From your Lips to the Art God's Ears

Strategic intimacy in exhibition-making.

Tamás Szentjóby and Gábor Altorjay, “Lunch (in Memoriam Batu Khan), the First Happening in Hungary”, June 25, 1966 (with the cooperation of Miklós Jankovics and István Varannai, Enikő Balla, Miklós Erdély, and Csaba Koncz)

Last week I received an email from Alena Marchak from Marian Goodman Gallery on behalf of Gabriel Orozco, inviting me to a show he had put together in an impromptu basis. Orozco by chance had seen an empty gallery space in their building (formerly Francis Naumann’s Gallery, which specialized in Surrealism, Dada and other artists from that period) and decided to do an intervention of sorts, installing old and new works of his, and titling it “Spacetime”. His instinct was to set up a wunderkammer-type of space, bringing together works he has made since about 1992, which are meant to be encountered in a spontaneous way by visitors. The display will be there for eight months to a year.

What really drew my attention was the end of the email, where Alena wrote: “The show is also unique in that we have not made any official announcement of it. Gabriel wanted the show to be known to people only through word of mouth, and serendipitous visits.”

I decided to contact Orozco to better understand his motivation behind the “word-of-mouth” aspect of the exhibition. “It’s like a semi-underground exhibition”, he told me. “It is as if you wandered into a strange situation in a party, like striking a conversation with the party-crasher. It is like wandering into my studio, my library.”

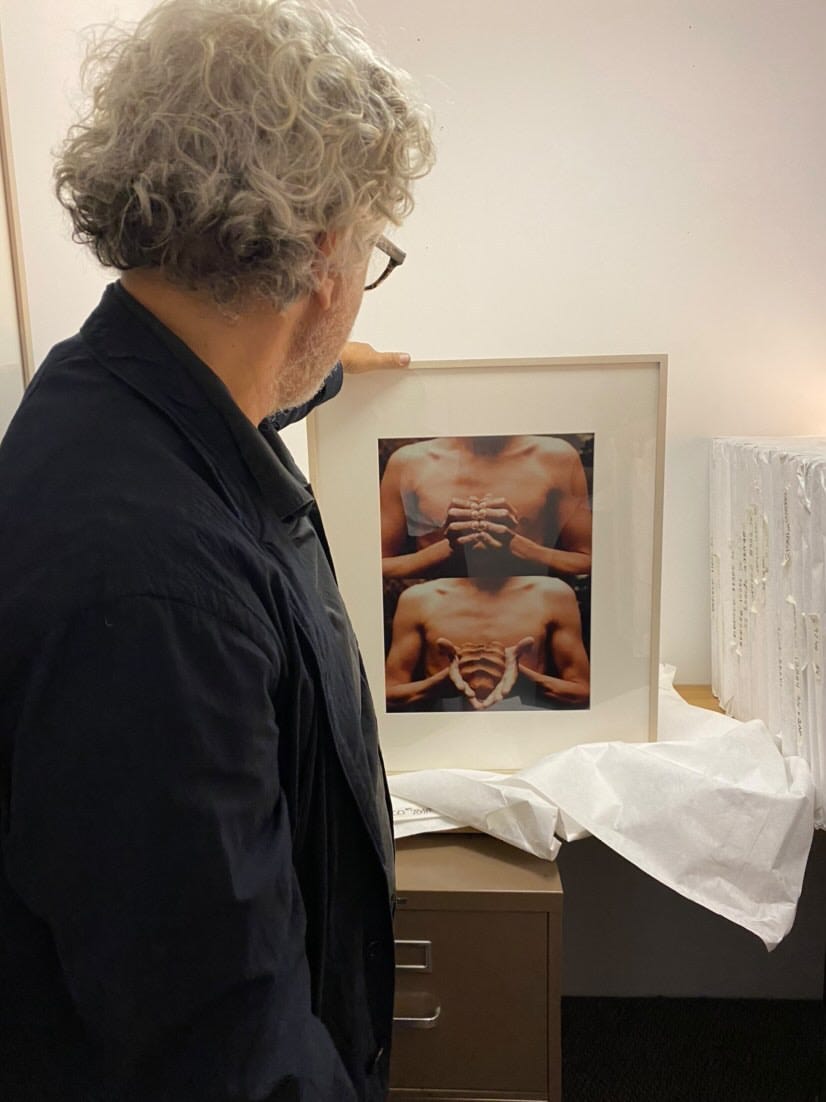

Orozco installing Spacetime

An inescapable certainty of life in the art world, aside from death and taxes, is the need for promotion. This inescapable activity, as many know, is also in crisis as the traditional methods of promotion appear to be on the verge of obsolescence. We are permanently bombarded with advertisements, announcements and invitations to art events, and even in the cases of those events that involve topics and people that we care about, it becomes difficult to prioritize, and as a result we often block much of the invitations that come our way.

