The Guinness World Record for viewing public screenings of the same film is held by Ramiro Alanis of Florida, who watched Spider-Man: No Way Home 292 times between December 16, 2021, and March 15, 2022. Alanis watched 972 hours of film, or the equivalent of 30 days of nonstop screening— arguably having memorized the entire film and being able to recite the dialogue out loud (for the viewing to count as uninterrupted, he was not allowed to even go to the bathroom, which invalidated about 11 viewings).

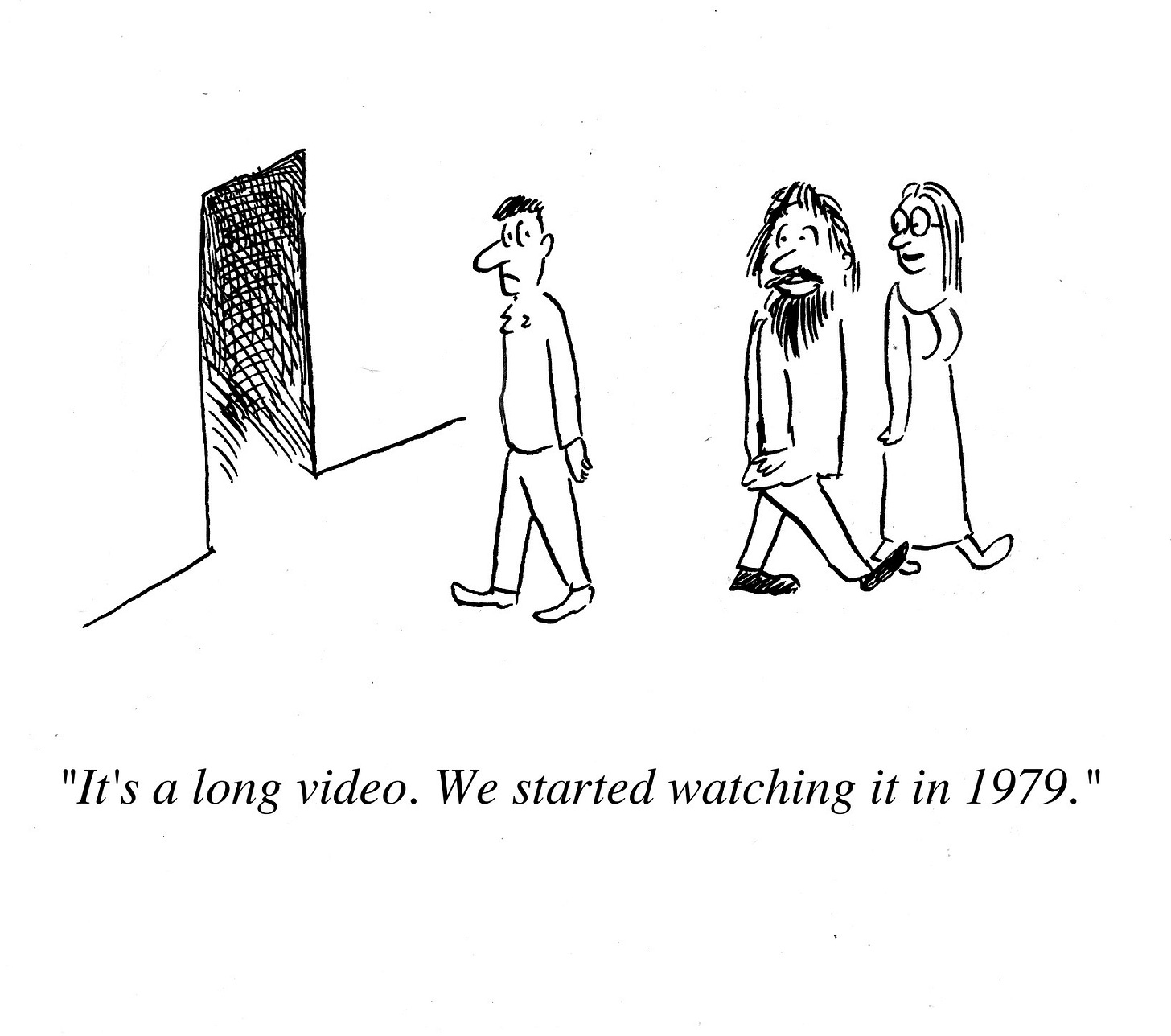

I doubt many of us share Alanis’s competitive obsessiveness. However, I also don’t think that “repetitive spectatorship” is such an unusual phenomenon: I have been doing quite a bit of that myself in recent weeks.

