As we reach the 200th dispatch of Beautiful Eccentrics, and in advance of our event celebrating the occasion on May 17th, I share the following text.

—

In the fall of 1989, in my freshman year at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I struggled greatly with the English language. My TOEFL score was only good enough to show college-level proficiency, but I still suffered trying to learn new terms and engage in conversation. One of the most challenging classes I took on that first year was Essay Writing, a class taught by Paul Elitzik.

Elitzik, who just retired from SAIC last year, is a native New Yorker and Harvard graduate with strong leftist views, and in his class back then he took special efforts not only to teach us to write clearly, but to look at writing as a way to consider and address important social and political topics. In retrospect, Elitzik’s class was the only place in my first year in art school where we actually debated important social and political issues instead of learning painting or printing technique. He assigned parts of Chomsky’s “Manufacturing Consent,” a book that had just come out the year prior; we discussed First Amendment issues and the controversy about stepping on top of the American Flag as prompted by a piece by a recent graduate, Dread Scott; we discussed culture war issues and the defunding of the NEA.

I did poorly in my first assignments. Elitzik was a really tough editor and was quick to point out my many weaknesses as a young writer, which included not getting straight to the point and doing too many narrative detours. I did not always receive the criticism very well; not least because my pride was hurt, but also because I felt that he did not appreciate or understand what I was trying to do. I started feeling that he and I understood the term “essay” differently. I was coming from a Latin-American writing tradition where, in my view, the aforementioned narrative meandering (at least I thought) was not a diversion but an essential part of the journey. I told Elitzik that I was coming from a very different cultural and historical literary tradition (or at least that is how I rationalized it). Elitzik was sympathetic to my complaint and strategically asked me to write an essay about that. I did produce an amateur and ridiculous essay titled “On Behalf of the Continuous Dialogue”, where I argued that art making should show greater historical consciousness, which in my teenage mind was lacking in contemporary art. Elitzik was the faculty advisor of F Newspaper, the student newspaper of the school, and suggested that my essay should be published there. I was elated. In spite of how embarrassing the article was, I think Elitzik must have been impressed by my passion, because he later asked me if I would be interested in becoming editor of the student newspaper. While the task was daunting, I had been the editor of my high school newspaper — “Horizontes”— so, why not? I welcomed the opportunity and immediately said yes. And thus started my side career in art journalism.

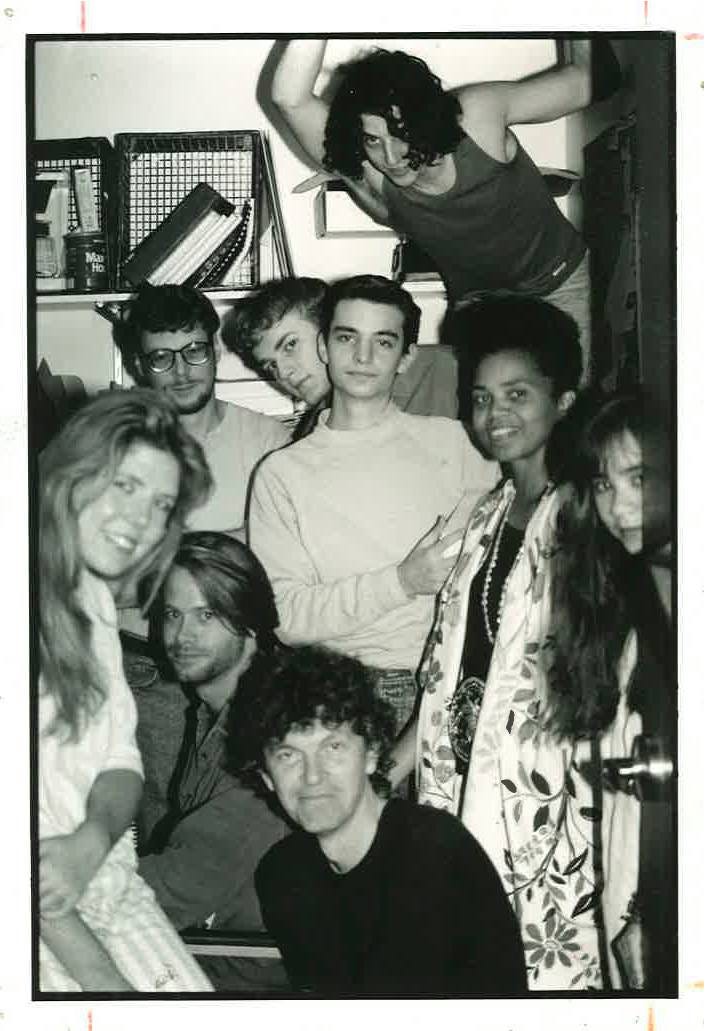

I set up a tiny office in the Wabash Street building of the school, one which was the size of a walk-in closet, and in fact an office that was shared by everyone involved in the paper. During those years we still laid out the paper by hand, using QuarkXPress for typesetting but relying on X-Acto knives to lay out the illustrations and columns. The graphic design advisor was Michael Miner, who had the misfortune of having the same exact first and last name of the art director of the Chicago Reader. We were a motley crew or rebels (and then me, a preppy romantic) writing about things like art and protest, rock bands, and the Chicago Imagists ( who I interviewed at one time). As an interesting aside, my successor as editor a couple years later was no other than Paul Chan— and Paul, like me, kept his interest in publishing, as exemplified by his launching of Badlands Unlimited decades later.