Given this environment, it is not surprising that some recur to the tried-and-true method of word-of-mouth communication to attract guests to their events. As we all know, we might ignore an exhibition announcement, but if the artist or organizer is someone you know and writes you to personally invite you, you will feel much greater pressure and perhaps willingness to oblige.

Word-of-mouth is a key component of the psychological dynamics of the influencer/influenced, but in art it operates in more nuanced and complex ways. We might associate word-of-mouth communication as a marketing strategy in a market-centered art world, but the fact is that word-of-mouth has long been more of a vital strategy of communication in social contexts where communication is surveilled and policed.

This practice is key for the art community in places like Cuba. The Cuban curator Elvia Rosa Castro, now based in North Carolina, described to me how “word-of-mouth” in the Cuban art world is literally the main way by which the art community connects, which is possible given the close proximity that the community shares professionally. “First you have the art academy and the provincial art schools that bring the art students and professors together— they are all in direct contact eight days a week. Openings are massive and a gathering point for artists, critics and curators who spend their times gossiping there and also in bars. We have phone land lines, but there you need to speak in code since the majority of phones are tapped, and then WhatsApp and Telegram which are important in Cuba as they are less susceptible for hacking by state security.”

It is well-known that during the communist era in Eastern Bloc, particularly in the 60s, 70s and 80s, groups of artists in countries like the Soviet Union, Romania and Hungary would gather in private organizing exhibitions in apartments and publishing underground journals, using word-of-mouth to organize and communicate, mainly because any other means of communication (phone, mail, etc.) would be subject to surveillance by the state. As curator Janka Vukmir, director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and someone very familiar with this period told me, “there were little substitutes” for word-of mouth-communications, and given that state censorship operated in multiple ways it was paramount to create alternative channels of communication: “The conventional invitations were a tool of official institutions, and the rest of information was disseminated mostly by word-of-mouth. Invitations to unofficial events were mostly made and multiplied by hand.”

In Hungary in 1966, artists Tamás Szentjóby and Gábor Altorjay organized “Lunch, the First Happening in Hungary” in a private cellar— an event that was reported on by the secret police (thankfully, this type of surveillance in retrospect became an efficient form of art historical documentation). One of the several prominent artists that emerged from this underground art community was Dóra Maurer, who produced experimental work outside of the accepted parameters of the Hungarian system.

