During the Covid-19 pandemic in New York City, the city allowed restaurants to build outdoor sheds to offer al fresco dining and help prevent the spread of the virus. It was a welcome relief to finally leave the house and enjoy a meal outdoors, especially as the weather grew warmer. The shed next door to our home belonged to a Mexican restaurant, painted in a soft shade of green. Looking back, it seems almost trivial, but the shed’s distant, shoddy and vague evocation of Mexico made me feel both closer to and farther from the country than ever before. It was a peculiar kind of melancholia, perhaps stirred by the isolation that had pushed us into a period of deep introspection, reliving personal memories—an emotional state that this little evocative space seemed to amplify.

I thought about this again a couple of weeks ago when I attended the opening of the exhibition by Rubén Ortiz-Torres, titled “Zonas de Colaboración”, at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery in New York. Ortiz-Torres, who was born and grew up in Mexico City, is based in Los Angeles, where he has lived since 1990. I share in some ways his binational journey (as I also emigrated from Mexico to the US around that time), as well as his ironic and critical outlook about the world, which at times verges on the anthropological and often contains an element of irony and even sarcasm. We also share a musical background— although Rubén comes from Mexican musical royalty, with his parents having been two of the founders of the group Los Folkloristas and his sister, Gabriela Ortiz, is a Grammy-winning contemporary composer. I have always admired his ability to engage with urban pop culture and its many idiosyncrasies and syncretisms, ranging from baseball to rock and lowrider culture, which he describes as a “form of resistance”.

In the exhibition, which includes a number of pieces that bear his very own brand of postmodern irony and engagement with underground border culture, I encountered for the first time a series of photographs he had made around his first visit to Machu Picchu which, in my view, had a very different character. The photos are palladium prints, which is a type of photographic printing that involves palladium salts instead of platinum, which is the more common (but more costly) technique. Palladium prints were introduced in the 1910s and commonly used until the 1930s. I quote the description of the works in the exhibition:

