Matchmaker, Matchmaker, Make Me Some Art

Idealized Guests and Reluctant Collaborators.

In 1966, Maurice Tuchman, then Senior Curator of Modern Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, proposed the creation of an Art and Technology program at his museum. He was able to amass a large budget to launch an initiative of unprecedented proportions: he reached out to 250 science and technology corporations, out of which 37 responded and 40 others formally accepted to participate. The massive 392-page final report to the museum’s board in 1971 shows the enormous ambition of the project (a useful summary of this report, created by the Daniel Langlois foundation, can be found here). Tuchman and curator Jane Livingston sought to pair the artists with the companies —a who-is-who list of the artists of the period, which included Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Irwin, James Turrell, Andy Warhol, James Lee Byars and Richard Serra (it is glaring to see that not a single artist was a woman nor POC, but that would not be the only nor the main problem, as I shall explain).

In her portion of her report, Livingston acknowledged how the relationship with technology had shifted from the earlier part of the 20th century, with artists now much more skeptical about the notion of scientific process (as their avant-garde predecessors) and instead more interested in producing works that would be more critical and outspoken about the encroachment of technology into people’s lives. This acknowledgment seems to be made a bit in retrospect, as, given the described state of mind of the invited artists it didn’t seem that not a lot was done to prepare the participating companies to productively engage with potential institutional critique agents.

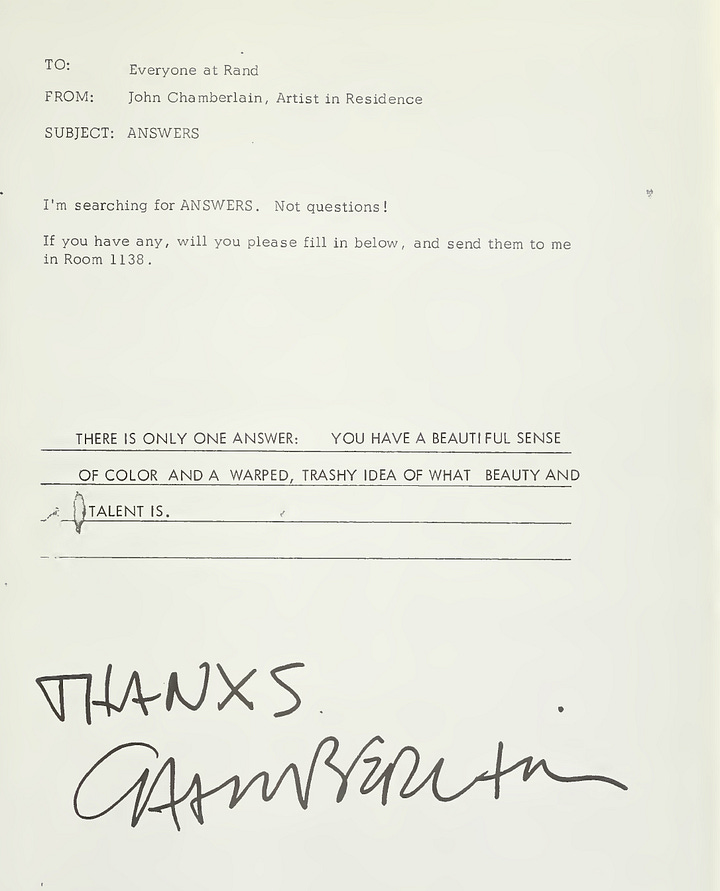

The initiative had mixed results at best; many would say that it failed miserably. As Joe Ferree, the current Art + Technology Lab Program Director at LACMA, recently (and candidly) wrote, “Collaborators stopped speaking to each other, artists walked off the project, technology partners balked at supporting creative ventures that lacked a specific outcome.” Some projects did not even go beyond initial correspondence between the artist and the corporation. Warhol’s capricious and hands-off working process (he developed a 3-D wall flower piece) showed caused great frustration (Livingston wrote “the entire installation operation was characterized by a sense of crisis, and there were moments where the piece seemed destined to ignominious failure”); Robert Irwin and James Turrell sought to collaborate with the aerospace engineering Garrett Corporation to study perceptual phenomena, but the collaboration became “non-goal oriented” according to Dr. Ed Wortz, Head of the Life Science’s Department at Garrett, and Turrell abruptly dropped out of the project after a number of experiments. John Chamberlain was paired with the RAND Corporation; as Maxwell Williams from KCET tells it, “His residency became fraught, with RAND employees bristling at Chamberlain's intrusion, and Chamberlain becoming frustrated with the RAND employees' intellectual pomposity in the face of his process.”

Oldenburg, who was paired with the WED Enterprises (the design branch of Disney Corporation), reportedly did not enjoy the constraints imposed on him; he did produce “Giant Ice Bag” (1969) in initial collaboration with WED but they eventually pulled out because of costs and staff time. One of the few important works that did emerge from this experiment was Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse, created in collaboration with engineers from Teledyne. Mud Muse is an aluminum-and-glass vat that holds thousands of pounds of mud made with bentonite, mixed to a specific viscosity that bubbles along a prerecorded soundtrack.

One outcome of the various artist residencies (although not something that was specifically planned at the outset) was a presentation of some art works at the 1970 Osaka World exposition, and then a show in 1971 at LACMA which was not well received by the critics. David Antin wrote a rather skeptical and ultimately dismissive critique at the time, first noting the disconnect between the exhibition and the idea of it being the product of a residency:

A piece by Robert Irwin was exhibited during the show in the Museum; it had no connection with anything that he had done in the course of his project with Garrett Industries. Question: what was it doing on the premises?

