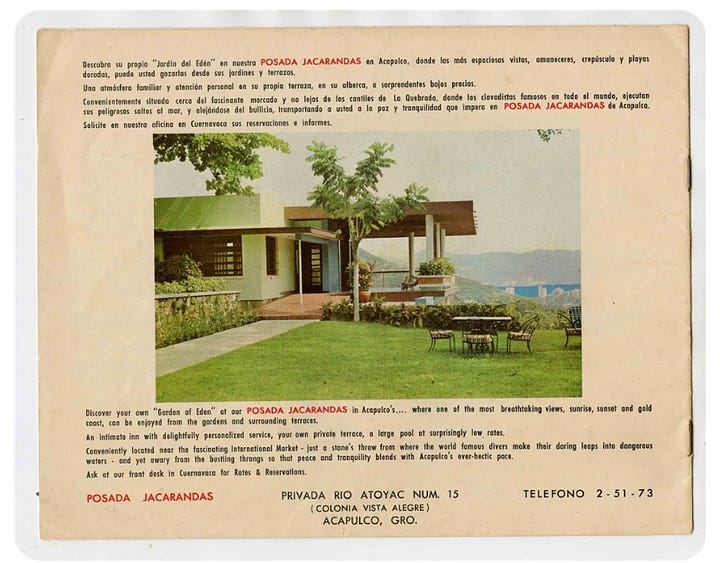

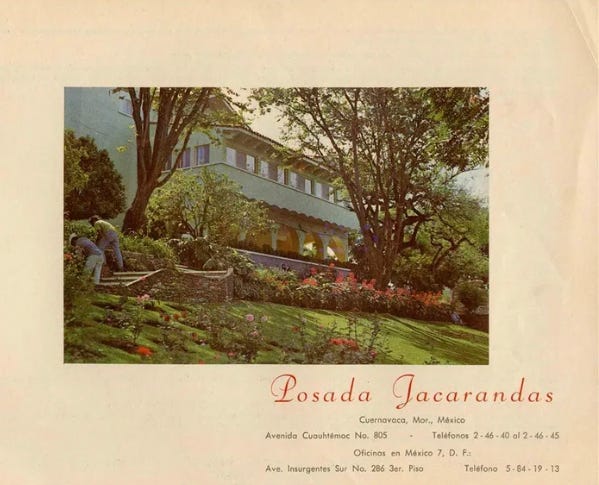

Similarly, the term “vacación” ( or “vacation”, which is something I am trying to have this week, thus the subject) also sparked positive images in my mind with a subconscious complexity of their own. In my case I associated the word with three images: first, I envisioned the florid gateway of the city of Cuernavaca (connecting the words “vaca” from “vacación” with “Cuernavaca”), a traditional weekend getaway an hour away from Mexico City, known as “la ciudad de la eterna primavera” (“The City of the Eternal Spring”) because of its warm climate and lush vegetation. Cuernavaca was a place that my family would often go for vacations since it was close to the city and it was a relatively inexpensive getaway. The second image involved the word association with the term “vaca” (from the link between “vacación” /“vaca” -cow) and the sign of the fast food restaurant La vaca negra (the Mexican version of Tastee Freez), which featured a sign with a happy animated/bouncing black cow. Opened in 1957 in Acapulco and then in Mexico City, in the 70s and 80s it was the only place in pre-NAFTA Mexico where you could have root beer. Aside from the fact that I visited the Acapulco branch as a kid, going to La vaca negra to me must have felt like being on a holiday, so the word “vacación” prompted that image of that bouncing, happy cow. Last but not least, the third image that represented the term “vacación” to me was the hotel in Cuernavaca that we frequented during those years, Hotel Posada Jacarandas.

It was incredibly exciting to me when our car entered the long main driveway of Jacarandas, which was covered with trees and vegetation— a long green tunnel that would lead to the main building.

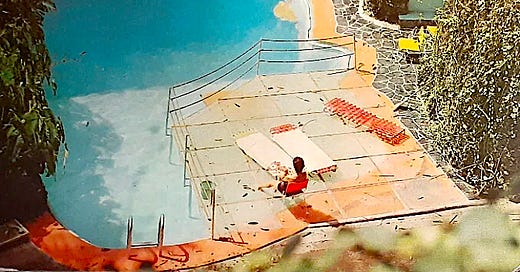

The hotel Jacarandas must have been built sometime around the late 50s or early 60s. Its layout was one of bungalow-style rooms, common at the time, distributed in around 9 sections, each built around a large garden and a swimming pool at the center (it was in one of those many swimming pools where I learned to swim as a child). A big attraction was the large swimming pool known as “La Poza” located on a deep pit surrounded by volcanic rock and a poolside bar where my aunt would order Congas and White Russians. The complex had 30,000 square meters mostly consisting of carefully manicured gardens and included tennis and squash courts. It offered luxurious suites, one made in Japanese style, another that was built as a treehouse for newlyweds (El nido del amor). I remember hearing that they had an army of 50 or so gardeners who took care of the vast property.