F Newspaper was my first arts management job as well; it included commissioning stories and running meetings to discuss the next issue. I was such a naïve and hapless administrator that I could barely know how to handle basic management issues. During my time, a group of graduate students created an arts supplement for the newspaper titled “Art(I)choke” with photo and writing projects; they mostly did their own thing , and I was too young to know how to supervise them. I imagine most of the older students saw me as an inconsequential figurehead.

However, I did work hard on the paper, and discovered the perks of being the editor of a publication, as small as it was. I was invited to press previews and luncheons at places like the Art Institute of Chicago and the MCA, receiving fancy catalogues of exhibitions and sitting next to actual journalists ( who probably looked down on me with a condescending smirk).

Toward 1994, when I was already working in museums, I met the editors of a new Chicago Tribune free weekly in Spanish, called “¡Exito!” The Tribune Company invested significantly to produce this newspaper, which was meant to engage the growing Latino population in Chicago. One of the editors, Alejandro Escalona, who like me was from Mexico City, approached me to see if I would write for the arts section. I loved being able to write in Spanish again, and in fact the experience allowed me to learn how to write about art in my native language. The ¡Exito! job was easy in some respects: I needed to file a story every week on almost anything that related to the arts: sometimes interviewing an artist, writing about a book, a film, or doing an exhibition review. One time in 1995, when I traveled to Barcelona, I was tasked with writing a story about it and was given a “modem” to file the story. It was the first email I ever sent.

The greatest challenge was in sustaining the weekly rhythm and novelty (some weeks I agonized about what to write about). Although in retrospect, adapting to that weekly rhythm has served me well and at least prepared me for writing this weekly column).

But as in every job, I was sometimes handed down tough tasks. Once I was asked to interview a very commercially successful Mexican painter known for his “accident”-like, vibrant/expressionist paintings— the kind of works that would be at every airport and hotel lobby but that no serious art museum or curator would touch. I had serious doubts about it because I really abhorred the work. When I told an artist friend that I was going to interview him, she started making fun of me, which made my doubts worse. But it was too late to cancel and I had to meet him at the lobby of a fancy hotel. He was delightful, erudite, talking to me about literature and classical music; displaying a wonderful joie de vivre. When I went home I felt incredibly torn. I could not make myself write a negative article about him, nor a positive one either, because it would have been hypocritical. I then told my editor that I simply could not do the job — the only time in my life I have done such a thing. My editor was not happy, and the artist’s dealer was furious.

But I continued writing for that and other Chicago publications. At some point I was invited to be part of “CACA” — a self-deprecating acronym that stood for Chicago Art Critics Association. Its members included the late Kathryn Hixson, who was the editor of the New Art Examiner, plus an array of others that ranged from the traditional to the truly eccentric. When I left Chicago to work at the Guggenheim I wanted to stay a member, but for them moving to New York was the ultimate sin; so, I was summarily expelled from CACA.

Once in New York, I did try my hand again at art criticism, partially because I wanted to stay engaged with the Latin American art milieu. I contributed to Art Nexus for several years, with my favorite assignments being long essays on specific artists, as I did for Arturo Herrera.

While I was a trooper and always delivered (with the only exception of that aforementioned instance), I came to the conclusion that I really disliked conventional art criticism. I felt conflicted doing it as an artist, or at least in the terms in which I was required to do it, because I was much more interested in understanding art issues than handing a judgment on a work. The prescribed format of the art review frustrated me. Already then, my interests were leaning toward ontological exploration, and not into the game of validating or invalidating other artist’s efforts.

After those years, I started devoting my efforts at writing performance lectures as well as the occasional essay that dealt with contemporary art theory issues. For all intents and purposes, I had left arts journalism.

Or so I thought. In retrospect, I kept doing other forms of journalism through my career as a museum public programmer. I have written a in a past piece that I feel that I ran a newsroom for the art world, organizing conversations that pertained to current issues, even if we were dealing with historical art. After leaving the museum world, I missed those conversations, and thus was born Beautiful Eccentrics— a means for me to continue the dialogue, to refer to my sophomoric essay, but this time in the present tense.

The question in my mind remains on what can artists contribute to the field of journalism. About a decade ago, Creative Time (for full disclosure, I do serve on the board of that organization) made an interesting attempt to rely on the local knowledge of artists to create an online publication titled Creative Time reports. The project ran 316 pieces by artists in 58 countries until its close in 2017. Even though it ended after five years, it left an important model to consider on what is to be learned from artists perspectives, ranging from political realities to aspects of their ground work.

One way to look at that question is that the artistic practice shares affinities with journalism, primarily in the sense that if offers its on version of news analysis and commentary, which is embedded in artworks themselves.

Muntadas, a conceptual artist that I have written about before, and whose work has focused for decades on the subject of media, often keeps the TV on all day in his studio — usually in a news channel— but with the sound off. I never asked him why he does it, but in a way feels perfectly consistent with his work: the simple gesture of extracting image from sound in order to open the space for individual interpretation.

That is what interests me about journalism as an artistic tool: yes, I say, to the capturing of the daily event, but with the purpose of doing reflecting that might go beyond the gossip or the anecdote trying to elucidate not just what is happening, but why it is happening and what it might mean. Yes to using journalistic spaces as an open studio where thinking, imaginative flights of fancy, and close looking might bear some fruit— even if only to open another line of inquiry.

Note: The first annual Beautiful Eccentrics Conclave, this one to celebrate the 200th dispatch of Beautiful Eccentrics is this Friday, May 17th at 6pm at the Francis Kite Club in New York, and I’ve made a special artoon edition available to help support the project. Information here.