Make Weirdness Alternative Again

Yearning for political normality in order to make weird art.

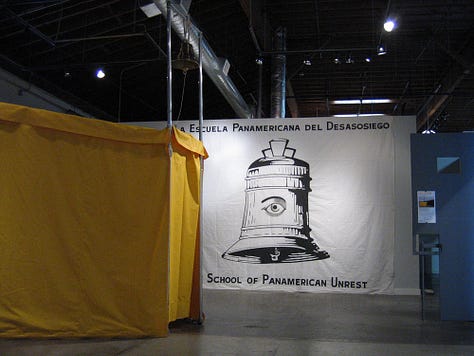

In 2006, when I drove through the Americas as part of The School of Panamerican Unrest, a project that sought to invite debate and reflection around the intersection of national identity and art making, a key aspect of that project was to develop a workshop in every city, primarily for artists. Each workshop led to a collective manifesto/proclamation of sorts (which became later a tradition at each workshop, and these became known as the Panamerican Addresses). From the first workshop emerged a common theme of rebelling against the homogenizing force of free markets and globalization to cultural practices, traditions, and identities.

The first address was produced in Vancouver, where participants wrote in one section:

Whereas we assert our right to ride naked in Vancouver and call it “art” and also to refuse calling it “art”; we assert the allure of our prosthesis; the natural and the supernatural;

In Portland, Oregon, the artists wanted to talk about their desire to assert their unique artistic identity while overcoming their own perceived liberal, passive isolationism, declaring: “We will not be absorbed into a mainstream that we disagree with, nor will we be separated into our own island of dissent […] We will plant parks on freeways; we will create art that moves past understanding and into action; we will burn the commodities of identity, we will teach cockroaches how to write”.

The speech also included this line:

“Whereas we recognize that Portlanders have bumper stickers saying “Keep Portland Weird”, acknowledging that this action is symptomatic of an isolationist tendency to retain our spirit as liberal but detaching ourselves from the rest of the nation.”

“Keep Portland Weird”, which became a popular slogan, was an offshoot of “Keep Austin Weird”, a spur-of-the-moment quip by Austin librarian Red Wassenich on radio while making a pledge to a local station. The phrase had such a great ring to it that Wassenich later created a website for it; it was embraced by local businesses and then it became viral. Per Wassenich’s recollections, (he passed away in 2020), “Most people likely think of the phrase as primarily a marketing phrase, which hadn’t crossed my mind when creating it. I certainly endorse the buy-local movement and I’m proud it helped, but my perspective comes from a street-level fondness for goofy, anachronistic, unserious, unmaterialistic bohemianism. Also from my inflated ego”. The slogan became a great message of the cultural moment of liberal American urban centers in the early aughts, explored by Joshua Long in his book “Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas”. As I observed in my interactions with artists in the west coast of Canada and the US over the course my Pan-American journey, this instinctive sentiment was the logical response by artists who wanted to protect alternativity from the cultural homogenization brought by what Richard Florida then coined as “the creative class” but which to them was a means to justify gentrification and corporatization of artistic practices. The “Keep ___ weird” motto, which spread to other cities, was a rallying cry to assert critical individuality, reject uniformity, and problematize any form of homogenization.

20 or so years later weirdness has made an appearance again, but not as a source of countercultural pride but as a line of attack against the idiosyncrasies of the far right. We all have seen how the Democratic party has restructured its political strategy, dispensing with “when they go low we go high” and instead using TikTok, memes, and sarcasm to upend Trump’s racist rhetoric against Kamala Harris ( the latest of it being #wheniturnedblack). But by far, the most effective strategy has been the deployment of the word “weird” by the newly minted Democratic vice-presidential pick, Tim Walz, to define JD Vance as well as Trump himself. As many commentators have observed, it has caught the Trump campaign flat-footed and scrambling for a good response.

The notion of weirdness already had made an appearance in the 2016 election. In a 2017 interview with Charlie Rose on 60 minutes, Steve Bannon described the Trump campaign as “The Island of Misfit Toys”, as a joke, but also an attempt to describe that those behind the MAGA movement see themselves as both outcasts but also as disenfranchised victims (the “forgotten man” in Trump’s inaugural “American Carnage speech” in 2017, which George W Bush described afterward as “some weird shit”) that are rising to take over. Then during the 2020 presidential campaign, Steve Schmidt, from the Lincoln Project, retorted to Trump’s Twitter attacks thus: “We are so much better at this than your team of crooks, wife beaters, degenerates, weirdos and losers.”

