“Don't you love New York in the fall? It makes me want to buy school supplies. I would send you a bouquet of newly sharpened pencils if I knew your name and address.” This sappy Nora Ephron phrase from the romcom “You’ve Got Mail”, often comes to my mind during this time of year. Sappiness aside, the increasingly crisp weather invites study and dedication, and psychological studies have shown that the autumn season offers the opportunity to do new clear thinking, resuming a more structured routine, and focus less on physical appearance (wearing more layers and avoiding the focus on our less than beach-ready bodies).

In my case, my affection for the fall is tempered this year by the fact that I am about to enter the busiest period of my life ever— teaching four days a week, working toward a deadline for two books and opening four solo exhibitions (plus a fifth one that is a three-artist museum show). My schedule has now become close to a surgical operation with little to no room for error, acts of god or missed flights (or of forgetting my passport at home, as I recently did during a 5am check-in at Newark). Demanding calendar situations like these are increasingly problematic by the inversely proportional effect of growing older and seeing one’s energy decrease. All I can do is to use my experience (as we say in Spanish, “más sabe el diablo por viejo que por diablo”), so rather than spend extra energy to compensate for poor planning, I have to put my experience into very precise scheduling of both production and planning resources. Still, and partially because of the fact that my challenges are more of a scheduling nature, my main concern these days is no longer about what I am supposed to do, but how much time I have to properly plan and develop it and how to deliver it on time.

Needless to say, I am not even close to being the busiest person in the art world nor would I care to compete for the title. I am often astonished at the number of things that Hans Ulrich Obrist does (successfully, I might add) and his drive for doing them. Per his own telling, he takes catnaps every three hours and only sleeps 5 hours a night: “I don't like to sleep more because of time constraints. Sleeping is good, but there is so much else to do.”

I am also fully aware that being busy (in art as in anything else) is more a status symbol than an indicator of substance. In the art world we want to at least create the impression that we are in demand, for the more we are (or pretend to be), demand is likely to increase. The predictable downsides are that doing too much greatly diminishes the quality of our output and/or generates the impression that we have a same solution to everything. Sometimes with the very famous this doesn’t even matter that much. I remember Vito Acconci’s artist lectures (who was always in demand to give them), which he gave with the exact same slides of 30 years before, speaking almost with the same exact phrases and stories about every single one. I did see him give the exact same presentation about three times, but I didn’t mind it. It was like going to the opera: you know the music and the story; you are there for the interpretation and to relive the experience.

I have worked for my entire adult life since I was 18, and in fact it is rare for me not to be working in some way every single day (whether writing, making art or doing education work). I once was told by a Mexican curator that I had a “protestant work ethic”; the comment made me uncomfortable. I concluded that given that I joined the American work force at 18 I inevitably did have to absorb and learn its ethos in in the Capitalist /Max Weber sense, but in reality and more than the influence of the US or protestantism, the example I instinctively followed was from my father, of whom I believe I unconsciously and always sought to fill in the mold and who was one of the hardest working persons I ever knew.

Furthermore, I have always believed that to the practicing artist every day is a workday; this is to mean that art making is usually less about revenue-generation and more about the simple desire and drive to make. And because the opportunity to present what we make is so stimulating and addictive when it comes, we often bite more than we can chew. Thus we become overscheduled.

As I begun to write about this I thought of Michael Mandiberg, a friend and artist who once told me that I was the only person they knew who was busier than them. Asking them further about this, Mandiberg, who also was the creator and director of the New York Arts Practicum (a summer arts program where participants experientially learned to bridge their lives as art students into lives as artists in the world) mentioned how they encouraged the participants to reflect on how artists manage themselves and pay attention to the distinction, in Mandiberg’s words, “between people who juggle time and people who juggle money. I put forward that there was a continuum between artists who are inclined to accept uncertainty over limited creative time in exchange for a greater degree of certainty over a more stable amount of money and artists who prefer to have certainty over are larger amount of creative time in exchange for less financial certainty/stability.” How an artist addresses this balance, in Mandiberg’s view, has to do with personality, “but it is also about aptitude: I have always had an aptitude for planning and have learned to build organizational systems. I like integrating younger artists, designers, programmers, and thinkers into my studio practice in an apprentice/assistant role—it is where the New York Arts Practicum came from, and it is also helps integrate my creative and pedagogical lives.”

