This summer I was invited to do a bit of consulting work for an exhibition at the Mitchell Art Museum in Annapolis of the work of the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. An interesting thing happens to us, art educators, whenever we are assigned an exhibition subject: we will work on any topic whether we like the artist(s) or not, whether it is a big art historical name or a totally unknown artist or obscure art movement. It is perhaps like being a surgeon: you operate on whatever human body, regardless of who that person is. When the artist is hugely famous and a familiar art historical reference you might think that there is nothing more to say or add about them, but what I have learned is that whenever you revisit old and familiar material you always find interesting angles and topics to which you had not given too much thought before. Such was the case over these past few weeks with me as I went back to revisit old Posada.

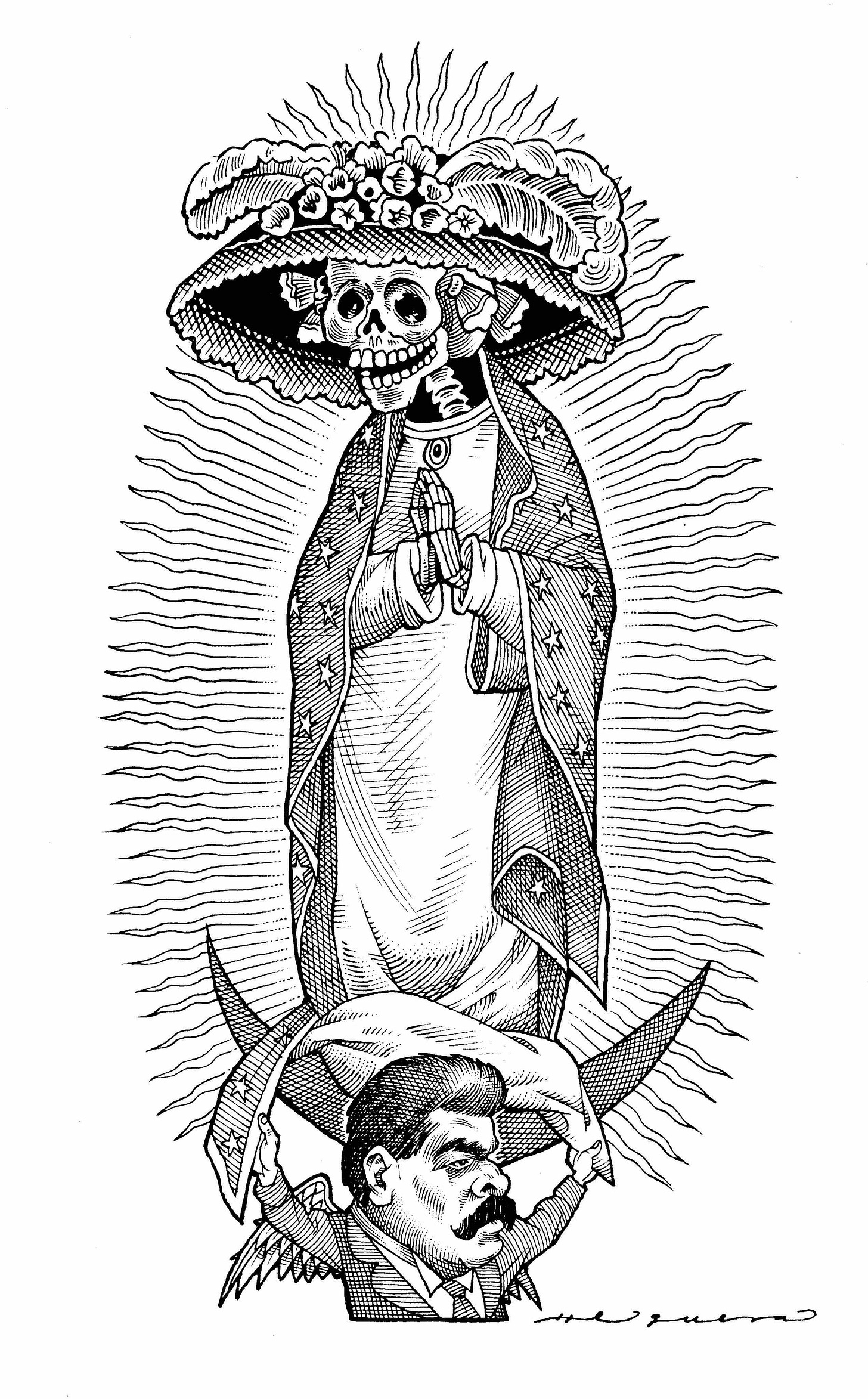

While Posada during this lifetime was not considered a “fine artist” (as per the definitions of what a fine artist was supposed to be in the 19th century), his name is today one of the most recognizable in Mexican art and he is considered one of the most influential Mexican artists of the 20th century, as well as one of the very few artists whose works entered the Mexican popular consciousness. His Calavera Catrina is one of the most recognizable images in Mexico and a constant reference for folk artists, Day of the Dead celebrations and popular culture in general. And beyond: the makers of the 2017 Pixar film “Coco” used Posada’s drawings, including the Calavera Catrina, as a key visual reference.

Posada was born in Aguascalientes, a city in the northwest of Mexico, in 1852—shortly after the end of the US/Mexico War. He studied drawing in a local art academy in Aguascalientes, but his true education took place as an apprentice in the workshop of the artist José Trinidad Pedroza who taught him lithography and engraving.

The art that dominated during Posada’s youth was a belated form of neoclassical painting that followed the models of the French Academy. While Mexican artists like José María Obregón were searching for a form of national narrative, drawing from Pre-Columbian examples and revaluing indigenous history, the compositions and technique were firmly following the school of Jacques-Louis David, a set of formal and narrative rules of half a century prior. Posada would take a different route.

