I live in an apartment complex in Brooklyn with a small courtyard where we often stop to greet neighbors and chat. A few years back one of them, Andrew (who I am very fond of and who sadly has now moved) started a conversation with me about AI and artmaking. Andrew wanted my opinion about an AI system that had recently composed a musical work (I think a “Bach” fugue), and whether AI might one day replace artists. I outright dismissed the idea as absurd, and we entered into a big debate about it. The main point I made to Andrew was that even while a bot might compose in the style of Bach it could not invent the style of Bach itself. AI, I argued, can’t do the fundamental thing that great artists do, which is to break with old paradigms and introduce new forms; it can only learn the algorithm established by a human and churn out results using those rules.

In retrospect, and given where AI is now, I see how arrogant and dogmatic I was in my initial response (I am sorry, Andrew!), and how much more complex the question is. As Steven Levy, editor-at-large of Wired Magazine recently said in an interview, “we have reached the point where code and coder are beginning to separate”. Ada Lovelace, the 19th century English mathematician who is credited as being the first computer programmer, believed that “only when computers originate things should they be believed to have minds.” In the 20th century, also in Britain, Alan Turing set that test for intelligence in a computer as the ability of a human to be unable to distinguish the machine from another human being by using the replies to questions put to both. By that standard, Levy argues, “I think these things run rings around the Turing test. I think they’ve aced this test and we are in uncharted territory now.”

There are many philosophical questions that AI-generated art presents, although I think some are more interesting than others. The most common (and in my view, less interesting) question in the AI-generated art debate concerns authorship. “AI is nothing more than sophisticated plagiarism” is a comment I read on social media recently. But that seems to me like a weak critique: isn’t all new great art a form of sophisticated plagiarism?

Further, this might only be a problem if we continue to embrace authorship ideas from last century. For years I have thought that the new conceptual artists (most of which might be surprised to be called such) are really those who invented the interface systems we all use to create in the first place. One of them is the 35 year-old Mira Murati, a computer engineer and Chief Technology Officer of Open AI who led the team that created ChatGTP. Murati might not be an artist, but the creation of art-generating platforms does not seem too different to me from the creation of a particular set of conceptual principles/scores/instructions that later lead to artworks.

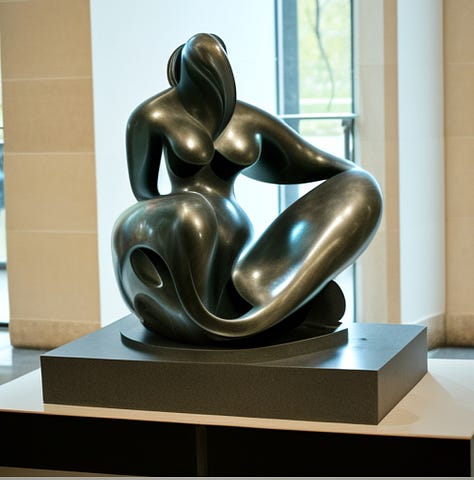

Another more interesting, but not as key (to me) question has to so with the so-called “authenticity” of AI-generated art. This topic is now the rage in mainstream journalism: for instance, Adam Gopnik recently wrote in The New Yorker that AI images are more attractive than AI prose, pointing to a credible Charles Demuth-style watercolor that he had made using the DALL-E 2 system. Only that there is no technology (yet) to physically make/plagiarize paintings or drawings. In other words, no AI can forge a physical painting that will fool even the average viewer, let alone experts. I hasten to emphasize: yet. We do now have AI generated sculptures that could easily fool a viewer as the actual works of a particular artist. It only took me two minutes to make the following Miró, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth sculptures which I could theoretically have 3D-printed and exhibited: while I grant that they are not entirely convincing, what if I (or more technologically-savvy forgers) were to spend a month doing this?

The aspect that interests me the most about AI-generated art is one that I thought about the other day when I saw yet another neighbor in my complex, Ignacio Ayestaran, an accomplished professional photographer and 3D artist working in the commercial industry for the last 20 years who has received many awards, including an Emmy for his work on the Discovery Channel. Ignacio (who goes by Nacho) showed me the work he has done using the AI system Midjourney, which he presented at a lecture this week. Nacho has a specialty in lighting, so he is able to create astonishing effects with this system.

Interestingly, Midjourney struggles in places where most painters also typically struggle, such as in the rendering of human hands (“these ones look like potatoes”, Nacho remarked in a series of images of an old sailor he was trying to generate, partially based on a photo his dad had taken in Portugal in the 80s). But what interested me the most was how Nacho aided the program by feeding it source images and fixing aspects of the results in Photoshop (as the system sometimes gives results that are incongruous or strange).