Mandiberg’s reflections made me also think about how overscheduling, which might be at times be criticized as workaholism or as a form of psychological hoarding, whether it is a necessity to keep up with the rat race of the art world or preventing an oversized FOMO, are realities that we as artists sometimes channel into our own creative language: we turn that scheduling ritual into art works.

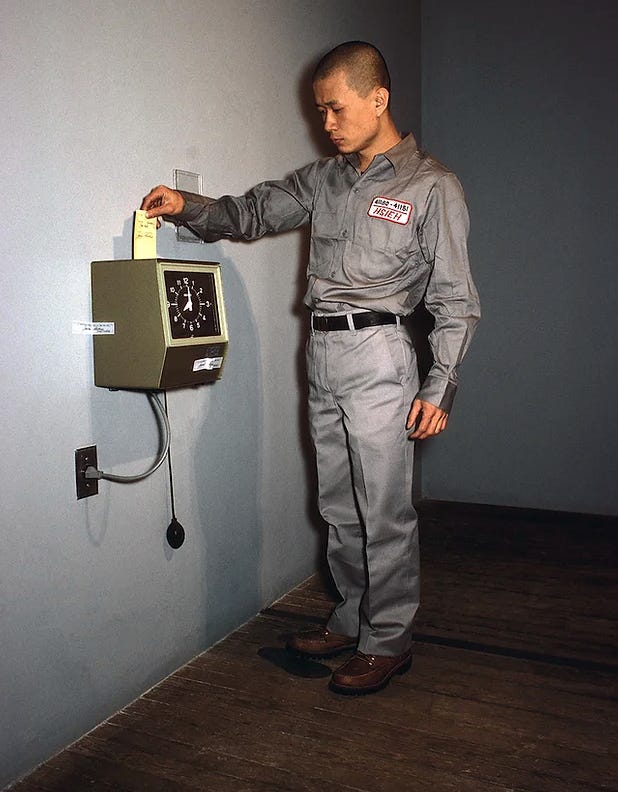

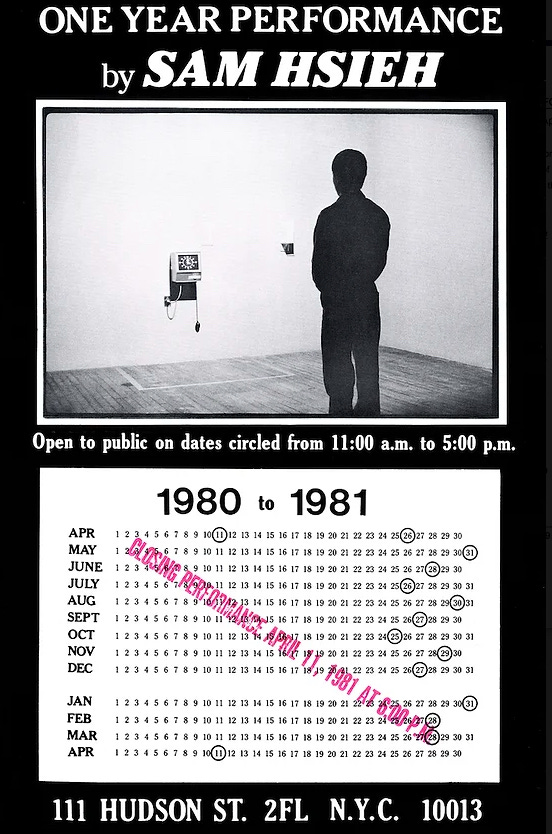

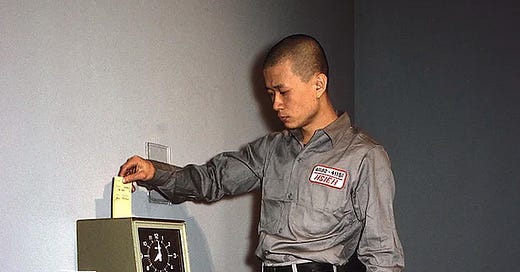

There are three (of many) variations of that concept that immediately come to mind. The first is the work of the scheduling as art master, Tehching Hsieh, in particular his One Year Performance (1980-81) where he punched a time card every hour on the hour for one year.

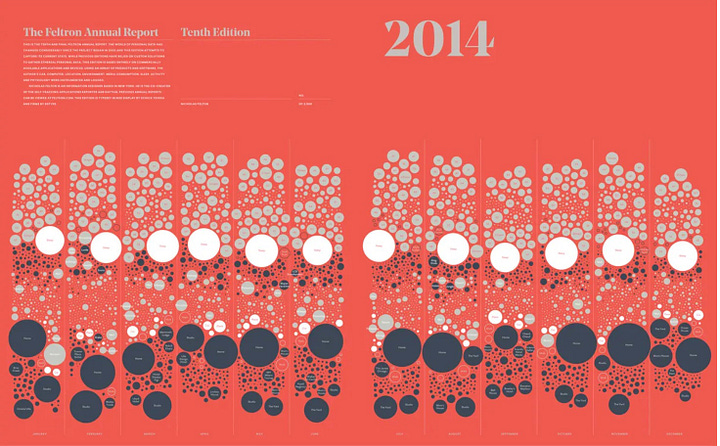

The second is infographic designer Nicholas Felton, who has in the past described his work as "translating quotidian data into meaningful objects and experiences". Between 2005 and 2014 Felton developed the Feltron Project, a project consisting in documenting all his daily activities over the course of a year into a series of graphics, showing us things like how many hours he spent at home vs. studio, his sleep patterns, the amount of time he spent driving, listening to music, being on the computer, and so forth— kind of a precursor project to the Fitbit or Apple watch, albeit on steroids. Precisely perhaps because of the increased ubiquity of these forms of self-quantified measurements, Felton concluded this project. It remains, however, a wonderful work that reflects on the poetics of existence all derived from measurements. I would have loved for Henri Bergson to meet Felton simply to reflect on how a project like this would be understood according to his ideas of duration and measurement (Bergson was a critic of quantified measurements as he saw them as poor ways to comprehend inner life).

