Intellectual Escape

Creative procrastination and the importance of pet projects.

One my favorite films of all time is Barton Fink — the 1991 dark comedy and psychological thriller by the Coen brothers . The movie tells the story of a celebrated New York playwright in the 1940s who is brought to Hollywood to write the screenplay of a B-level wrestling film and, suffering from writer’s block in a strange and musty hotel, is then enveloped in a web of unfortunate events. Barton Fink was a critical success (if not a commercial one when released) and won the Palme D’Or at Cannes and three nominations in the Academy Awards. I consider it the Coen brother’s best film, as well as one of the most powerful and complex mainstream post-modern artworks of the end of the 20th century. In its dreamlike elements it also strikes me as a film that more closely resembles aspects of Latin American literature of the 1960s without it being at all about Latin America: there are narrative aspects of the story that resonate with the strategies and sensibilities of García Márquez, Borges, Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, and even Salvador Elizondo. The other day when I watched the film again and contemplated the eerie and mysterious atmosphere of the hotel Earle where Fink checks in, I recalled of all things the dark house in downtown Mexico City where Felipe Montero is led to work on a project, hired by an elderly woman—the setting for Fuentes’ novella Aura.

The other interesting background detail about the making of the film, which I often think about and which incidentally is also somehow related to the actual plot, is that the Coen brothers wrote it while they were themselves experiencing writer’s block while writing Miller’s Crossing.

The film is thus not just a work about the creative process, but the very back story of its making points at a phenomenon that I have often been interested in: the inspirational and liberating power of the pet project.

The theory about the creative value of the side (or pet) project goes something like this: the life of professional artist is usually scheduled around deadlines and timetables that pertain to commissioned projects (be it films, books, exhibitions, etc). Often these projects become challenging and the work in making them can be tedious, stressful or boring. Especially when they are large, and the stakes are high, the artist can feel paralyzed at times, uncertain how to take each step. This is where the pet project comes in, offering the exact opposite: a low-stakes, intellectually stimulating problem, where there is no harm in trying to solve it. And that, in contrast, triggers joy and creativity.

For a long time corporate psychologists have argued that allowing employees to pursue creative hobbies improves their performance. This is the reason why Google created its famous “20% rule” where employees are encouraged to devote 20% of the time in projects they are passionate about (although they still request that the projects advance Google’s mission, which might limit the degree of passion one might undertake). Examples like these might support the general principle that when a professional artist undertakes a pet creative project, using their full expertise and training and intellect, but with the enthusiasm of a hobbyist, the result can be highly rewarding.

To review such a creative scenario: we have, on the one hand, what I will call the “main art project”— a project that an artist is expected to develop and deliver; it is the result of a formal commitment that might involve public visibility, money, and a concrete deliverable (often with a deadline). Depending on the size of the project the stakes can be high and the risk of a negative critical reception can be highly damaging. The creative process under this conditions often feels more like regular work, to the point that one might wonder if one is making any art at all.

In those circumstances, artists sometimes turn to an escape valve. They might turn to another project for the purposes of distraction and self-entertainment. The stakes are low; one is primarily playing. And because there is no harm in failing, the freedom one feels is great. One levitates while making a pet (or side) project.

But there is an important detail to keep in mind. The side project cannot exist without the dominance and demands imposed by a central project. It draws its energy from being the counterpoint to the project that is being made by obligation, that presents large production problems, that feels intractable, that at a certain point does not feel creative anymore.

In this sense, side project-making is a form of what some have termed “creative procrastination”— namely, the phenomenon of putting off large projects by doing more immediate projects that feel more stimulating and interesting. The advantage of working this way is that there are no high expectations from what might come out of the side project; there might not be financial incentives either; mostly it is a purely creative endeavor where experimentation dominates.

Side projects can be merely creative distractions, but it is important to pay attention to where they take us, as they can often unlock new ideas or unanticipated directions, then leading to the side project to become a main project (as was the case of Barton Fink).