Both Bannon’s and Schmidt’s comments illustrate, in different ways, what the Republican party became under Trump. As conservative pollster Frank Luntz noted in a 2020 interview, “The Republicans of the 1950s, '60s and '70s were all jacket-and-tie, suit-and-tie Republicans, all properly raised, well-coiffed, suits that fit, and very quiet and respectful of the establishment. And it was the left who were the protesters. The left were the outspoken people, the left who were the angry ones. By 2016, it was the exact opposite.” In 2020, that contrast was so extreme that when Biden won the 2020 election, most of us — and the world— breathe a sigh of relief. The Washington Post put it best in 2021, welcoming the return to form: “There are days now when the administration is so radically normal that it’s actually kind of boring.”

As LP Hartley once wrote, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”. When we think back to the 1950s in the US, the heteronormativity, milquetoast whiteness, the rigid social structures of that world, the perfectly manicured lawn, the impeccable table set up by the housewife, the squeaky-clean car and forced smiles of the stereotypical middle-class nuclear family, strike those of us in the progressive left today as weird and at times even creepy. Back in 2012, in what now feels like a lifetime ago, the last Republican presidential candidate before Trump, Mitt Romney, displayed some of that stiff weirdness that had critics regarding him as a bit of a phony character from a 1950s sitcom (as he often spoke with quips and jokes that dated him to that period), later heightened by the revelation that he once tied his dog to the rooftop of his car for a 12-hour drive, and by his famous statement that in searching for female job applicants as Governor of Massachusetts he had “binders full of women”.

Of course, all those are quaint details now when contrasted with the deeds of a candidate criminally convicted on 34-counts. Invoking that mythical postwar world with the “Make America Great Again”, his slogan sentimentally and vaguely invokes that period of financial boom, yet conveniently glossing over, with those shiny pictures and idyllic portrayals of suburban life, the civil rights inequities, racism, the Cold War, the Korean war, and McCarthyism. So we can see that the yearning for the return of that world has thus merited the epithet of “weird”.

But the reason why I have not jumped into the “weird” bandwagon is not only that I don’t want to contribute to the already existing and unproductive viciousness and division in our political discourse, but also that I feel, to be honest, a bit (weirdly, shall we say) displaced, or rather, as the Mexican immigrant that I am, unwilling to be deported from my hard-earned weirdness.

