In 1964, Umberto Eco published Apocalittici e Integrati, an essay exploring the emerging positions around mass media in the mid-20th century. Rather than advocating for a particular stance, Eco aimed to create a critical map of the debate. On one side were the Marxist-influenced critics of mass culture—think Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse of the Frankfurt School—whom Eco labeled the "Apocalyptics." On the other were those more optimistic about the cultural contributions of mass media, valuing its challenge to elitism and pessimism—the "Integrated." Eco, with certain caveats, placed himself somewhat in the latter camp.

If we extend this taxonomy to the art produced during that period—keeping in mind the limitations of any categorical system—it would be tempting to describe Pop Art as “integrated,” and minimalism, conceptual art, feminism, and institutional critique as “apocalyptic.” I find Eco’s framework—taxonomies being a personal fondness—still valuable, even when applied beyond the mass media discourse to consider how contemporary art engages with political and social issues more broadly.

Eco’s dichotomy came to mind recently as I walked through a large kunsthalle (which shall remain unnamed). One after another, I encountered artworks by contemporary artists that offered grim indictments of the illiberal, authoritarian world we seem to be descending into: the dismantling of transgender rights, the criminalization of immigration, environmental racism, white supremacy, the triumph of oligarchy, patriarchy, and sexual oppression, police violence, and the carceral state.

Having been a museum animal for many decades, I know that all of these topics are not uncommon to the repertoire of cultural critique; they belong, naturally, to the territory of contemporary art practice and institutional display. For those of us embedded in this world, we understand that zeitgeists are not contrived—they emerge in response to historical pressures. And this moment is among the darkest.

Yet I couldn’t shake the feeling that this spirit of critique—of protest and lament manifested through videos, monumental paintings, solemn sound installations, and memorial sculptures—has, in a strange way, become its own form of academia. Tragedy, commodified. Protest, aestheticized. The very dynamics Eco hinted at, but somehow compressed into one: an “apocalyptic integration”.

Eco’s distinctions help us see not only how critique survives in commodified form, but how it shifts meaning in transit—from urgency to academic exercise, from resistance to recognizable content. Contemporary art, in this light, may be the most integrated apocalyptic gesture we have.