I believe I experienced a small and humble version of this phenomenon in the early summer of 2020— the height of the pandemic period, with everyone confined to their homes and to Zoom, amidst an economic shutdown, the national reckoning about race after the killing of George Floyd in the US, and the intensifying political polarization in the country. Having to work like so many via Zoom and attending back to back meetings sometimes for 8 hours straight, I started secretly doodling during the periods where I was listening to presentations (doodling, to clarify, is not a sign of disrespect: studies in fact show that doodling aids in learning and allows to increase concentration). Furthermore, it has also been argued that doodling can help reveal our subconscious thinking. This is yet another gift of the side project: the central project requires our conscious attention, and intentionality in making, even by the professional, can curtail some of our most creative sides. The unbridled, experimental nature of the side project in contrast can uncover aspects of ourselves that we were not aware about.

My pandemic doodles, made amidst the stupor of those never-ending Zoom meetings, were decidedly dark and sinister, and brought me back to the times when I was a child. One of my earliest childhood memories, as a 4-year-old, was going to my father’s office in the lower level of our house, where he had a small library and ask him to show me “el libro de las cabezas” (“the book of the heads”). He would then smile, stand up from his desk and pull out a giant leather volume to show me.

The “book of the heads” was no other than an edition of Francois Michaud's History of the Crusades from 1877, with engravings by the great French artist Gustav Doré. The book included bleak images such as the depiction of how during the siege of the Turkish city of Nicaea in 1097 Crusaders threw the heads of those they slaughtered over the walls of the city. ( It might now appear like a really inappropriate thing to show to a 4-year-old, but I cherish that very first experience in my life looking and discussing artworks, always under the loving care and storytelling of my dad). Doré’s illustrations were always important to me and partially because of them, as an art student in Chicago I gravitated toward etching and intaglio.