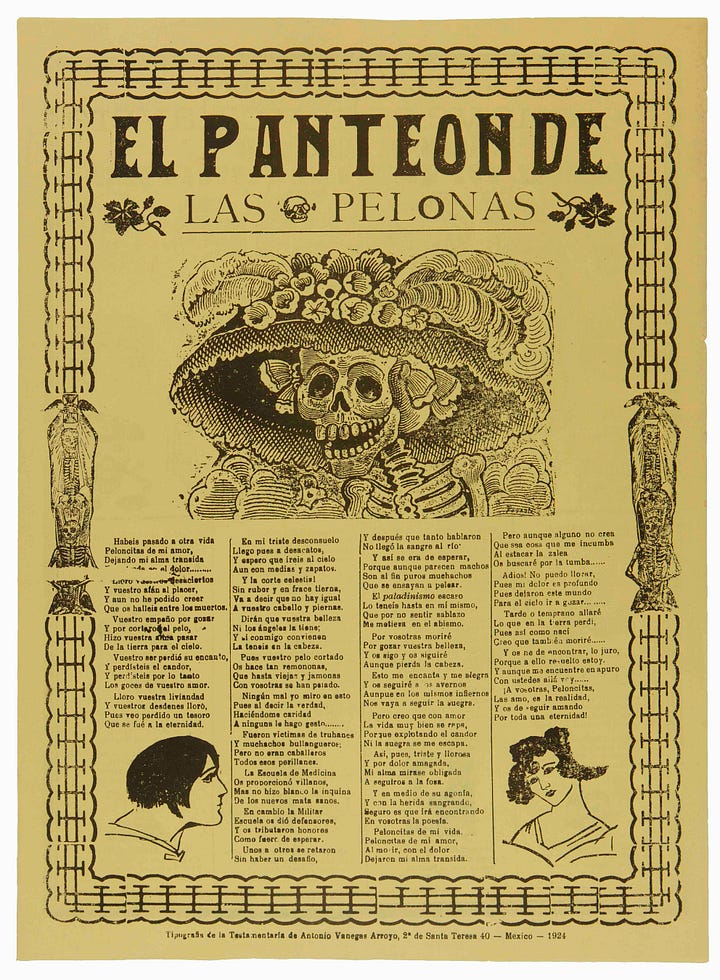

Posada’s apprenticeship with Pedroza put him on the path of becoming a printmaker and illustrator. In Mexico during the 19th century literacy was under 20% in the national population, which meant that only 2 out of every 10 Mexicans knew how to read. This very fact made illustrations even the more important for any printed piece, and thus the job of the illustrator was key. Posada illustrated pamphlets, broadsides, chapbooks and news articles; he did political cartoons and illustrated stories that we would now call tabloid or yellow journalism ( Phenomenon: Child born with a face in his butt! Mother gives birth to three diabolical beings! ) to news of tragic events and those of the Mexican Revolution (which he documented during the last three years of his life).

The two most famous portraits that circulate around Posada is the photograph of himself standing outside of his own engraving workshop and a print by artist Leopoldo Méndez of Posada observing the violence of the civil unrest in Mexico from his work table. Mendez’s portrait makes the point that Posada was an observer and a chronicler of everyday life in Mexico in all its aspects of celebration, tragedy, and oddities. He was a painter of modern life, maybe not exactly like the one the Baudelaire described in his famous contemporaneous essay, but certainly fitting to one of Baudelaire’s famous quotes: “beauty is always bizarre.”

There are at least two main aspects about Posada that can offer interesting discussion topics around an artist’s cultural legacy.

The first, which is the common aspect dealt by art history, is how an artist working outside of the sanctioned academic forms of art can end up being much more consequential than those who worked within that structure, even those who excelled in it. When the Mexican muralists looked for a visual vocabulary that was authentically representative of Mexican culture, they did not pick the Jacques-Louis David emulations with Pre-Columbian themes, but Posada’s skeletons: Posada was a clear artistic lineage to them; so much so that both Rivera and Siqueiros portrayed Posada himself in their murals as a revered artistic ancestor.

As to Orozco, in the 1890s and on his walk to school he reportedly would observe Posada at work through the window of his print shop in Mexico City. Orozco also started his career as a cartoonist, and his form of satire and social commentary has the unmistakable influence of Posada. Of Posada, Orozco recalled: “This was the first push that set my inspiration in motion and impelled me to cover paper with my earliest figures; this was my awakening to the existence of the art of painting.” In the 1920s art critics and authors lionized Posada. Anita Brenner described him as “The Mexican Prophet” and in 1925, Frances Toor in the publication Mexican Folkways described him as “the greatest artist produced by the Mexican Revolution”, adding: "his engravings crystallize all the stirring events of those days: ---the inevitable struggle of the middle class against feudalism and the reaction of the masses to politics, sports, miracles, crime, the parasitic church and budding imperialism." Later, Justino Fernández would note how Posada’s “expressionism” rendered the dominant naturalism of academic art obsolete.

