Laughing our Way to the Cemetery of Authoritarianism

This text was written for the September 2020 Issue of ASAP Journal from Johns Hopkins University Press, on the subject of Humor, edited by Jonathan P. Eburne.

In Bologna during the 1977 student movement, a popular slogan was “una risata vi seppelirà” ( a laughter will bury you all). The protesters, known as Indiani Metropolitani (Metropolitan Indians) were rebelling against what they saw as a conservative and rigid government., and their most effective weapon was irony as protest. It is speculated that Umberto Eco’s famous mystery “the Name of the Rose” of 1980, which revolves around a lost book by Aristotle on comedy and the condemnation of conservative monks on the subject, was in fact a response to the political climate of Bologna at the time (Eco was a professor at the University of Bologna).

I am often reminded of this fact during this Trump era, where the current US president displays a particular fixation with laughter. For Trump, the worst ignominy one can possibly suffer is being laughed at. His political career has been marked by his repeated warnings that other countries (such as China and Iran) are “laughing at us”. An address Trump delivered at the UN General Assembly in 2018 was met with laughter when he claimed “in two years my administration has done more than any other administration in the history of our country”. And it is believed that President Obama’s infamous put-down of Trump ( who was pushing for the racist “birther” conspiracy theory about Obama) might have been a great incentive for him pursuing the presidency a few years later.

Laughter is dangerous for someone like Donald Trump because it is powerful and immediate. Humor instantly undresses falsehoods and, through its various strategies, it can point to the absurdity and injustice of certain situations and speak truth to power. Earlier in Trumps’s term, the filmmaker and activist Michael Moore (who in fact predicted Trump’s election) also stated that the only way to defeat Trumpism is through humor (and has acted through this idea by creating a Broadway show titled “The Terms of my Surrender”). “humor is the non-violent weapon by which we are going to be able to turn this around”, he said in an interview.

The more urgent question for me in this moment is how humor can act as a political weapon in the high-brow echelons of contemporary art. As I have stated in the past, I believe that the visual art practice in general has always had a complicated relationship with humor. There is a dominating seriousness to the history of art, where drama and grand statements often take center stage (the Rembrandts, Velazquez, Delacroix of the world). Nonetheless, satirical works throughout history are powerful statements not only of the political and cultural moment but also greatly revealing of larger aspects of human nature (this is the case of Hogarth, Daumier, and the Goya of Los Caprichos).

In the XXth Century humor is utilized by some of the avant-gardes (in particular Surrealism and Dada) through the embracing of the absurd, and continues through the influence of artists like Duchamp in the works of Marcel Broodthaers and, I would argue, John Cage, who in turn influenced Fluxus. Pop Art is, in my view, also an inheritor of that kind of irreverence. Yet, upon a close examination, these various artists embrace a kind of humor that is less social critique and much more the exploration of the eccentricities of the self.

An interesting aspect of contemporary art practice is that, while it practices sarcasm and irony, humor is a much less present feature in many artists (Maurizio Cattelan notwithstanding).

Part of the complex relationship between contemporary art and humor is that it is a discipline in which it is important to create an aura of respectability and professionalism as a way to signal that the art presented is relevant and/or significant and not something that should be discarded offhand. This results in the existence of stiff social structures —many of which I have parodied in my own drawings.