The current political moment, with the onslaught of disturbing policies and dismantling of the world as we know it in multiple fronts, by design is putting us in information overload and pushing us to disengage instead of fighting back. As a result, we tend to retrench toward what we know and enjoy— that which is familiar and reassuring. A friend of mine once told me that whenever she felt upset or out of sorts her go-to antidote was reading Hannah Arendt. “You can always find something that can help you gain some clarity”, she told me.

This phenomenon is known as cognitive familiarity: during stressful times we gravitate toward things that we are familiar with (kind of like intellectual comfort food), and our brain is reassured by patterns that we already know.

One can critique this attitude by dismissing it as escapism, or unwillingness to deal with reality. But it is more complicated than that. This connects with the old value contrast between breadth and depth in learning (which I have previously written about using the analogy of the Fox and the Hedgehog). Do we learn more from the deep exploration of one subject or from the exploration of many subjects? Borges was a big proponent of the former. While his writings, interviews and lectures reveal an encyclopedic knowledge (and he had seemingly read more books than most of us will ever read in our lifetime), he in fact was more of a deep re-reader of about two dozen authors, like Shakespeare and Milton, Stevenson, de Quincey, Spinoza, Cervantes and others. In an art world that is constantly overwhelming us with new art and artists it is helpful to have a firm handle of a limited set of references from where we can speak in a more informed way.

The reduced repertoire of references and repeated viewership or spectatorship also bring benefits. I think of my mother’s family, my aunts and uncles, all of which were huge opera aficionados and who had opera was playing all day in their homes. As we know, operas like plays are set stories, and one does not watch or listen to them to be surprised by their literary value or dramatic twists, which in general are not very good or interesting; most operas have rather incongruous or problematic plots (like, for example, why in hell would Calaf be so smitten with Turandot, who sadistically murders her earnest suitors by demanding them to solve a riddle, while the innocent and selfless slave Liù commits suicide for her unconditional love of her master Calaf and he doesn’t seem to care?). The focus to the aficionado is, instead of the plot, the interpretation of each aria, duets and other sections. For the opera aficionado, the pleasure derives in being able to compare and contrast one version with another, and become an expert in determining musical interpretive qualities between versions. Perhaps these kind of considerations were in the mind of the Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, who in 2011 for a Performa commission he presented the last ensemble scene of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro for 12 consecutive hours (typically this section lasts around 3 minutes). A friend who attended the performance was completely exhilarated, specially toward the cathartic end. Clearly the Rococo-era opera turned endurance performance had also transformed, by mere repetition, into something completely different, and also transformed the public.

During the pandemic, in 2020, a moment that was very dark for all of us in so many respects, I found myself late at night revisiting the old lectures of my old art history professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Bob Loescher, who I have mentioned many times in this column— a knowledgeable educator who had a great impact in my student years, someone whose lectures students would flock on to listen, because they all were close to theatrical experiences. I happened to find a couple scattered online amateur videos taken in sometime in the late 90s or early 2000s, of him lecturing. Although I knew the subject matter well, and in fact recognized that some of the views and perspectives in those lectures are a bit dated (most of these videos are more than a quarter-century old, after all), I loved listening to them many times over, paying attention to his turns of phrase, his way of creating grand summaries, and even inserting the occassional off-color joke here and there. Doing so became a soothing process for me. Why was that so?

I surmise it is precisely because of cognitive familiarity. The need for intellectual comfort food stems, I believe, from a feeling of uncertainty about the world and the challenging reality around us, so much so that we seek to grab on to something that we find affirming. Practically memorizing those lectures allowed me to reflect on each of the issues discussed and reflect on each phrase on my own. But at some point this repetitive viewing also becomes a ritualistic experience, a state of mind perhaps not dissimilar to a form of meditation.

Perhaps the reason that the idea that one should watch a movie, listen to a song, or re-read a short story hundreds of times feels strange is because of the temporal accommodations one needs to make to make it happen. Certainly, we can have that experience when we own a painting, and engage with endless contemplation of it. But even there, we want and in fact enjoy a sequential experience— I will explain. When I worked at MoMA’s Education Department we found something interesting regarding the use of our audio guide. The museum has a series of verbal descriptions of works specifically created for the visually impaired— carefully constructed, detailed accounting of individual works without any editorial or art historical commentary. What we learned was that the descriptions were being used by many, likely thousands of people— which indicated that those using the descriptions were not necessarily visually impaired, but also likely people who simply wanted to use the audio to help them reaffirm what they were already seeing. It was, I suspect, a version of cognitive familiarity, but one where one reviews the basics to fully establish the image in one’s mind, and perhaps based on those basics, develop one’s own thoughts and relationship with the work.

It is a form of passive contemplation that is in fact active. It is perhaps a way to integrate art into the every day, and by making it so familiar, use it to give us grounding amidst the uncertainties of our daily living.