Life in the Conceptual Wild

Elusiveness as an artistic medium.

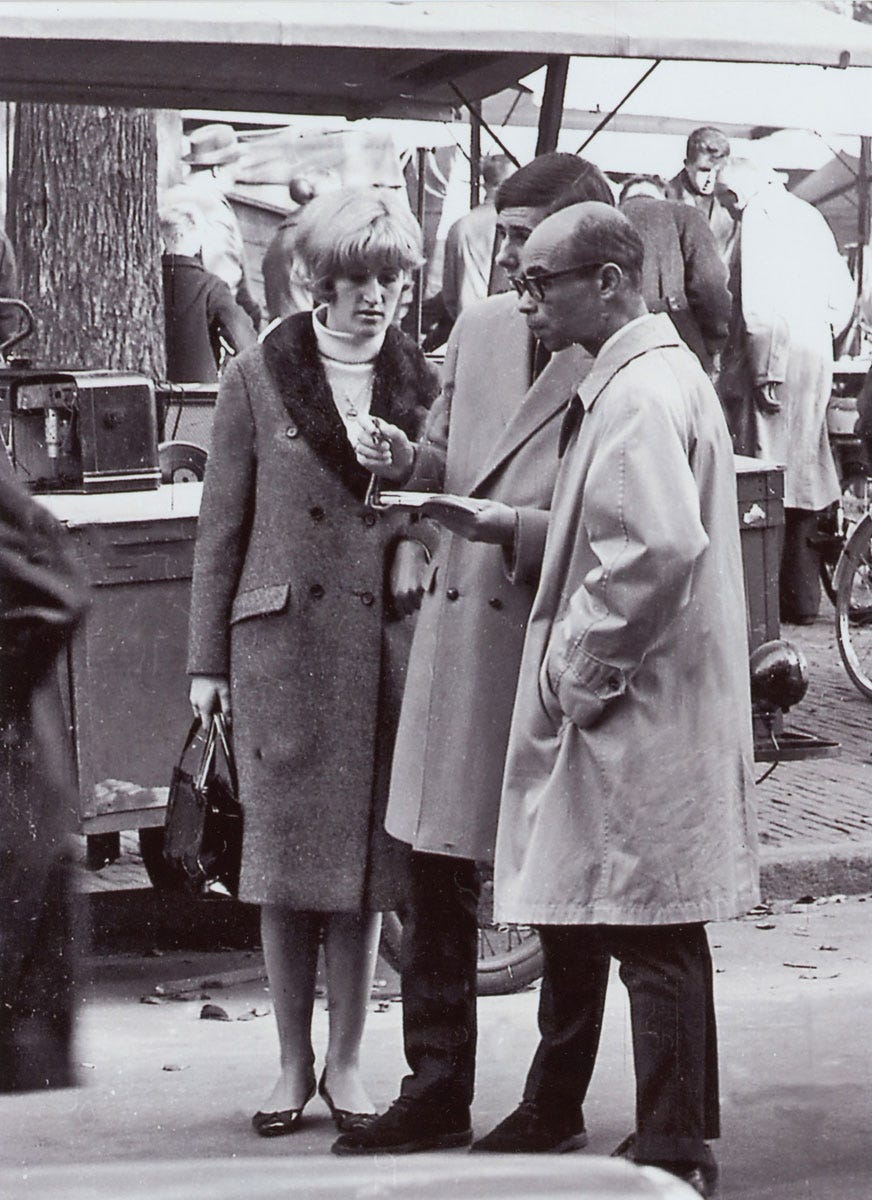

Stanley Brouwn asking for directions, 1960s. Photo: Igno Cuypers/ Fondazione Bonotto Collection.

Back in 1999, I mailed a letter to the legendary MoMA Curator Kynaston McShine to invite him to be part of a panel discussion I was organizing in Mexico City titled “Lo ficticio dentro y fuera del museo” (Fiction Inside and Outside the Museum). I had just seen McShine’s major institutional critique survey “The Museum as Muse” at MoMA and felt that the topic of fiction was all interwoven throughout it, given the ways that artists appropriated the form of the museum to make fictionalized institutions.

Kynaston was intrigued (looking back, he was probably amused by and curious about my youthful ambition and naiveté) and invited me to lunch at MoMA to discuss my idea further. At the lunch, I remember asking Kynaston why he had not included the Museum of Jurassic Technology in his show (which to me appeared to be a major omission given the postmodern subject). He then replied that he was very much aware of David Wilson’s museum but that he “just didn’t know how to fit it into the show.”