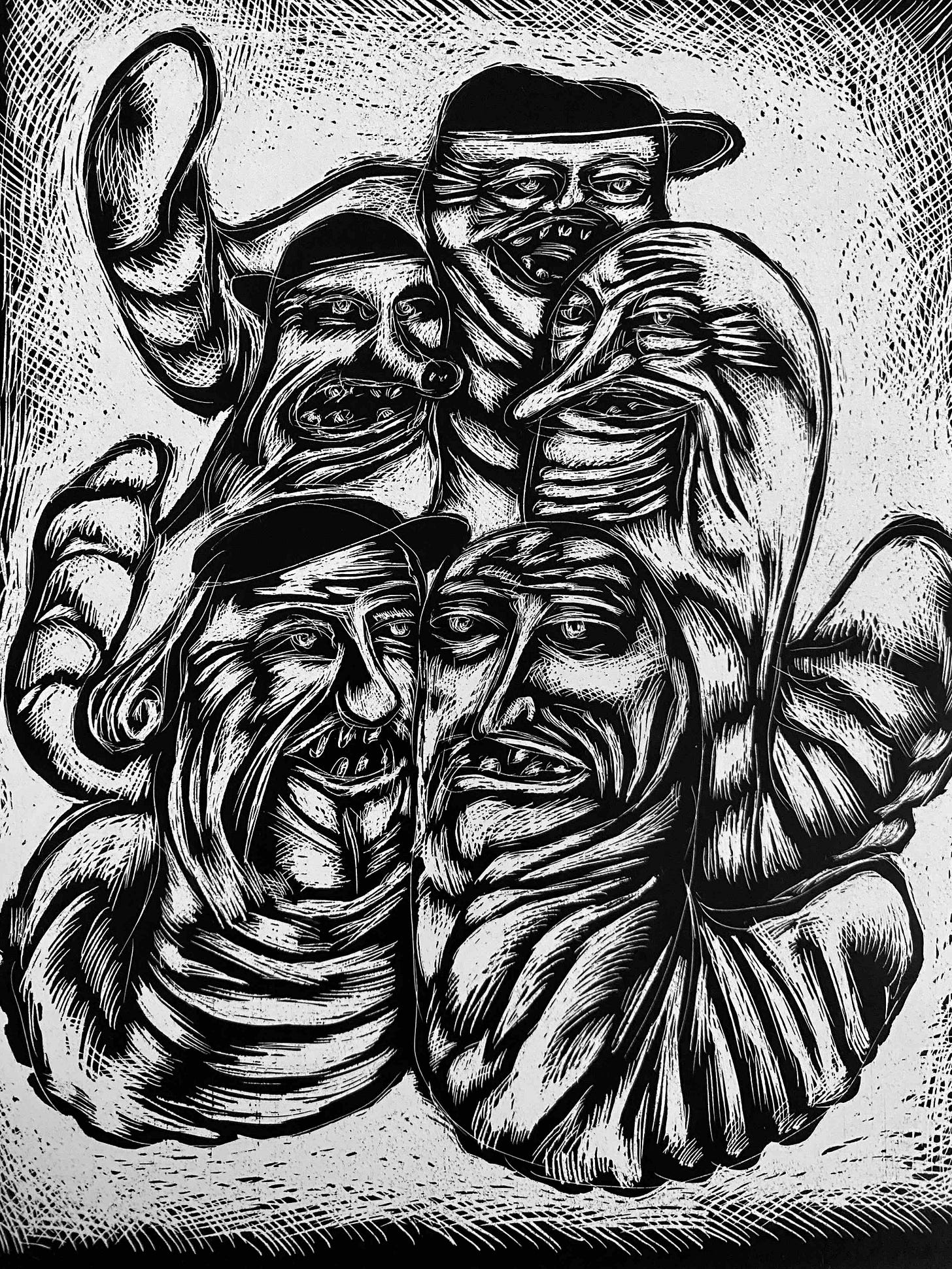

I later transferred the images of my Zoom doodles (originally made in pen on paper) onto scratchboard, working from dark to light and somehow invoking the etching technique. The series, exhibited last year and titled Penumbra, were decidedly a small side project, but in my view one that depicts the emotional state that I was experiencing during those nightmarish months.

Penumbra #17: Quodlibet. 2020, 8x10"

Penumbra #5: School Play. 2020, 8x10"

There is much more to say about the subject of side projects, but I can’t address them all here. Suffice to make one question and one observation. First, the question: if inspiring side projects emerge from having to do uninspiring main projects, can that dynamic be artificially induced? The idea might be a form of wishful thinking, as creating artificial pressure (e.g. a fake “main project” to work on) can hardly create the sort of pressure that would compel us to genuinely pursue a side project as distraction. But maybe the scheme could be pulled off using a form of reverse psychology.

Second, the observation: the dynamic tension between the central and the side project is not only true in the creative process, but it can also exist within a work. The side project inside the central work is closer to a coda, a footnote, that at times might feel unimportant but that becomes paramount.

In Barton Fink, the title character, wrestling with his inability to write a wrestling film, desperately faces the blank page on his typewriter in his hot and humid hotel room, where, on the wall hangs a decorative reproduction of a painting showing a woman on the beach, peacefully facing toward the sea horizon. Her untroubled and relaxing pose in that idyllic landscape contrasts with the mental and emotional struggle that Fink is undergoing.

At the very end of the film, after all the whirlwind of experiences that have landed Fink in a hellish and seemingly inescapable trap, he wanders onto a beach and plops himself in the sand, listless and defeated. Then a woman identical to the illustration in his hotel room greets him and sits in front of him, exactly recreating the image of the reproduction. The film then ends with that one side image; one that speaks of the relationship between the fiction writer and their real life, about escapism and hard facts, a spontaneous performative doodle of the subconscious mind that indirectly helps bring everything else into focus.

Fans of Coen brothers’ movies love to endlessly interpret the meaning of every element in their films, constructing complex mythologies and hermetic meanings. Ethan Coen said in an interview that the image in the painting was meant to give “the feeling of consolation”.

To me, perhaps in addition, it represents the glamorous lure of the side project.