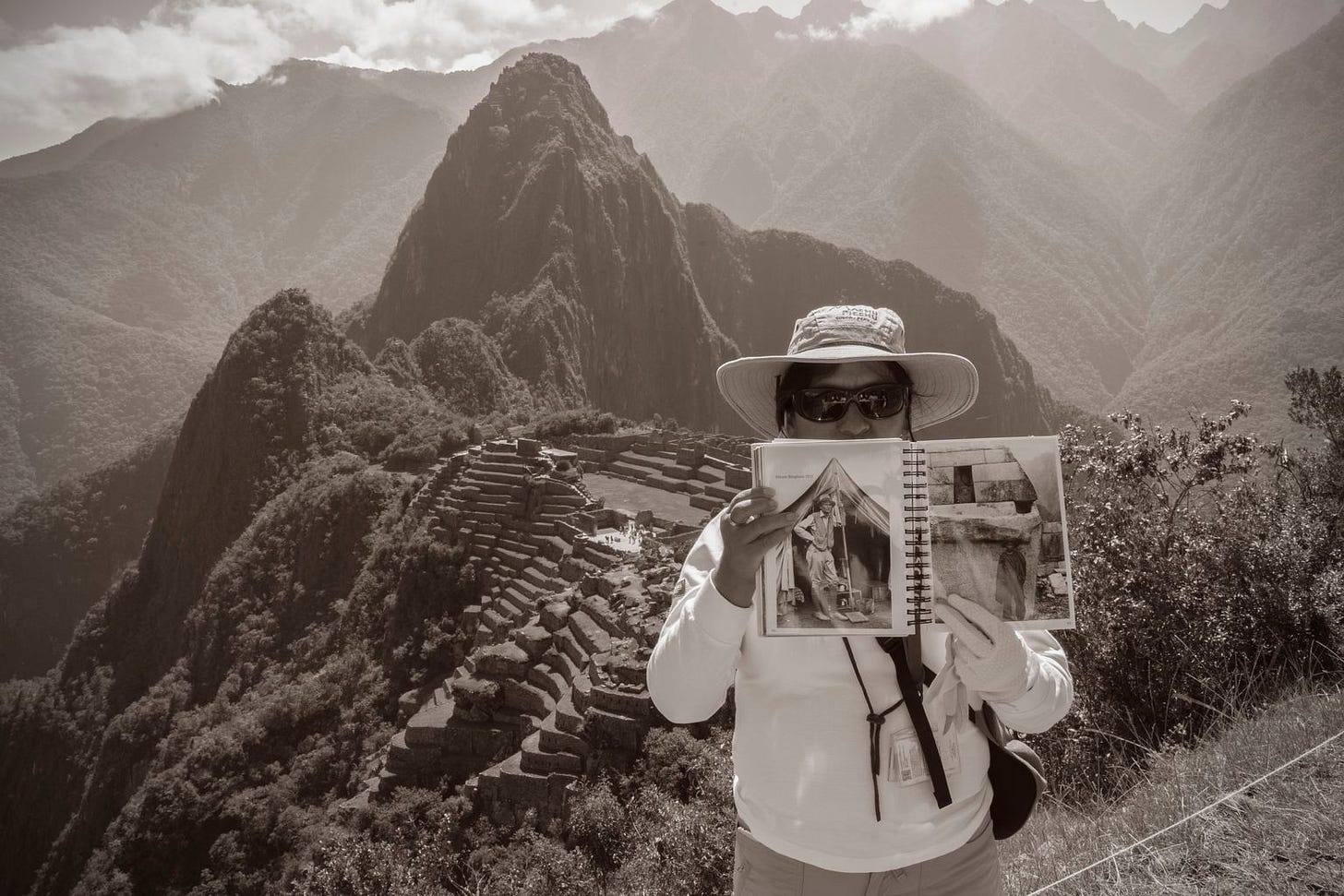

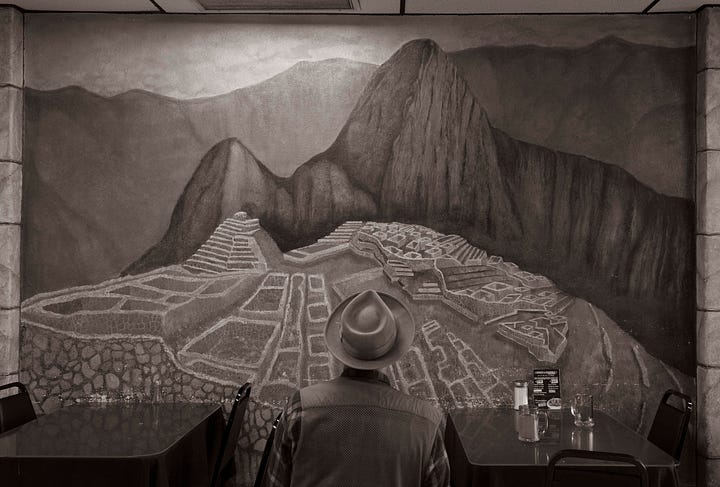

In a singular palladium print showing Rubén Ortiz-Torres’s visit to Machu Picchu his guide holds up a booklet with two photographs—one of the American explorer, Hiram Bingham, the first photographer of the site, and the other of a local child guide—while the tour group looks towards the ancient site. Another print of a diorama taken at Museo Casa Concha at Machu Picchu is a simulacra of Bingham photographing a worker excavating a cave burial. Ten additional prints feature images of murals of Machu Picchu in Peruvian restaurants in Southern California. Each of these restaurants positions the iconic ancient site, a 15th-century Inca citadel located in the Eastern Cordillera of southern Peru, as a backdrop to the intersection of culinary experiences, social spaces, and dislocation.

Speaking to Rubén about these works, he remarked on the peculiarity of the fact that you can only photograph the site from one angle if you want it to be readable as Machu Picchu, starting with the very first photograph that Bingham took when he encountered (and, controversially, “discovered”) the site in 1911. In his words, “the architecture is not particularly iconic and is similar to other Incan ruins so that someone without knowledge of the place would not otherwise recognize it without the landscape. Hiran Bingham did not discover the place that was known locally and even a family lived there, but he did take the first photos including the first of the shot that we recognize as Machu Picchu.” Also, as National Geographic photographer Jim Richardson recently wrote, “Nobody takes a bad picture at Machu Picchu. But then we all take almost the same picture that Hiram Bingham shot with his Kodak 3-A Special all those years ago.”

