Made (and erased) in Mexico

What the erasure of hand-painted commercial signs in Mexico City uncovers.

Food stall in Delegación Cuauhtémoc, CDMX before and after (Rótulos Chidos/Pintura Fresca)

Mexico City, July 7, 2022

The famous opening paragraph of Borges’s El Aleph is a comment about a cigarette advertisement that is taken down in Plaza Constitución. The narrator, who is mourning the death that very day of his beloved Beatriz Viterbo, is pained to see the ad be taken down “because I understood that the incessant and vast universe was already distancing from her and that this change would be the first of an infinite series.”

Over the many years I have been away from and sporadically returned to Mexico City, signage is a way by which I have measured the passage of time, and, like the character of Carlos Argentino, I often lament the instances when I find that a familiar advertisement has been replaced or painted over. Commercial signage becomes an interesting form of urban marker and some can also become cultural referents to a whole generation. In the case of mine, one of them was the “México calza Canadá” sign in the Tacubaya neighborhood, now gone.

Zapatos Canadá sign, on the Edificio Ermita (designed by Juan Segura in 1931) on the corner of Revolución and Jalisco avenues in Tacubaya in the 1980s.

The small-scale register of the constant becoming of a capital like Mexico City is most visible in the rótulos (hand-painted street signs) of its thousands of food stalls—, colorful images on the businesses that serve tacos, tortas, juices and a myriad other food products. The topic has become prominent now in Delegación Cuauhtémoc (a borough in Mexico City) where a few months ago its mayor Sandra Cuevas ordered them to be painted over, supposedly to “clean up” the area and give it a more modern look. The food stall vendors were forced to pay the city to have them paint their signs over and replaced by a drab grey logo of the delegación. Emulating the Byzantine emperor Leo III who forbid the painting of religious icons, this mayor decreed the erasure of the rótulos of all taco and torta stalls.

Sign by Fer Ayala (“The political class does not decide what art is”), 2022 @el_fer_ayala

Mexico’s artistic community has unanimously joined in the protest of this draconian measure, which really is an ignorant assault against a rich form of popular art that gives the city a unique character. The decision also affects the professional rotulistas (the sign-makers) whose livelihood depends on the ability to make signs for these businesses.

Shortly after the unpopular erasure order by mayor Cuevas, an organization comprised of various graphic designers named @re.chida (Red Chilanga en Defensa del Arte) started an Instagram archive of the many hand-painted signs in Delegación Cuauhtémoc, both as an act of protest and as an effort to preserve the memory of these images.

Among the many other critics of the mayor are the designer Juan Carlos Mena and editor Deborah Holtz, who together in 2000 assembled the editorial and exhibition project ¡Sensacional! (still on tour today) that documents the rich history of hand-made signage in Mexico. In a recent interview with both of them on the topic of the delegación Cuauhtémoc’s erased signs, Holtz said: “what this woman did is totally irrational” and speaking of the food vendors and the way they are not allowed anymore to represent their business through colorful branding, it is “a violation of the rights of these people.” Juan Carlos Mena adds: “to say that those images are ugly is pretentious and arbitrary. These signs have become part of the city. To paint those businesses over only enhances the ugliness of the city.”

Throughout the 20th century there has been a long fascination by artists around commercial signage, starting with Cubism. The integration of texts in the Cubist compositions of Braque and Picasso onto a flat plane has been associated with the way in which one would see scenes of a café through the window of the establishment that bears its painted letters on the outside. Duchamp’s famous Apolinère Enameled (also known as the “Impossible Bed” painting) from 1916-17 is a further example of an artist incorporating (and in this case, heavily altering) existing commercial text to make a work. In Mexico, artists like photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo drew from the Surrealist interest in re-signifying commercial advertisements.

Marcel Duchamp, Apolinère Enameled, 1916-17, Gouache and graphite on painted tin, mounted on cardboard, (9.6 in × 13 in) Philadelphia Museum of Art