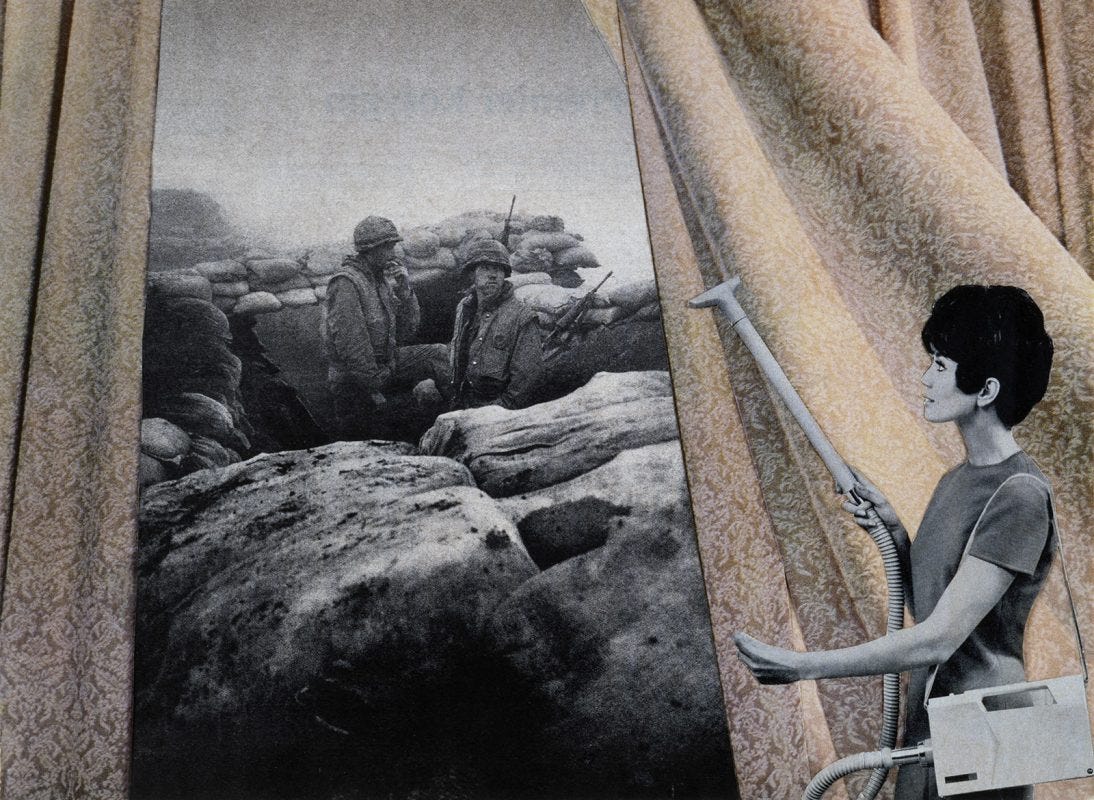

A key feature of artistic experimentation is its rebellion against normalcy—not for the sake to be different, but as an informed action and critique of the status quo. Contemporary artists who engage with challenging that status quo traditionally are attacked as weird, crazy, unstable, and even sociopathic; the romanticism around some of the most popular/ commercially consumed 20th century artists is partially built and exploited based on the perceived weirdness of their persona (Warhol’s wig, Dalí’s mustache, Kahlo’s eyebrows, etc.) more than, perhaps, on their work itself. Artists are accustomed to be called weird by people who live a typical bourgeois suburban or corporate life; in return artists see the unexamined and predictable existence of their suburban critics as ghastly and intolerable. In the 1990s, when I was in art school, photography and printmaking students were heavily influenced by the political photomontages of artists like Martha Rosler, who from the late 60s used images from home magazines to illustrate the American public’s utter middle class oblivious slumber and inability or unwillingness to understand or engage with serious issues like the Vietnam war. This mid-century representation of the perfect American suburban family was increasingly appropriated by artists to make satirical and/or sarcastic comments about race and class, to the point that, today in mainstream social media, we routinely see them used as “retro memes” to make sardonic comments around heteropatriarchy, abortion rights, and white supremacy.

What is revealed in this messy competition to ridicule the other with schoolyard sarcasm, is nothing but the underlying anxiety of the unpredictable.

The Portuguese theorist Boaventura de Sousa Santos once wrote, “We have the right to be equal whenever difference diminishes us; we have the right to be different whenever equality de-characterizes us”. The notion of weirdness was embraced by left-leaning underground culture as a way to assert its independence and celebrate its difference. Today, our so-called weirdness may be nothing other than our desire to be ourselves within our clan and with our internal logic; only seen from the outside may it strike to the observer as foreign and strange.

And while I fully subscribe to speak truth to power when it comes to specific political figures, we must not succumb to the temptation of otherizing large groups of people (this is was, in part, what likely doomed Hillary Clinton’s campaign when she referred to Trump’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables”). Instead, we need to pay closer attention to ourselves.

As sociologist David Berreby wrote in his book “Us and Them: The Science of Identity”: “When you understand your own kind-mindedness, then, you don’t just see yourself more clearly; you also see how ethnicities, nations, and all the other kinds can come to be. And you start to ask what it is about the mind that makes us see these human kinds, and believe in them, and fight about them.”

So, while I am more hopeful than I have been over the last year or so about the political future of the United States, and have savored the “weird” campaign, I do not see the benefit in piling on. Humor and critique aside, all that has to be overwhelmed with an affirmative vision for the future.

In the end, like many others all I want is a degree of political normality — to the extent that political normality can be so— so I can resume exercising my right to perform creative weirdness — and beautiful eccentricity.

Another great one, Pablo!... i have been feeling this exact sentence since "weird" became a MAGA descriptor: "So, while I am more hopeful than I have been over the last year or so about the political future of the United States, and have savored the “weird” campaign, I do not subscribe to that diminishing of difference."

The thing about weird is that, for me, it rhymes with a certain type of nerdiness, and ways of experiencing the world that let our imaginations stray from the status quo. I rely on this state for my own hope that change is possible ,and even sometimes likely, in spite of the ecological, social, political, and economic crises of our times. And mostly, because weirdness is about difference, it is also about how we encounter ideas and experiences that are unfamiliar, people who have life experience different from our own, it is, to me, at the core of what I would call multicultural democracy -- negotiating the spaces in between our weirdnesses.

This said, I think MAGA is another kind of weird entirely. And it did need to be named in a colloquial way that could be used as a short-hand. I'm just sad that weird is the moniker that got taken up... And also, words can have several meanings, just like more than one thing can be true simultaneously. So maybe I'll embrace this weird in an effort to support the complexity of weirdness, and the elasticity of my own definitions.

Buenísimo!!