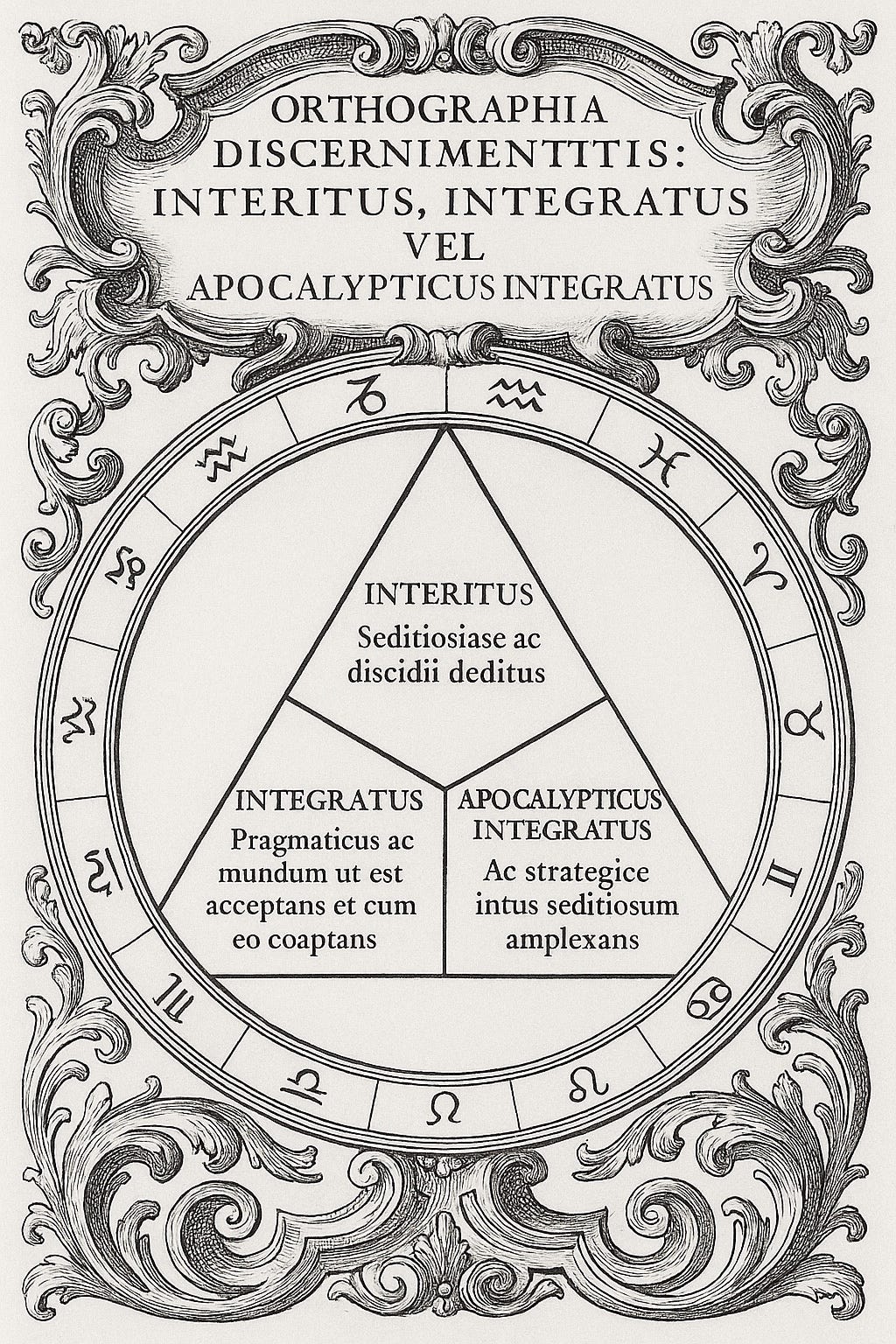

For days, I debated how best to explore this topic. I have a deep allergy to traditional art criticism and resist the stance of moral or aesthetic authority. I thought, instead, to offer—echoing Eco’s own epistemological approach— a modest mapping of the political contours of contemporary artistic practice, the very field within which I am implicated. The questions I asked myself were many: am I apocalyptic when I become a truth-teller? Has critique become a style? Does my protest coexist too comfortably with spectacle? Am I a fashion victim of biennial language? Should I reject the embrace of the very institutions I claim to critique? Am I just another cog in the machinery of protest economics? Will my dissent end up as decor in a place like Mar-a-Lago? Am I Apocalyptic, Integrated, or both?

To consider these questions I thought I would try a different approach: a playful but sincere personality test. The question of whether we are Apocalyptic, Integrated, or Apocalyptically Integrated is one we should each explore ourselves.