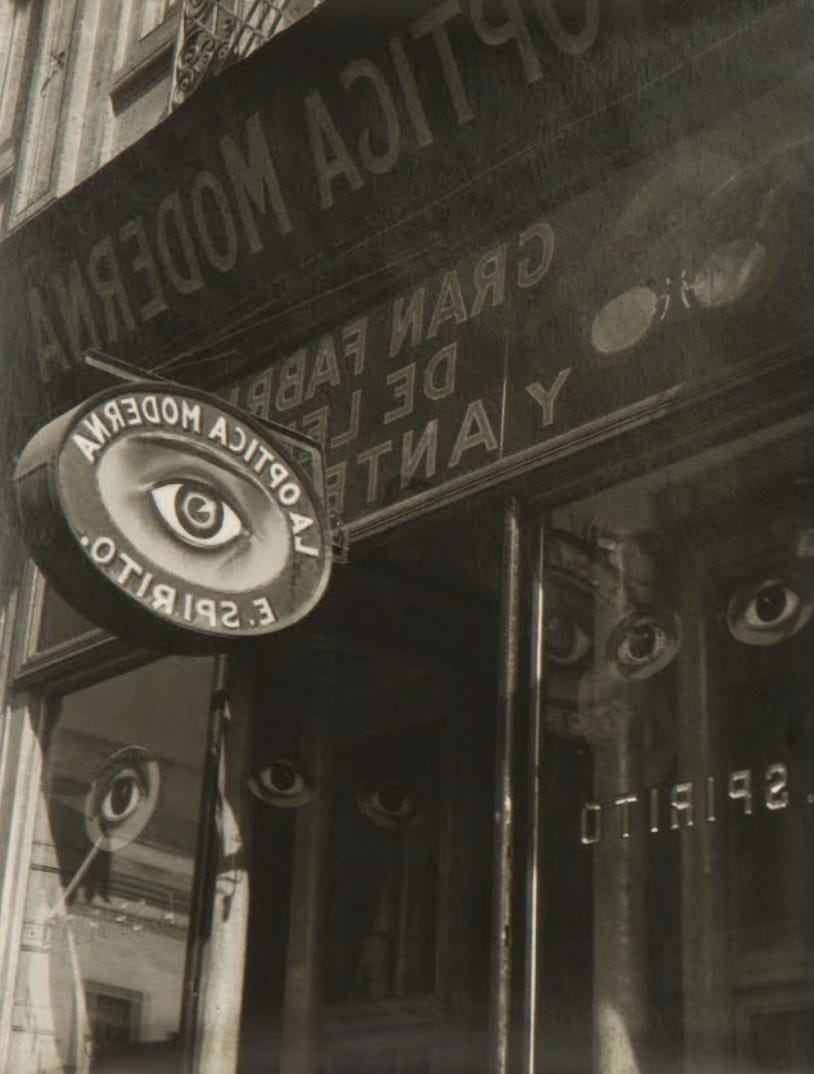

Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Parábola Óptica, 1931, gelatin silver print, 9 3/5 × 7 1/10”

Pop art is obviously the ultimate consequence of that exploration. But Mexico City artists’ involvement with signage is obviously not just a continuation of the modern art genealogy, but the embrace in general of the vernacular for their own conceptual purposes. Perhaps one of the best-known examples are the works of Francis Alÿs of the early 90s. In the case The Liar, the Copy of the Liar 1, Alÿs commissioned several rotulistas to make three enlarged copies of his own painting depicting two men wearing gray suits.

Francis Alÿs, The Liar, the Copy of The Liar- 1, 1991-94, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The interest in commercial signage among Mexican post-conceptual art of the 90s also goes beyond the handmade. For example, in 1998, artist Diego Toledo worked with commercial billboard companies to produce a number of enigmatic and compelling images. As he tells it, “there was anarchic and chaotic situation associated with this sector of advertising which grew out of proportion achieving a visual saturation where all kind of information would get mixed up.” He adds: “I wanted to generate images that would confound the viewer, containing a military-style slogan that would set a particular order or hierarchy.”

Diego Toledo, Te tenemos rodeado ( We’ve Got You Surrounded), billboard project in various locations in Mexico City with the support of FONCA, 1998

Other artists of later generations have done projects that help appreciate the value of the rótulo. In 2017, designer Cristina Paoli, along with various rotulistas organized an exhibition at the MUCA Roma museum titled Rótulos México where the master signage-makers also taught workshops of their craft.

Cristina Paoli in the exhibition “Rótulos México” at MUCA Roma, 2017

On a personal note, here I need to confess that in 1995, six years after having emigrated from Mexico to study in Chicago, I myself thought about these advertisements in a sentimental way and started producing banners that evoked completely imaginary and surreal businesses (a weird mixture of old Mexican advertisements and American freak show banners from the 1950s) evoking a past that had never existed.

Adelaido Cruzas, 1996, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago

But one can’t tell the long and complex history of Mexican artists and rótulos in a few paragraphs. What concerns me right now is the meaning of what happened in Delegación Cuauhtémoc.

The first and clear lesson that Mayor Cuevas should have learned by now is that politicians are terrible visual editors: considering that they have traditionally commissioned some of the worst public art in the world, they simply should have no business in determining what is aesthetically pleasing or culturally significant. Secondly, she has discovered the indirect psychological power of censorship: it only takes a prohibition of something in order to make it desirable, something that is described as cognitive balancing and which has been extensively studied over the decades.

Last but not least, and relatedly to the Borges passage, the violent erasure of these rótulos might have provoked a certain nostalgia for the old city. Neoliberal modernization brings with it homogenization and flattening of the visual identity of cities; that which is idiosyncratic is replaced by the mass-produced. Hegemonic dominance has also a material and visual form, and in the case of signage it is represented by corporate plastic logos of chain stores. The preservation of the hand-painted sign thus becomes a small form of resistance.

The question then becomes how the hand-painted signage can become a protected form of cultural heritage. Given that hand-painted signage is not officially considered a folk-art form per se there are no governmental mechanisms to protect it or support it like traditional Mexican crafts, for which there is FONART (Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de las Artesanías).

In reality, rotulistas connect with a very old pre-Columbian tradition separate from the other popular crafts: the profession of the tlacuilo. Tlacuilos, (in Nahuatl, “that who carves wood or stone”) did the job of scribes, artists, and writers. They painted codices and murals and carried out the representation of various business and natural records. They worked in markets and temples and basically freelanced in Aztec society. Tlacuilos were the ones who painted the codices that chronicled the events around the conquest.

Tlacuilo

Rotulistas— a contemporary commercial version of the tlacuilo— provided Mexico’s cities with a form of visual writing that gave the city a unique form of readability. Juan Carlos Mena put it best in describing the rótulo aesthetic: “these authors do not follow the norms of the academy, the conventions of the visual arts composition, and even less the latest fashions because they do not know them. Nonetheless they belong to a guild that form part of a tradition and as such their work has a style. Added to the ingenuity of the owners and their ideas of how to communicate the virtues of their products to the consumer, the result is almost always a hybrid, a combination of graphic ability and audacity.”

As this popular codification of the city is being redacted away and goes extinct in courtesy of the small-minded iconoclastic politicians and the vinyl digital banner printer, the hand-painted sign now needs to be rescued and preserved not just for its commercial but for its cultural meaning.

El narrador del Aleph no es Carlos Argentino. Carlos Argentino es el antagonista, un tonto despreciable y engreído.