McShine’s comment was something that in fact I have seen reemerge in conversations many times over the decades: a curator interested in an artist’s practice and desiring to support it; however ultimately unable to do it because of perceived or actual constrains in their exhibition or curatorial model.

The easy way to critique this position is to say that this is a failure of the curator or the institution, but the problem is more complex. In the case of the MJT, David Wilson is extraordinarily reluctant to be categorized as an artist and/or his museum as an art work; which creates problems when trying to fit them into a conventional exhibition (although this is not to say that the MJT did not participate in group shows; it did, including one, in fact, that I myself curated in Chicago in 1998 titled “Concerning Truth”. It took some convincing, but ultimately I was able to create a curatorial premise that ultimately satisfied Wilson).

The issue is simply that some artists and art works like (or need) to live “in the wild”, that is, in the margins of definitions and categorization. The reasons for that choice are also difficult to determine; they may not merely a desire to provoke (I remember an artist I know a few years ago attempted the “play hard to get” game, sending group emails to many of us full of cryptic, arrogant and contemptuous comments, thinking perhaps that this attitude would make him interesting. It did not generate interest, and most of us unsubscribed from his emails that were a combination of insult clown performance and need for attention).

Instead, the artist from the conceptual wild, while they might enjoy the teasing they provoke in many of us, they are truly slippery, and most likely, they have a natural condition that simply can’t be artificially fabricated: a combination of shyness, obsessiveness, and eccentricity.

One of the artists that best exemplifies this slipperiness in my mind is Stanley Brouwn. Brouwn was born in 1935 in Paramaribo, Suriname, the smallest country in South America — a country mainly populated by descendants of slaves and laborers brought in by the Dutch.

When he was 22 years old, in 1957, Brouwn relocated to Amsterdam where he soon became associated with the Zero Art Movement — a group formed by artist Otto Piene and Heinz Mack and later joined by artists like Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely and Daniel Spoerri. Besides their interest in the creation of kinetic sculpture and perceptual experiments, their emphasis was decidedly anti-subjective, arguing for ‘a zone of silence [out of which develops] a new beginning’. Soon he veered toward a radical form of conceptual art. In 1960, Brouwn declared that all the shoe stores in Amsterdam were a work of his. Then in 1961 he produced his most famous series of works: This Way Brouwn, consisting in asking passersby for street directions and asking them to draw the directions on a piece of paper; the resulting drawing would later be claimed by the artist as his work, stamping each piece with a rubber stamp that said, “This Way Brouwn.” He also included blank pages of instances where the passerby had not drawn anything when they did not know how to provide the directions.

But aside from his conceptual work, or perhaps as an extension of it, Brouwn became known for his insistence in being invisible, which might be a legacy from his involvement in Zero. He generally would not allow his work to be reproduced, his photograph taken, or any biographical information about him be shared (to this day, it is hard to know if he was ever married or left any children). And he was very hard to find, only showing up whenever people least expected it. Yet for all his self-effacing-ness he was still included in four Documentas (5,6, 7, and 11) and his work is in some of the top collections in the world. He was one of the most famous elusive artists of the 20th century.

David Hammons has cultivated elusiveness as a medium for a while, becoming a holy grail of sorts for any contemporary art curator who wants to do a major exhibition of his. The recently deceased Colombian artist Antonio Caro had a similar reputation for being impossible to pin down for a meeting but at the same time would show up everywhere—like most great artists, he could only be an artist in his own terms.

Then there is conceptual elusiveness, which is a slight variation of this artistic genre. The Museum of Jurassic Technology and Salon de Fleurus, both projects about which I write about often, are of course primary examples.

Some artists create works or model behaviors that, as unnerving they might be for their unpredictability, for escaping categories, and for writing the rules of engagement entirely in their own terms, produce also complete fascination, as their antics operate sometimes as some kind of seduction mechanism. Another good example of a conceptually elusive artist is Dahn Võ whose biography provides the context for his artistic approach. At 4 years old he was put on a boat by his father to flee Vietnam to go to the US and was rescued by a Danish shipping company, thus eventually getting him to Denmark (he is a Danish citizen today). While being registered by the Danish authorities, his middle name, Trung Kỳ, was recorded as his first name. The family name Võ was placed last. Võ once said “I’m very childish. When people want to put me in boxes, I go the other way.” Vo’s conceptual approach indeed always goes against the grain to what is being expected (which is not a new thing among other conceptual artists), but in his case surprises can be extreme. As part of a legal fight with a collector who claimed that he had been promised a new work by the artist, Vo proposed to have a work installed in the collector’s residence telling him to “shove it”.