I also found it interesting that those Peruvian restaurants that Rubén documented, which contained those evocative images of Machu Picchu, turned out to be way more transient and fragile than the archaeological site itself: “There is one I went to called Mamita that had a large mural photo of Machu Picchu. However, now that Peruvian food has become more recognized, [the restaurant] became gentrified and the decoration was changed to a more generic modernism. So, I had to rush to document these restaurants that still serve a more immigrant clientele where we can still find “Machu Picchus” before they gentrified and started charging more for smaller and more minimalist portions and changed their decoration.”

The photographs operate in a variety of ways. First, they offer a meditation of sorts of both the monolithic aspect of the register (i.e. you can only see the site from that same angle) and the variations of representation, ranging from the claiming of the image by the white explorer to the reproduction of that image in Peruvian restaurants in Southern California. And last but not least, they enter into the long genealogy of the practice of reassembling the self through familiar imagery and iconography, what is known as cultural reclamation or diasporic cultural reconstruction. The spiritual vacuum created by the immigrant experience makes one try to piece back together the fragmented self with images that represent the collective cultural experience. Machu Picchu is emblematic (and arguably an irreplaceable image) of Peruvian identity and heritage, which is why it is logical to encounter it in a Peruvian restaurant.

In 1974, the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan used the term "topophilia" to describe a deep emotional connection to particular places or landscapes. While this term is not strictly about "topographic memory," per se, it reflects the strong relationship people have with places that can shape memory and identity, encompassing both physical and emotional aspects of landscapes. What has always been most interesting to me is how these fanciful interpretations that often depart (by idealization, slight aggrandizement, colorfulness etc.) from the original often feel more authentic to the immigrant than the original thing, a concept that was articulated in 1983 by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger in the book “The Invention of Tradition”. I felt that Rubén, with his aesthetic and sensitivity, was attracted to this type of contrived representation (as I happen to be as well). I also sensed a contrast in his usual humor and irony with this series, which feels more reflexive, and perhaps more meditative, than his other works. I presented my impressions to him in order to get his thoughts:

“This series is related to photographs I took of “fake” ruins also using ancient processes in unexpected or contradictory places such as Spain, Japan or the United States. There is a list of that portfolio that I titled “The past is not what it was” with photographs that Lourdes Grobet took of modern interpretations of ruins in Mexico. In Grobet's case, these respond to an architectural nationalism and in mine more to a reverse traveler's photography in which instead of a European photographer going to Mexico or the promised land in search of these monuments, I had to go to Benidorm or Las Vegas in search of their replicas. The photos were funny and fun and I suppose they had that “humor and criticism” that you refer to, reversing the colonialist documentary enterprise of archaeologists who were also spies like Désiré Charnay. I thought there would be something similar in these photos in relation to Bingham and certain absurdities such as including the sepia diorama of him photographing, but when I see the images of the Peruvian restaurants in Orange County and Hollywood and remember the ceviche I ate with chicha morada I feel more respect and admiration than humor and in this sense it turned out different.”

Certainly, Ruben’s most postmodernist (and a true-to-form ironic) touch in the series is the image of the tour guide holding the book with a photo of a diorama at a Peruvian museum depicting Bingham — a dizzying photograph of the photographer who photographed the site and now has become an integrated “artifact” of the site as well as a character in the complex web of relationships of the gaze, perception, knowledge and power, kind of how Velazquez’s Las Meninas functions.

But just like it works in that painting, ultimately the reflection bounces back to us, the viewers, making us examine the way in which we create and live by our own personal mythologies. I certainly thought back to that light green shed of the Mexican restaurant next door to my house, which by the way was finally torn down a few weeks ago per demand of city regulations. I now wish I had made a palladium print of that rickety structure.