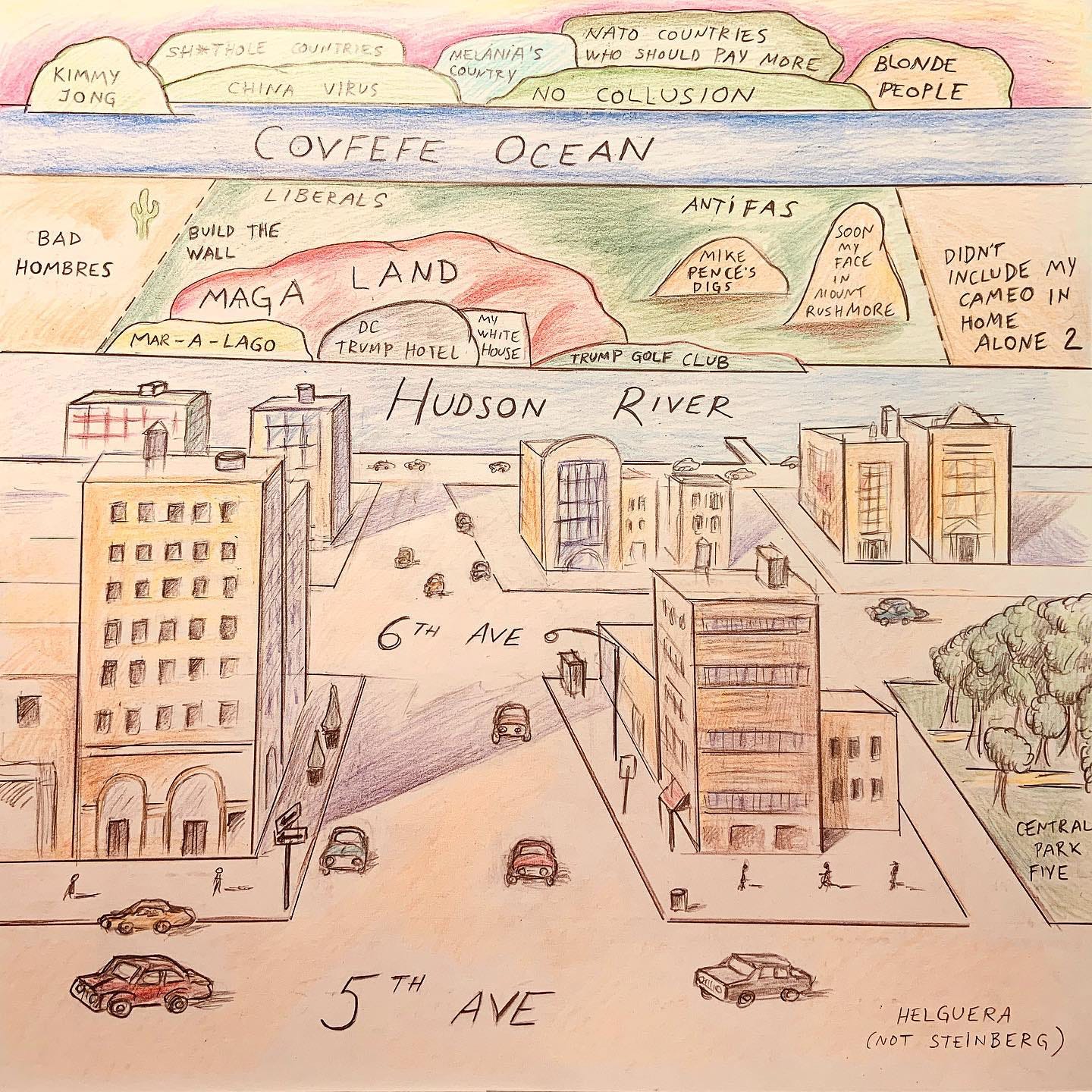

But somehow humor- and its most common artistic expression, cartooning- occupies a lesser place than the “serious” forms of art, ostensibly because these point at deeper, more significant issues. But is that true? I am not certain of it. I often look at the works of Saul Steinberg, who once described himself as “a writer to draws”. I think of the absence of this artist in the canonical writing of art history of the XXth century, where many of the artists of his generation (the Ab-Ex stars like Pollock, Barnett Newman, and de Kooning) take precedence over the work of this prodigious artist-writer. Yet, to me, his depictions of American society are more contemporary than Pollock’s grandiose gestural paintings. Steinberg’s depictions are existential reflections, small essays on human nature. They might not be things in themselves, as Pollock’s paintings are. But inasmuch as these images are pieces of writing, Steinberg’s works immediately make me think of deep philosophical issues around identity, our place in the world. His most famous drawing, “View of the World from 9th Avenue”, is a humorous but also deeply insightful view of the metropolitan provincialism of the typical New Yorker.