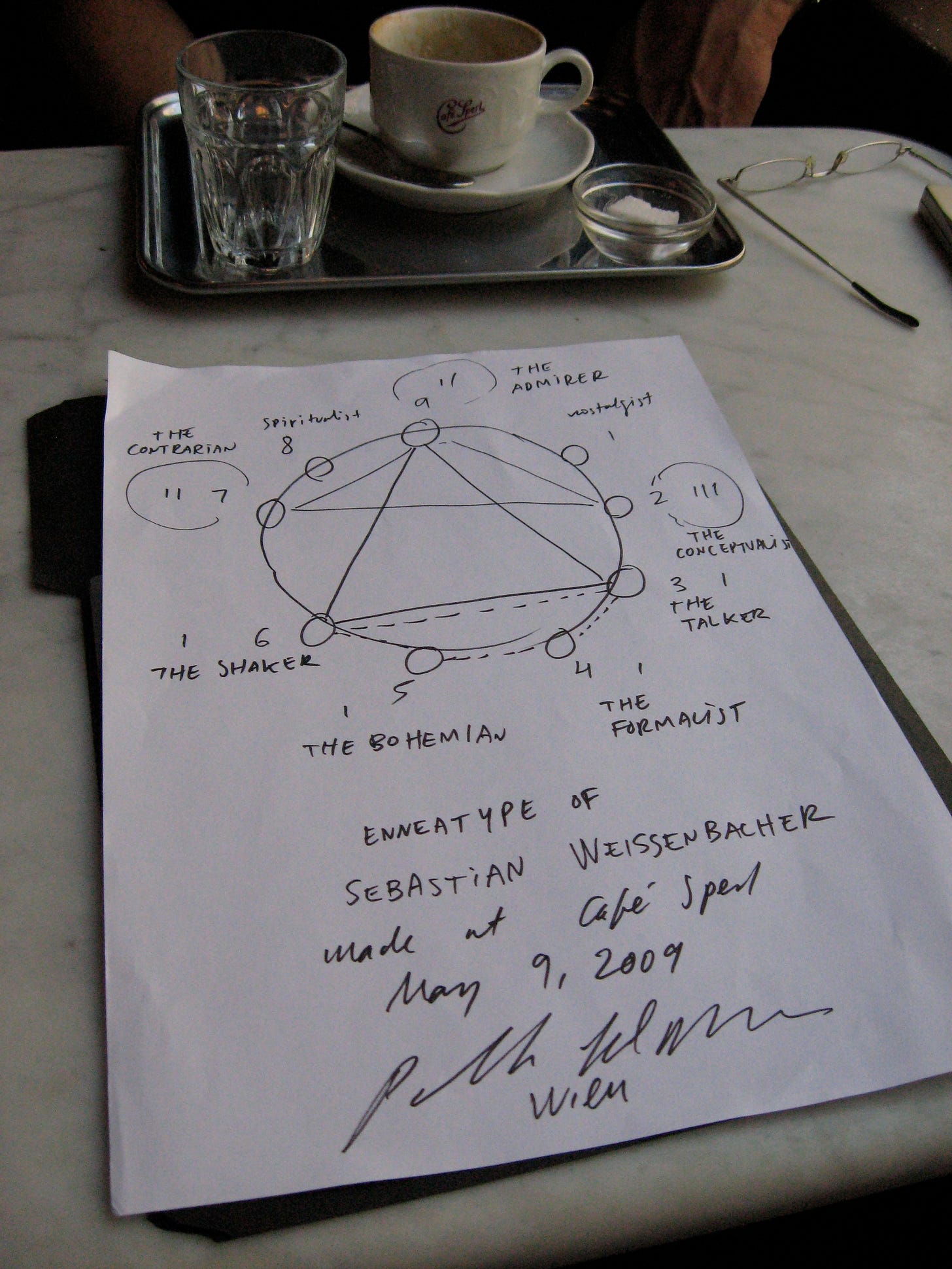

In 2009, I was invited to Vienna by curators Elsie Lahner and Jasper Sharp, who were editing an issue of Parabol (an important Austrian art magazine) on the subject of value. I proposed to create an art personality test inspired by the Enneagram, a model developed by Bolivian philosopher Oscar Ichazo. Over several days in a Viennese café, I met with a number of willing participants and constructed personalized enneagrams based on a series of questions.

In that same spirit—and with similar unscientific speculation—I offer the following personality test. Take it yourself, or share it with friends, colleagues, or loved ones, to explore what form of artistic sensibility predominates in you:

1. Apocalyptic – Committed to protest and disruption

2. Integrated – Pragmatic, accepting of the world as it is and willing to engage with it

3. Apocalyptically Integrated – Strategically embracing protest from within

Art Personality Survey: Apocalyptic, Integrated, or Apocalyptically Integrated?

Instructions: For each question, choose the answer that feels most true to you. Keep track of your letter choices.

1. You walk into a museum and see a sleek video installation about climate change sponsored by an oil company. You...

· A. Scream internally and wonder when protest lost its teeth.

· B. Think: at least people are talking about it.

· C. Admire how protest can be packaged so convincingly.

2. You hear that a major biennial is themed “Decolonizing the Sensorium.” You...

· A. Roll your eyes and question who is actually being decolonized.

· B. Feel curious and look forward to the programming.

· C. Already drafted a proposal about decolonial soundscapes last year.

3. Your friend posts a story on Instagram critiquing capitalism using emojis and Canva graphics. You...

· A. Despair that protest has become a branding strategy.

· B. Like and share—it’s a start.

· C. Save the post as reference for your own upcoming work.

4. When thinking about the purpose of art, you lean toward...

· A. Uncompromising confrontation with oppressive systems.

· B. Creating space for dialogue, even within existing institutions.

· C. Revealing complicity through immersive, beautifully funded critique.

5. Your bookshelf features...

· A. Marx, Debord, and Audre Lorde, heavily underlined.

· B. Claire Bishop, Grant Kester, and museum catalogs.

· C. A mix of critical theory and Venice Biennale guides (with sticky notes).

6. A collector wants to buy your deeply political work. You...

· A. Decline and suggest they donate to a mutual aid fund.

· B. Accept—it helps you keep making art.

· C. Negotiate a clause to fund a public program that mirrors the work’s critique.

7. A reviewer calls your work “hauntingly relevant.” You...

· A. Worry that you’ve become predictable.

· B. Feel validated—it’s hard to reach people.

· C. Wonder if you should shift your tone for the next grant cycle.

8. Your ideal audience is...

· A. People outside the art world who experience the injustices your work addresses.

· B. A broad public, including institutions.

· C. The art world—because that’s where dissent can most theatrically perform itself.

9. You think the biggest risk in art today is...

· A. Being neutral in the face of injustice.

· B. Becoming inaccessible to wider audiences.

· C. Letting critique become a style guide.

10. At night, you secretly worry that...

· A. No one is listening.

· B. Change is too slow.

· C. You’re part of the very system you want to dismantle.

Scoring Key

For each A, give yourself 3 points

For each B, 2 points

For each C, 1 point

Results

25–30 points: The Apocalyptic

You believe art must disturb, disrupt, and dissent—even if that means standing at the margins. You distrust institutions and view commodification as a trap. You may not sleep well at night, but your rage keeps you honest. Beware of hypertension and ulcers.

17–24 points: The Apocalyptically Integrated

You exist in contradiction—and you know it. You embrace the aesthetics of protest while benefiting from its visibility. You navigate institutions carefully, creating work that critiques the system from within, though you sometimes wonder if you're just decorating the apocalypse.

10–16 points: The Integrated

You believe in dialogue, access, and the transformative power of culture—even commodified culture. You think change is possible from within, and that beauty and critique can coexist. You’re not naïve, just pragmatic; but you might be accused of being Machiavellian.