Then there are those artists who prove difficult to pin down, not because of their absence, but precisely and ironically because of the opposite— the fact that their mind seemed to be in so many places that they could easily overwhelm anyone: I am thinking about James Lee Byars. I asked curator Luis Croquer, who researched Byars deeply for many years, about this. According to Croquer, Byars “was an artist that intentionally and constantly pitched projects and that had a ‘target’ list: Thomas Messer at the Guggenheim, Dorothy Miller at MoMA, Wie Smalls in Holland, Flor Bex in Belgium, and others. He inundated them with letters. They all believed in him but some were put off by it. Messer is allegedly reported to have said: ‘Byars is an artist that I’ll work with when he is dead’. Having said that, they all helped him.”

Interestingly, Byars shared a similar interest with the artists I have mentioned around the control of his biographical narrative (either by depriving the public from it or by curating it in particular ways). In his case, Croquer adds, “he also was adamant in controlling the narratives of his work and did it like it to be historicized or contextualized. That’s why there are such few catalogues or texts about his work from his lifetime. Byars was trying to work in the early period outside of formats so a lot of his work lived in anecdote or mythic space ( the later Byars is different). He invented a persona and lived it through and through that’s why he’s so far to pin down. To me that’s a proof of success but also a challenge because he is misunderstood.”

And last but not least there is elusiveness in the more traditional form of reclusiveness— a trait that would deserve an entire book, let alone a column.

In this regard I can just share a small personal anecdote regarding one of those artists, who at least for one period of her life sought to live in anonymity: Leonora Carrington. Like most of us in the Mexican art world (and elsewhere) I was always a big fan of Carrington and always wanted to meet her one day (which sadly never happened). In the 1990s, a period during which I lived in Chicago, I happened to look at the metropolitan section of the Chicago Tribune newspaper, which had a rather boring article about senior citizens learning how to drive. The photo illustration of that article, however, shocked me: it was Leonora herself on the driver’s seat of a car, with a caption to the effect of: “Leonora Carrington, from Oak Park, IL, getting ready for a driving lesson.” Clearly the reporter had no idea who Carrington was.

Years later I learned that Carrington lived for a period in, of all places, Oak Park, Illinois (a suburb of Chicago), during the 80s and 90s — first permanently and later supposedly, as I was then told, to visit one of her sons who lived there. I thus lived for years in the same city where she lived without knowing it (as well as the local art scene, who I am sure would have made a big deal of that fact). In the 1990s Carrington attended a Focusing group in Oak Park ( Experiential Focusing is a mental practice used to gain deeper self-knowledge and healing) and for years, according to its members, no one from the group knew that she was a famous artist.

Elusiveness in artists and their artworks, be it due to a calculated strategy on their part or not, presents an interesting challenge for the curatorial practice and for the art historian. First there is a question around the artist’s intentions: if the artist believes in the importance of the artwork not be connected to them in biographical or other terms, shouldn’t this wish be respected? The problem becomes more complex when they openly declare that their work is not art anymore, as Lygia Clark did shortly before she started her therapies. And going back to James Lee Byars, what to make of his famous declaration “I cancel all my works at death”? Is the declaration itself an artwork, and as such, should it have the real (i.e. legal) consequences of rescinding authorship? Paradoxically in cases like these, when the artist has really left an indelible mark in the world, it might not be possible for them to have it erased through a simple declaration. In the same way that the strangers coaxed by Stanley Brouwn to draw directions did not know they were participating in a conceptual art piece, artistic legacies might not be something from which any great artist can ever escape.

I'd like to add artworks that are not ever publicized. The wonderful Australian artist Charles Green (who paints and photographs with his partner, Lyndell Brown) did a series of actions decades ago that involved walking to the top of a mountain and sitting still for a number of hours. He mentioned this in context of a book about his work, where those actions are mentioned for the first time. When he did them, he intended never to document them or mention them to anyone. Did Richard Long ever go for walks without taking photographs or making things, and without mentioning it? Did On Kawara visit places he never documented?

...and Gino De Dominicis! :-)*