As an artist myself, and as someone deeply involved in presenting the narratives of XXth and XXIst century art to various publics, I have often grappled on the role of humor in my own work, and have even had conflicting feelings about it.

For all of my childhood and teenage years I spent most of my days drawing. Like all of my siblings, I had learned to read via comic books, Asterix, Tintin, and Mafalda (the great Argentinian political comic strip created in the 1960s by Quino). I invented a whole range of characters of my own of which I would create extensive comic-book stories.

When my grandmother took me to Guadalajara to see the murals of José Clemente Orozco, these were a revelation to me. The dystopian scenes depicted by Orozco at the Hospicio Cabañas, which were a strong condemnation of modernity—particularly the colonizing ideas of religion and progress— were deeply impactful for me.

Almost immediately after returning from my trip I started drawing muscular bodies engage in struggle, contorted beings amidst painful fighting in the fire and against giant and destructive machines. I really had no content in mind, and I was too young to have an understanding for a cause of struggle, but I still wanted my work to reflect “a” struggle, and embraced the idea that art needed to have a revolutionary impulse. This, of course, was my entrance into “serious” art making.

When I arrived to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 80s, I encountered other forms of political engagement shown in museums, —works by Barbara Kruger and Andres Serrano, for example, as we were amidst the culture wars of that period. The more work that I saw amidst my classmates was much more autobiographical. The school, mostly influenced by the spirit of the Chicago Imagists, greatly encouraged this kind of self-introspection. So we all endeavored to explore and expand upon our innermost eccentricities. My classmates used childhood toys, photographs, and sought to dig out images out of the darkness of their not so distant past.

We alternated our studio practice with art historical surveys and art theory classes. This time was the height of multi-culturalist theory and deconstruction. Foucault and Derrida were the basis of theoretical discussions, and we spent most of the days memorizing images of Romanesque, Baroque, and Rococo art works that we would then identify in exams and write comparative essays.

In all this, discussions about humor were almost nonexistent. Despite the influence of the imagists, which encouraged the incorporation of the vernacular and popular culture into art works (Ray Yoshida, for instance, would incorporate comics into his work, Roger Brown would make paintings that did resemble animated features, and so forth) but the results were not really humorous, but rather a form of late modern surrealism that was rife with psychological tensions and fueled by a kind of repressed energy that made the works intriguing, but not humorous.

As for me, I mostly stopped making cartoons as I started art school— I somehow, unconsciously perhaps, felt that I would not be taken seriously as an artist if I ever shared my cartoons with others.

But humor was, as I later realized, an inextricable aspect of who I was. More explicitly, this realization came for me in 2008 when I joined Facebook. I had the impulse of, instead of posting personal photos, to make a New Yorker-style cartoon (known as single-panels) about a topic that was very “insidery” for the art world intelligentsia. The cartoons about the art world -coined later by writer and curator Andras Szanto as “artoons”, took off and eventually came to define a good part of who I am as an artist — a part, I should say, that I have struggled to embrace as I continue to fear the gravitational force that makes illustration-based art fall into some kind of lower hierarchy against so-called “great art”.

However, in this political moment, when we are being witnesses to a global crisis of democratic systems, of the rise of authoritarianism and tyranny all over the world and the use of misinformation to control the public, I feel there is a renewed need for humor to play a role in art. We as artists are trained to create things and experiences that produce emotions, and unlike the average slapstick comedian, we can make these things and experiences mean more than a one-liner: we can construct them in ways in which they are longer reflections on issues that are central to our lives. This is the power of humor that I am always excited to utilize. In its best form, it is a time-bomb that enters easily into your mind, and if it accomplishes its purpose it can stay in your mind to make you reflect on the paradoxes or questions that lie at the core of certain societal attitudes. Satire today is powerful because it cannot be fact-checked, because it can’t be easily dismissed by authoritarians, and because, as small weapon as it is like the staff and sling of David against Goliath- humble tools that are capable of defeating the giant. The students of the 1977 movement in Bologna understood this concept, and it is one that I believe we need to fully embrace in contemporary practice today.