And then pointing out how the notion itself of technology had been stretched in order to accommodate the art:

The definition of technology as corporations is a Pop definition and fundamentally false. What it boils down to is the idea that technology is money, which has very little basis in fact, though it is true that the corporations cannot produce even the shoddy results that they do without chewing up vast quantities of money. But since they were unwilling to contribute more than trivial amounts of it to this show, even these pathetic expectations were unwarranted.

In fairness, and in spite of the critiques that LACMA’s Art and Technology initiative received at the time, it was an important experiment that pioneered the idea of having artists in residence outside of the art world and embracing the notion that an artist can be a catalyst for new ideas. It was also a key precedent for media art and the platforms that today support it, including the various organizations (e.g. MIT Media Lab, Eyebeam) hubs and partnerships (e.g. Rhizome/New Museum) that emerged in the 80s and 90s and continue to this day. Even LACMA’s own Art and Technology Lab, which I previously mentioned, is a direct descendant of those first experiments. Still, the question that interests me is: what really went wrong in that match-making process 56 years ago? The answer, seems to me, involves basic aspects of creative collaboration that are not particular to art and technology.

I share my perspective here with the caveat that I am a mere spectator half a century away from the events, and yet I dare to give it because, as someone who developed artist residencies in art museums for a decade, some of the dynamics I read in the report and other accounts of the initiative feel very familiar. The best way I can summarize my observations is by placing them in two buckets: one involves curatorial criteria and the other the psychology of exchange and collaboration.

The selection criteria of the artists might have been the first tripping point. It is interesting that the list did not include artists like Wolf Vostell or Nam June Paik who by the early 1960s were already doing major experiments with video and television; instead the curators reached out to artists who worked in more traditional mediums like sculpture. In addition, the selected artists included many who already were established at the time (Oldenbug, Rauschenberg, Chamberlain, Warhol, etc.) instead of emerging artists for whom this opportunity could have become more defining for their careers. Bringing a star into a collaborative environment like this is not a great idea.

The second hurdle was the process of brokering relationships, which involves educating each collaborator on the interests and needs of everyone involved. Industries that are external to the art world generally do not understand the artistic process; it is common for, say, an automaker to think of an artist as more of an illustrator or a “creative” who would work on an ad campaign for their products— a concept that is highly insulting to a contemporary artist. Conversely, artists can be just as instrumentalizing of organizations, seeing them as means to their own ends— in fact most projects became attempts by artists to use the companies as extensions of their studios, without much reflection on how this benefitted everyone’s needs.

The fact that most artists were seen as their collaborators as eccentric and unpredictable must have played a role in how the artists themselves felt: our motivations are directly related to how we feel valued and needed. In psychologist’s Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, (critiqued over the years but its overall ideas are still helpful) esteem and self-actualization play a very important role in inspiring individual motivation. In my reading of that residency program, I suspect that both artists and company employees might not have felt appreciated by people who worked in very different spheres of theirs; both encountered a party that they were not used to deal with in the past, and thus did not have an interaction script; looks like the relationships quickly became adversarial. Perhaps the employees might have seen the artists at times as insufferable clients, or the artists might have seen the employees as unhelpful studio assistants? Last but not least, artists in this particular project were caught between the great expectations that the curators had about them as catalysts for innovation and the likely puzzlement by the company employees who didn’t know how to fit them into their daily work routine and their meetings.

The missing and most important ingredient, it seems to me, was the honest broker or mediator. It appears that artists were parachuted into unfamiliar corporate structures without the companies knowing what to do with them, so inevitably a lot of miscommunications ensued. In my many museum years and in the unusual role I had of being both an artist and a senior staff at a museum I felt I could simultaneously speak the language of artistic process and institutional operations, mediating many complex discussions and addressing artistic, financial and legal concerns. This is extremely difficult work that involves learning how to listen carefully and being an advocate for both parties (a primitive version, I imagine, of being a hostage negotiator). From experience I can assure you that it would have taken an army of expert museum mediators to help broker the dialogue between each company and their resident artist. Had they only picked 6 (as opposed of 64) artists to work with the results could have been much more consequential and lasting.

It is interesting to me that Tuchman argued in his report that the project in general, and the exhibition in particular, helped fulfill an education mission. Ironically, the problem with that initiative might have been precisely that the museum as an educational institution was unable to use its purported expertise to mediate the relationships between artists and the companies they were left to work with.

As we enter the second quarter of the 21st century, artists are much more multidisciplinary than they used to be, and the same can be said of our modes of working in museums. While the LACMA experiment remains a cautionary tale, I also find its spirit inspiring and feel we can learn from it. So I would like to make a call to all art institutions out there: if you have not done so already, you should consider opening an R&D lab at your institution where artists are actively involved. If art institutions are to be experimental platforms for new ideas, you can attain the capacity to play that expert broker between artistic practice and other spheres of scientific, social and even political activity. The experiments undertaken might not always bring something new or surprising, but this is what lies at the very core of experimentation. We live in a siloed world where the withdrawal of art making into its own sphere only makes it more of an elitist commodity; we need to take it out into the world to help improve it, even if the interaction between these two worlds causes friction. Otherwise, paraphrasing Marguerite Duras: “as long as nothing happens between them, the memory is cursed with what hasn’t happened.”