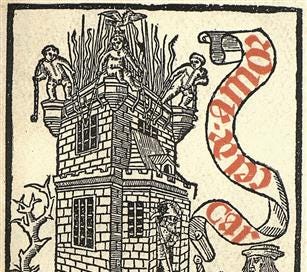

Cárcel de Amor, Illustration by Johan Rosenbach, 1493

Those who set their eyes on the sun, the longer they stare at it the more they are blinded, just as I, when I contemplate your beauty, the more blind my senses become.”

Diego De San Pedro, Cárcel de Amor

To understand is to forget about loving.

Fernando Pessoa

A decade or so ago I worked on a video project about an authoritarian cult in the United States. It was the story of an intentional community created by self-taught psychotherapists in the late 1950s and lasting until the early 90s. This group was unique in its radical Marxists ideas and its particular affinity and investment in art making and the leftist, political nature of its collective work (I will refrain from mentioning the name of the cult given that many of its ex-followers are still alive today). Those who joined the community were made to cut ties with their families and develop an aversion against the conventions around the nuclear family. They were forbidden to have monogamic relationships and all were encouraged to have sex with one another. The economy of the group was centralized and managed by leadership even as members maintained regular jobs in the outside world.

The group collapsed after at least one child custody battle and denunciations by disaffected members made the cult public, making details about it hit the tabloids, all of which coincided with the death of the charismatic cult leader.

I had found the history of this cult particularly interesting given its secular nature, the way it espoused radical leftist ideas and the fact that they regarded collective art making as an important avenue to present their ideas publicly.

My video about this story, developed mainly based in press and other documentary materials, was part of a small group exhibition in a gallery in New York. A few weeks into the exhibition, I was told by the gallery that the son of the cult leader had visited the exhibition an wanted to meet with me.

I was surprised, excited and frankly nervous, but I reached out to him. We agreed to meet for coffee.

He was in his late 20s — he was the youngest of his father’s children, who had many partners throughout his life. The encounter overall was very odd. My recollection of him were his unusual social interaction traits — little to no eye contact, awkward facial expressions and movements that were hard to read, and abrupt or unexpected reactions during the conversation. We spoke about the context where he grew up. It appeared nearly impossible for him to characterize how he felt about it: he would oscillate between acknowledging abuse and pointing out good aspects about being in that community. The word “cult” never came up in the conversation.

I wanted to learn more about him, but primarily I wanted to understand why he wanted to meet with me.

I did not get much clarity from our encounter. He appeared to be simultaneously excited and disturbed by the fact that I had been interested in the story of his community. He told me that he was an artist, and that he also had ideas about doing an art project about it. At times he appeared to show anger, saying that the story was his, not mine, and that he saw my research as an intrusion, if not an unethical appropriation. But his long-winded, thinking- out loud stream of consciousness at times felt contradictory, and later he appeared to want to instead share his enthusiasm for his story. If I recall correctly, he said he would send me thoughts about a work in progress of his (a film?) about this experience.

We lost touch shortly afterward, and I did not continue pursuing my communication with him.

My recollection of him is of a person deeply shaken by a deep emotional experience, one that had been so traumatic that to an extent he could still not gain clarity from it. But overall,

my feeling was one of enormous sadness: the image of a person who had undergone a kind of trauma that had made him unable to engage with reality.

In other conversations I managed to have, or comments I heard from, other members of the cult, the common denominator was the very challenge to gain critical distance from how their lives were dominated within the community, and the occasional comment along the lines that “it wasn’t that bad”, and even cherishing aspects about the community they had left behind.

I am no expert in cults. I only know, like most of us who have read about them, about the psychological abuse and intense indoctrination that goes on in authoritarian societies. Those who are recruited are often vulnerable individuals who hold a deep sense of shame about themselves and experience feelings of worthlessness. The cult leader, almost always a charismatic individual, gives them a sense of purpose and emotional support in a community.

The abusive relationship depends on making any criticism by any of the subjects to the leader a complete betrayal; fear becomes the common denominator throughout the process. But the moment in which the subject arrives to the point of total submission is one that is best understood as one marked by emotional attachment. This is why, in 1984, George Orwell makes the Ministry of Love as the most powerful component of Oceania’s government: it is the ministry dedicated to breaking individuals into complete submission after a brutal brainwashing, ending like the main character, Winston, who at the end has nothing but pure love for Big Brother.

Of all the phrases wielded during the last 5 years of protests and political sloganeering, the one that has always seemed most cloying to me is “Love Trumps Hate”, in spite of it being ultimately true and in spite of the precious principle of using non-violence and empathy as a tool to stop hatred, to which I always subscribed. But the phrase, upon later reflection, made me think that it does reveal the crucial core lies at the center of the Trumpist cult: it is not the violence, racism and unhinged violence against others, but rather the absolute, abandoned devotion to the leader. Violence only as a savage, desperate, and defensive act that results from wanting to protect a pure idea of oneself and their unique relationship to their leader. When Trump said, last week during the Capitol riots, “We love you. You are very special”, he was underlining that special relationship that cult leaders typically have with their followers. In the Trump universe, like Winston at the end of Orwell’s novel, or like in most religions, spiritual rapture consists in the feeling that you have a personal relationship with God, the fact that God loves you and understands you, that you embody God. For many men who feel emasculated in American society, those feeling left behind and frustrated with their lives, the fact that their president understood them meant everything. This is why, it seems to me, they can honestly argue that their movement is not about racism, xenophobia or bigotry, but in building a world in which, in their imagination, their relationship flourishes unimpeded by the constraints of what many of us, “the others”, understand to be the basis of democracy and tolerance.

But once the ploy succeeds, as we know, the process of getting out of it is even more treacherous than when one is prey to sentimental seduction. My experience talking to the son of the cult leader made me think that the damage was so deep, the hurt so embodied, that emerging from it looked impossible. After all that abuse, it seemed hard to imagine that this man would be able to see the world in an objective way and overcome his own self-doubt to ever reach firm beliefs about anything that would help him move forward in life.

This is the disquieting question that we face now, after emerging from this traumatic period in history: whether we will be able to repair the damage done by this deception. Ovid himself, in The Art of Love, warns of the methods of the professional seducer:

Some men conduct their siege under a disguise

Of passion in order to lay hands on the prize—

A shameful ploy. Don’t be fooled by his sleek,

Scented hair, tight-laced shoe-tongues, chic,

Fine-textured togas, or the ring

(Single or plural) glittering

On his hand.

More than two thousand years later, the description feels all to apt, and all too familiar.

I too have been thinking recently about Trump supporters in the context of a cult. A recurring theme that I'm seeing among both friends and family and among writers is the struggle to understand how those closest to them can spew hate rhetoric or conspiracy theories, increasingly seeming detached from reality, especially when the person is educated and otherwise a decent person. However, detachment from their previous life and loved ones is exactly what happens when someone joins a cult. Trump is exploiting their prejudice to instill fear and/or that sense of belonging, but their prejudice is not what defines them; if they were not brainwashed they would likely be kinder and more open-minded individuals.

Coming at it from that perspective, this observation of yours in particular hits the mark: "For many men who feel emasculated in American society, those feeling left behind and frustrated with their lives, the fact that their president understood them meant everything. This is why, it seems to me, they can honestly argue that their movement is not about racism, xenophobia or bigotry."

It doesn't take the racism, xenophobia, or bigotry out of the equation or make what is happening any less dangerous. And as you note, whether we can repair the damage is a question mark. But understanding that prejudice is not the sole driving force, that there is something deeper going on psychologically, and recognizing that this is indeed a cult are important first steps toward healing.