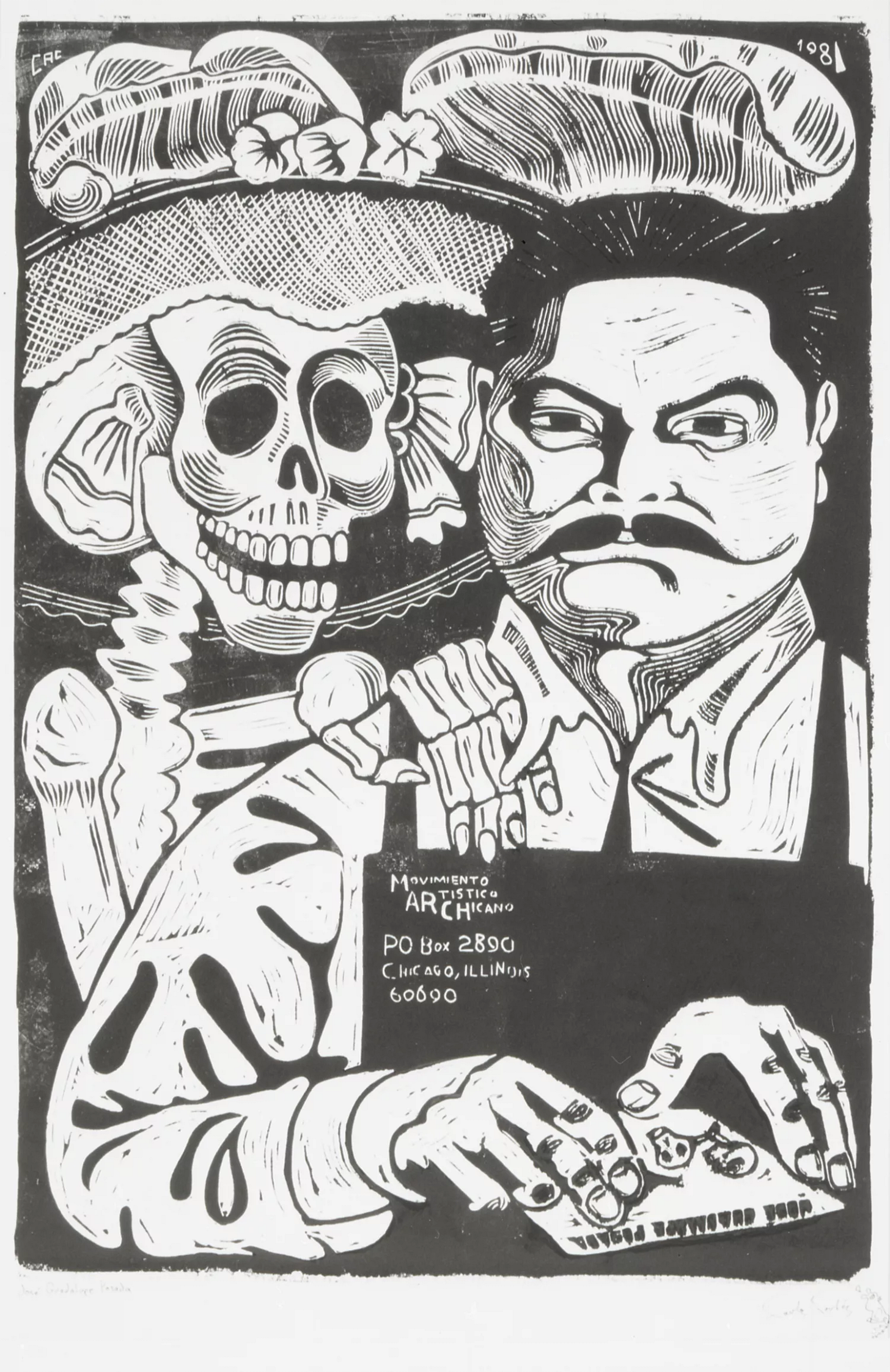

Precisely because of Posada’s popular appeal outside of high art, his presence has become ubiquitous not only in popular crafts (in ways that you would never see other artists with the exception of Frida adopted) and as I mentioned, by Hollywood, but more importantly, by Chicano artists, who saw Posada’s commitment to social causes and his ability to use his craft to document political struggle as a big inspiration for their movement. The examples are endless, but on a personal note I often think of Carlos Cortez (1923-2005), a revered local Mexican-American artist who I knew during my years in Chicago, himself a printmaker and radical Wobbly activist who believed art should not be a commodity but a common good (he instructed for his print editions to be unlimited so that the individual prints would never reach an inaccessible price). In 2002, Cortez edited and wrote the introduction to the book Viva Posada: A Salute to the Great Printmaker of the Mexican Revolution.