Dora Máurer, Seven Twists, 1979

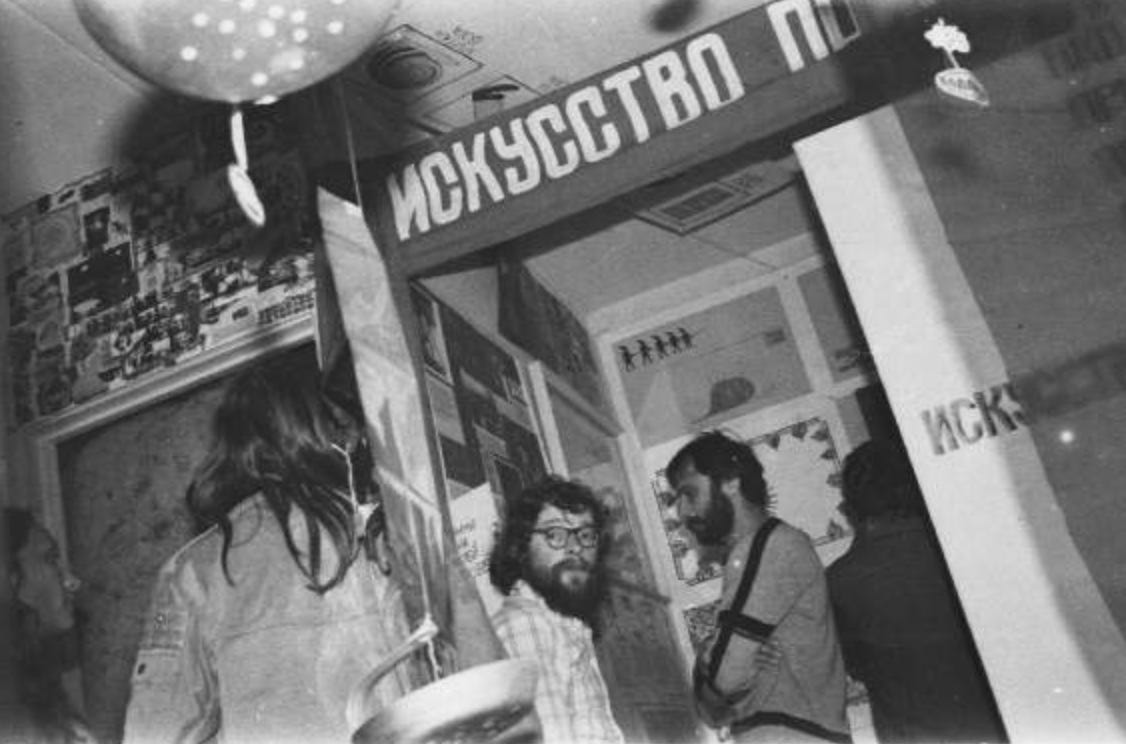

Another important example in this category of word-of-mouth artist communities was the collective APTArt, a group of artists who organized exhibitions in their private apartments in Moscow between 1982 and 1984. One of the artists from this group, Vadim Zakharov, still produces exhibitions in his own apartment in Berlin.

APTArt exhibition, Moscow, 1982

The connection between word-of-mouth, conceptual art in Eastern Europe and private apartments inevitably led me to remember the intentionally clandestine Salon de Fleurus in New York City, which was open from 1992 to 2014. I learned about it via word-of-mouth from Slovenian artists Marjetica Potrc and Miran Mohar and eventually made it to the space one night led by Mohar, who told me one day: “I can’t tell you anything about it. Just meet me in the corner of Mulberry and Spring at 9pm”. The Salon de Fleurus doubled as an artwork and an “ethnographic installation” (as described once by a visitor) intentionally reminiscent of Gertrude Stein’s parlor at 27 rue de Fleurus from 1904-34 in Paris, arguably the conceptual birthplace of modernism where Picassos, Braques and Cezannes hung together for the first time. At the Salon visitors could see painted copies of the works originally on view in Stein’s apartment, presented not as copies but as anonymous works.

Salon de Fleurus

The Doorman— the Salon’s ever-present and self-efffacing host— shunned any traditional promotion (print or web), relying instead on word-of-mouth. Visiting hours were also unorthodox, it being open only at night.

I asked the Doorman, who hails from Belgrade, whether the story of exhibitions in apartments in Eastern Europe had played a role in Salon— with the full understanding that censorship did not take the same form in Yugoslavia as it did in other Eastern bloc countries. (Vukmir: “Yugoslavia officially did not have censorship, not mentioned in [the] Constitution(s). Yet the mechanism was there, organized through diverse bodies, committees etc.”)

The Doorman told me he was involved from 1972 to 1980 with Students Cultural Center in Belgrade. “However, because of personal disagreements in 1980 I staged an exhibition in my apartment. This definitely played a role in appearance of the Salon in NY.”

The private experience (i.e. not being in a public space) was interestingly complemented by the fact that visitors were presented with a space that was declared anonymous, as according to the Doorman’s explanation, “the anonymity came as a result of my understanding of copy [ie. the painting reproductions in the space] not having the notion of author.”

I asked myself about the extent to which private communication becomes exclusivist. I posed the question to Gabriel Orozco in terms of his project. He turned the problem back to me, pointing out that Dada artists (like the ones whose work used to be featured in that space when it was a gallery) would make exhibitions for each other. “Sometimes I feel that publicity is a false democracy. Making noise doesn’t necessarily work better.”

I go back to the role that word-of-mouth played in the life of Salon de Fleurus while it existed in that small back apartment on Mulberry and Spring (when it came the time to close, in 2014 due to an unreasonable landlord, a very small group of in-the-know curators and friends gathered there with the Doorman to say goodbye— a word-of-mouth gathering of course). The fact that Salon played hard to get, and that it would be hard to find, was one of the things that made this kind of post-modern speakeasy stand above almost any other art experience one could have in New York— kind of like the prize of a scavenger hunt. All of which makes me think that, in the end, all these projects both recognize and highlight one of the great contradictions of contemporary exhibition-making: art needs to be highly public, but at the same time it is measured inasmuch as it becomes a highly personal (or personalized) experience offering us unique insights. It needs to be visible to all, but it also needs to feel like secret knowledge, like a great revelation whispered to your ear that opens your eyes.