Over the decades, Jacarandas suffered a gradual and steady decline. Like the faded family photos and slides that we have of those sunny days, the hotel complex only retained similarly faded remnants of its former glory; yet we continued going there as a family, the last time being in 1997. In spite of its aging buildings and its partial state of neglect, the place continued being to us some kind of nostalgic shrine where in almost every corner where we had built family memories, frozen in home movies.

As I was trying to gather more information about this hotel this week, I learned that Jacarandas finally closed for good in February 2023 and is in the process of being transformed into a private apartment complex. This might sound absurd, but I was deeply saddened by this news, as if a close relative had passed away.

It’s a sadness full of contradictions of which I have been trying to make sense. I have been trying to figure out if it is just silliness from my part or if it connects to something larger.

I would like to think that most families have a favorite go-to spot over the years — the beach, the countryside, the lake, the mountains; a place that over time became an important setting for happy memories that would make their way into a photo album. The paradox of those places, if you have ever had them in your life, is that they are special precisely because they are transient— but at the same time it becomes important that these settings remain, or at least feel, the same every time you visit them.

So why this need of permanence within transience? In the brand management world it is clearly understood that consumers believe that their choices for a product stem from a rational process— such as considerations of price, quality of product, etc. But in reality the consumer-brand relationship is a much more emotional and personal one (this is something about which I have written before vis a vis the museum visitor experience). This is the basis for what is known as “Nostalgia Marketing” : Brands make products that appeal to a particular group of people who might subconsciously want to recreate, through the purchase of the item, certain feelings or memories. I observe this in my local drug store where there is a section of “ethnic” products— meaning, products that are popular in the countries of origin of some immigrants. Rite Aid sells Heno de Pravia and Maja soaps, two products that are popular (and considered fancy by some) in Mexico but that I doubt have much of a market, if any, outside of the immigrant population. In the case of the immigrant, the individual is the one who is transient; so one gravitates toward products that are familiar, consistently the same: they give us a sense of grounding and of self.

So in this sense hotels and resorts do become that kind of gradual repository of emotions that accumulate through every transient stay over the years when one becomes a “regular”. And, given the general positive nature of the experiences in those places, they slowly become family history sites, or, in mnemonic terms, loci (physical spaces where one mentally places specific memories). This fact makes the personal desire for places like that to remain exactly the same forever. A friend of mine who also shared a similar family relationship with Hotel Jacarandas once told me that, more than a hotel to her, Jacarandas was “a state of mind.”

That constant search for attaining a particular state of mind, or desire for a predictable experience, was definitely part of my family’s relationship with this hotel. But while my family lamented the news of its closure they didn’t seem as affected as me, so I realized that in my case my reaction did not have to do with my attachment to nostalgia marketing but to something deeper.

It is, I concluded, my psychological conditioning and disposition toward change: intellectually it has always been clear to me that clinging to the status quo and the aversion to change are harmful and paralyzing impulses, particularly in art making. At the same time I have always felt that it is difficult to pursue uncertain paths if there are no constants in our life – for instance, if our personal life is mayhem, if there are no dependable systems of support to rely on, we can’t tolerate, or successfully sustain, mayhem in the art process; in other words experimentation requires an ingredient of predictability. That hotel in Cuernavaca, frozen in time and even in that decayed form, represented in a small way a dose of predictability that I needed to know existed out there in the world even if I were to never return to it. But now it is gone and I now will have to go through my own personal mourning process of that little component of my life.

Back in 2016, intuitively sensing the eventual demise of this hotel, as part of an exhibition I did at La Tallera (a contemporary art space in Cuernavaca that used to be Siqueiros’ studio), I created an installation piece there that consisted in recreating a room from the Hotel Jacarandas (in fact we asked the hotel to let us borrow/rent a few items from its mid-century furniture).

Art making sometimes functions as an instinctive, restorative impulse in response to death: it becomes an auxiliary force to seek to recover, in some way, symbolically or otherwise, something that we feel we have lost.

I sign off still trying to reconstruct the images and sensations offered by the word “Jacarandas”: a melding of the distant sounds of children playing in a swimming pool, the faint smell of chlorine mixed with suntan lotion; the texture of colorful towels for rental by the poolside the rumor of washing dishes from the restaurant, the purple Jacaranda flowers and the bushes with miniature apples or manzanitas (Pyracantha coccinea ) that as children we were always warned not to eat because they were supposedly poisonous like Snow White’s apple; the all-enveloping chirping of crickets at night; the outdoor lights of the hotel terraces illuminating the corners of the loci of this, like many other — increasingly accumulating and as we grow older— defunct states of mind.