But the other, less explored aspect that Posada’s life and work offers for reflection is the question of what kind of perspectives can an artist offer when acting as a journalist or chronicler. It is of course a very important question for me these days, as the act of writing this very weekly column for the last three years has involved a degree of research and light reporting. At first glance, the relationship between artists and journalism would seem incompatible due to how both fields engage with the present: journalism is as is known the first draft of history; art is expected to offer a long view that goes beyond the daily event. This is perhaps why cartoonists and illustrators tend not to be viewed (unfairly, I might add) as “real” artists. I recall when the legendary maverick Robert Rosenblum curated the Norman Rockwell retrospective Pictures for the American People at the Guggenheim in 2002 (when I was working there) the art world cringed. But Rosenblum’s show did drive home the point that this work, while not considered part of the modernist canon, was indeed part of 20th century art history, as Posada’s also is.

Posada’s legacy can be found in quite a number of Mexican artists who later worked with and for the press, including the polymath Miguel Covarrubias who was famous for his illustrations for the New Yorker, the cartoonists Abel Quezada and Rius, who was also an educator and used his talent to create extraordinary comic-style books introducing the Mexican public to various subjects. Posada’s influence extends to contemporary political cartooning in Mexico. My very own late cousin, Antonio Helguera (1965-2021) who tragically passed away two years ago, was a noted political cartoonist in Mexico, who made a tribute to Posada in one of his images.

The relationship that Posada modeled as artist-journalist arguably extended to other forms beyond political cartooning in Mexico. I think of the practice of photojournalism, which is very important in Mexico and which includes photographers who became recognized as artists in their own right such as Enrique Metínides (1934-2022) who, like Posada, often documented tragedies and accidents that would appear in “nota roja” publications (usually translated as yellow journalism, or tabloid press).

Then there is the question of the kind of contribution that artists make in the form of writing. I always remember a conversation with Celia Sredni de Birbragher, publisher and founder of Art Nexus magazine, when she told me, “visual artists seldom write, but when they do, they write very well.” In contemporary art, we do have a genealogy of many artist writers (Donald Judd, Dan Graham, Luis Camnitzer, Andrea Fraser, Coco Fusco, Hito Steyerl, Hannah Black, etc) and a very interesting experiment a decade ago in this area was Creative Time Reports (2012-2017), a project that sought to put artists at the center of journalism- providing dispatches from different cities and speaking not necessarily about art but also about the social and political events on the places where they lived and worked. Their first post was a piece by David Byrne’s “Will Work for Inspiration”, which was co-published with the Guardian. I asked about the initiative to Laura Raicovich who was Director of Global Initiatives at Creative Time and who oversaw its launch. According to Raicovich, “ So many different geographies became connected through the project, and I began to understand much more deeply that while the meta, structural issues faced trans-continentally may be playing out hyper locally, we have so much to share with one another about how we cope, survive, and even thrive.” She how runs a monthly publication titled Protodispatch which is partially inspired on the model once explored by Creative Time reports.

When I asked Raicovich what was the toughest part of the experiment she replied: “The toughest thing about it was to explain to media outlets that artists had takes and did research that should be considered more broadly and not in the art section!”

Which makes me think precisely of how the mainstream writ large —not just the media mainstream but also the academic one— tends to place and isolate the artistic practice, sometimes with the goal to turn it into a commodity, sometimes to render it a merely decorative plaything. When it breaks its assigned boundaries, the status quo disapproves or feigns indifference. But for artists all roads lead to Rome, and journalism is one of them.

Thanks for this. Here in the SF Bay Area Posada is a graphic touchstone for most Chican@ graphics artists. You comment that "cartoonists and illustrators tend not to be viewed (unfairly, I might add) as “real” artists" but even more broadly, social justice poster artists get little respect from the "art world." But then, respect isn't what they are looking for.