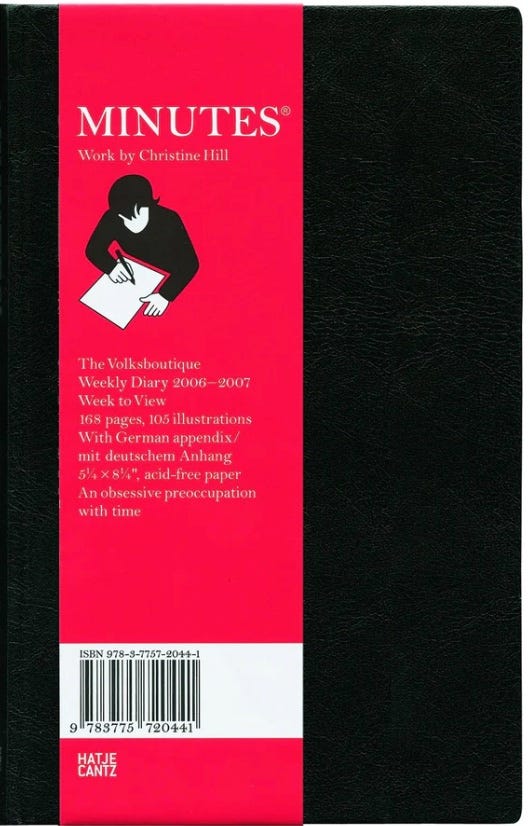

Yet one of my favorite projects in this regard is by the Berlin-based artist Christine Hill, creator of Volksboutique and master scheduler herself. In 2007, Hill published “Minutes: Work by Christine Hill: the Volksboutique Weekly Diary” — a catalogue of sorts for a project she exhibited at the Venice Biennial Arsenale. The publication, which resembles a Moleskine appointment calendar is a facsimile publication of Hill’s own personal calendar for that year. Hill is a painstaking organizer who specifically annotates every appointment and meeting she has, and the calendar in question comprises from March 2006 to March 2007, including project deadlines, work meetings (I even remember finding my own name in the calendar, on a day when we met for coffee in New York) and even beauty salon appointments.

Projects like these exemplify how conceptual art can help us make sense of our (perhaps intentionally) overscheduled lives. I am trying to learn from them (although I am afraid that reflecting on that is yet one more thing I need to add to my schedule).

However, we can’t all transform our overscheduled life into an artwork— in addition of it being impractical, it would also likely not be such an interesting artwork anyway. So we are often left with an overpopulated schedule that we hope to enhance our status when in fact it likely is more a means of deterrence of self-reflection: we often make ourselves busy because we fear the productive silence that accompanies introspection. And using new age self-help books to solve this problem might be embarrassing. We need a model that might give meaning to a method of living— not necessarily of someone who practiced overscheduling like us, but someone who knew how to meaningfully use their time.

One such model to me is Immanuel Kant. As it is well known, the Prussian philosopher was only 5 feet tall, had a deformed chest and frail health; because of his heightened awareness that his health was so fragile and his life likely limited, he followed an intensely rigorous health regime which included walking like clockwork through Königsberg at a very specific time of day, rain or shine. He did it with such daily precision that his neighbors would adjust the watches whenever Herr Kant passed by. On another occasion, the legend goes, once that Kant’s grandfather clock at home had stopped after not being wound up, and given that Kant knew exactly the amount of time it took him to walk back and forth from his friend’s house to his own, after checking his friend’s living room grandfather clock and returning home he was able to calculate the length of time he had spent in going back and forth plus the time spent at his friend’s house and reset his own clock to the correct time. You can argue that Kant was an early experimenter of self-quantification.

By implementing his methodical thinking to his life, Kant lived to the ripe old age of 79 (a truly ancient age in the 18th century). Which proves that against all odds, we are ultimately measured in our lives (as artists, philosophers, or just regular mortals) according to how we harness time. Or, to end with a (fallacious, but still true) syllogism merging the equally essential Ecclesiastes and Miles Davis:

1.For everything there is a season.

2. Time isn’t the main thing, but it is the only thing.

3. Ergo, scheduling is the main and only season.

I suggest making a note of it in your Moleskin calendar using your bouquet of newly sharpened pencils.

Tehching Tsieh's work is one of those that make you re-evaluate your life and that stay with you forever...

Before knowing him I had done a couple year-long projects:

"You Are What You Eat"- photos of everything I ate during a year, before cellphone cameras ruined dining experiences.

"You Are What You Wear" - a different white t-shirt each day, with the date printed on.

"Subway Reading" - where in the last days of December I bought a copy of the book I had seen someone on the subway reading, and on January I started reading it on my commute to work. Before finishing it, I started looking for someone else reading, took note of that book, and bought and read it. I ended reading 19 books...

For the food project, at the end, seeing everything I ate, we noticed how bad it was, even though there was practically no fast-food anything in it, and changed our diets.

For the t-shirts, it was so liberating not having to decide what to wear. I'm a man, so for me t-shirt and jeans is enough, but having to dress up according to the planned activities of the day is a pain...

And for the subway reading, it's sad that you now barely see anybody with a book. And now that I work from home, I do miss the couple hours that I could read without interruptions...

"Plans are what we do to make God laugh"

(don't know who said it, but it's been a mantra for me for many years...)