Ayestaran’s images and process made me think about a crucial process, not just in AI but in art: research, sourcing and emulation. All new art builds from pre-existing historic works, both establishing a dialogue with them but breaking new ground. However, there are some periods that foreground the sourcing, such as neoclassicism. And in fact, this is only part of something that is already happening in 21st art where the idea of formal/aesthetic “movements” are giving way to a kaleidoscopic set of practices that draw from practically every historical moment— a critical emulation or old art forms using large language models (a term designated for computer programs for natural language processing that use deep learning and neural networks) and AI can only help us develop this chapter of art better. I will explain, with the mention of two important examples (one interpretive and artistic, another technical) of what I would term deep-sourced art language-learning.

After the deeply transformative year of 1913, which marks key moments of the avant-garde such as the first performance of Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, one of the most important musical compositions of the 20th century, several artists shifted toward a period in pursuit of a neoclassical aesthetic. Between the years 1917 and 1925 Picasso abandons synthetic cubism and shifts to producing works with figures with classical dress and sculptural forms heightened by a Renaissance-influenced form of shading. As to Stravinsky, in 1919 Ernest Ansermet wrote to the Russian composer telling him that Sergei Diaghilev (the impresario and founder of the Ballets Ruses) wanted a ballet based on an 18th century Commedia dell’arte libretto attributed (wrongly, it now seems) to Pergolesi. Stravinsky was not interested initially, but later got into the idea and composed Pulcinella, a ballet based on Baroque-era musical themes but with the experimental harmonies, rhythms and cadences that are vintage Stravinsky. Of the experience he wrote:

Pulcinella was my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible. It was a backward look, of course—the first of many love affairs in that direction—but it was a look in the mirror, too.

And second example: In 2004, Jon Ippolito, new media curator at the Guggenheim Museum, organized an exhibition titled “Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice.” Ippolito, who joined the Guggenheim in the 1990s when new media dominated the contemporary art discourse, proposed the Variable Media Initiative, an important set of practices to help conserve artworks made in emerging media (primarily digital) formats. I believe Ippolito was one of the first people to ask questions regarding how museums can collect and preserve art made on ephemeral technologies, websites, old computers or software. The Guggenheim exhibition presented a series of works in their original technology next to a replica of the work made in a state-of-the-art technology (except that in this case it would have been programmed to “behave” like the old technology). One work in the show was a video piece by Grahame Weinbren and Roberta Friedman, The Erl King (1983–5), which is considered one of the first interactive video works. The work had a touchscreen monitor that would allow the viewer to control the narrative of the piece.

I mention these two examples that are a century apart because, while very different, they are cases (artistic and technical) of the resourcing of old aesthetics, techniques and methods that have always been part of the art practice even during times that purported to destroy all previous paradigms (Stravinsky playfully adapted his composition style to simulate Pergolesi’s in order to make something new). It is a process that it is always there, but only surfaces and becomes more explicit during particular periods, such as with postmodernism where contradictions are flagrantly —sometimes even ironically— presented and celebrated. As Learning from Las Vegas author and architect Robert Venturi once said, “Viva ambiguity acknowledged unambiguously!”

I am actually very interested in the works of artists who rigorously pursue old art forms to produce new works, such as Kehinde Wiley and his equestrian portraits. Wiley can adapt his technique to the neoclassical style of artists like Jacques-Louis David. His work is not a mere imitation of a historic artistic style, but a conceptual appropriation both technically competent and innovative—in his case, a self-portrait that addresses current issues of heroic masculinity and race. He exemplifies how many contemporary artists are not only fully conscious of the history before them but are able to draw from that history in a critical and innovative manner, and deep without it feeling like a nostalgic exercise. This is what I mean by “deep-sourced art language learning.”

So isn’t AI more like a mainstream expression of what we all have been doing in art over the last 20 or so years? In his introduction to his 2002 book Postproduction, Nicolás Bourriaud writes: “how can we produce singularity and meaning from this chaotic mass of objects, names, and references that constitutes our daily life? Artists today program forms more than they compose them: rather than transfigure a raw element (blank canvas, clay, etc.), they remix available forms and make use of data.” In a sense then, AI is now the best ally for artists to meet this purpose. But also, while AI is a game-changer in some ways, in practice it is right now a bit old-fashioned: post-postmodern.

Now, going back to what my neighbor Andrew feared: will AI replace artists? For now it already seems like it will obliterate, if not completely transform, the stock photo industry. But will it one day be able to reach the point where it not only serves as a tool but also introduces new paradigms with a critical eye and even irony? These are unanswerable questions at this moment. This week Noam Chomsky wrote the most recent scathing critique of AI —in his case, ChatGPT, concluding: “Given the amorality, faux science and linguistic incompetence of these systems, we can only laugh or cry at their popularity.” However, he does not entirely discard the possibility that one day we will witness “the first glimmers on the horizon of artificial general intelligence— that long-prophesied moment when mechanical minds surpass human brains not only quantitatively in terms of processing speed and memory size but also qualitatively in terms of intellectual insight, artistic creativity and every other distinctively human faculty.”

In the meantime, I have given into the temptation and created my (my? their? our?) very first AI images for this column. And I will continue to create my own art works until (and likely after) we, the archaic authors of human-made art, slowly fade into obsolescence.

Fascinating commentary. Thanks!

A great read, thank you.