I write these lines from the French Concession neighborhood in Shanghai, where I’ve been invited by the De Ying Foundation—a curatorial platform focused on socially engaged art, pedagogy, and curating—to give a series of lectures. This is my first visit to mainland China, and I arrived with a sense of eager anticipation, hoping to measure the layered mythologies, secondhand narratives, and outsider interpretations I had long carried against the reality on the ground—as much as a short stay would allow. As it turns out, Shanghai is a remarkably fitting entry point for someone like me. It is not only one of Asia’s cultural and economic capitals, nor merely the world’s busiest port city, home to a large international community (in 2018, there were approximately 200,000 foreign-born residents—a number that dropped to 72,000 following pandemic restrictions). What drew me in more deeply was its tangled, nostalgic colonial history—the kind of history I often find most compelling.

Nowhere is this more palpable than in the former French Concession, a semi-autonomous enclave that existed for nearly a century until World War II. Like other treaty ports, it operated under extraterritorial jurisdiction, with foreign powers exercising control outside the bounds of Chinese law. This layered legacy—of imposed modernities, shifting sovereignties, and ambivalent inheritances—is etched into the city’s fabric, and it became the backdrop for my encounter with Shanghai.

My first surprise in Shanghai was encountering a cityscape that so vividly evoked the neighborhoods of my childhood in Mexico City—despite being half a world away. Walking along Anting Road, I found myself reminded of Polanco and parts of Colonia del Valle. One particular corner instantly conjured the intersection of Avenida Nuevo León and Vicente Suárez, home to the beloved El Péndulo bookstore. A particular building made me feel like I was in the corner of Aguascalientes and Culiacán streets, around the corner of my grandmother’s old apartment in Condesa.

Hengshan Road, in particular, made me think of Paseo de la Reforma. The resemblance, as it turns out, is not accidental. Both boulevards were shaped during periods of French intervention: in Mexico, during the brief reign of Emperor Maximilian in the 1860s—originally named in honor of Empress Carlota before being renamed Reforma after the fall of the empire; and in Shanghai during the height of the French Concession in the 1920s, when what is now Hengshan Road was known as Avenue Pétain, later renamed after Mount Heng, one of China’s five sacred peaks. Both streets reflect attempts to “modernize” their respective cities through imported urban ideals—wide, tree-lined avenues framed by European-style architecture that sought to project aristocratic order and cosmopolitan sophistication.

The French planted London plane trees along both roads—trees known for their broad canopies, peeling bark, and pollen-laden seed balls. These yellowish tufts fill the sidewalks in spring and are an irritant to many residents. That small, persistent irritant struck me as an apt metaphor for the displaced and residual modernisms I kept encountering—imported forms that still cling to their environments, both shaping and subtly agitating them.

In contemporary China, this colonial architecture is neither celebrated nor condemned. Instead, it is selectively preserved, adapted to serve present-day narratives of urban development and national progress. A vivid example is the Rockbund Museum, a contemporary art space in the Huangpu district. Once a neglected area, the district has undergone extensive revitalization, and the museum now inhabits a 1932 Art Deco building that originally housed the Royal Asiatic Society—one of China’s first public museums. Its terrazzo staircase, elegantly restored by David Chipperfield Architects, transported me straight back to the buildings of Condesa and Roma, with their early modernist ambitions and layered histories.

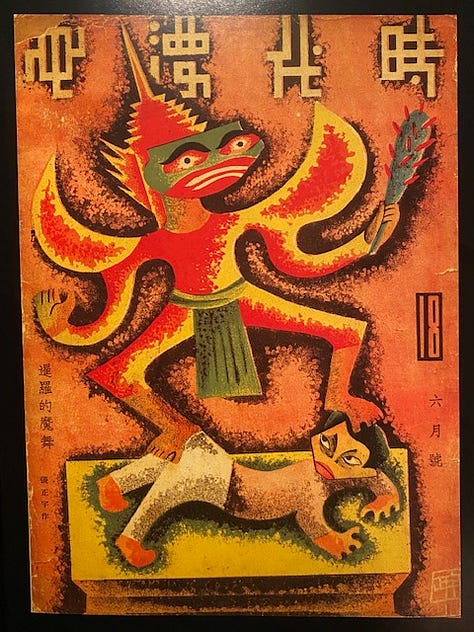

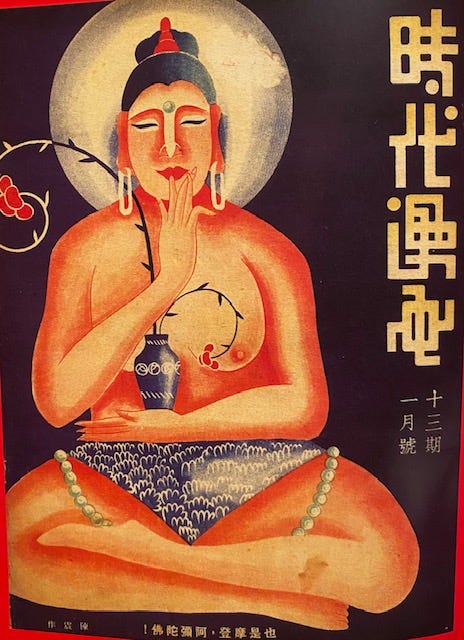

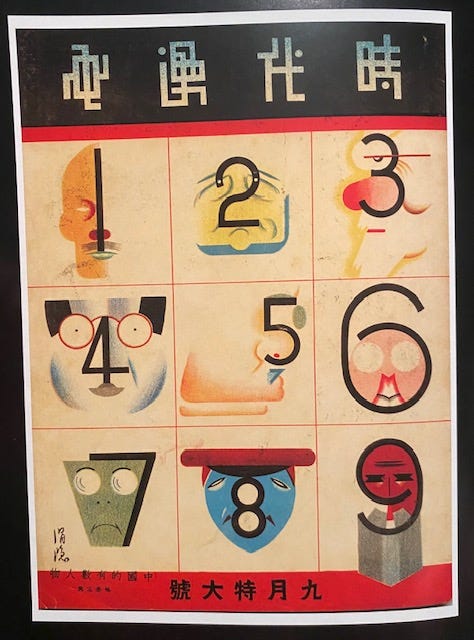

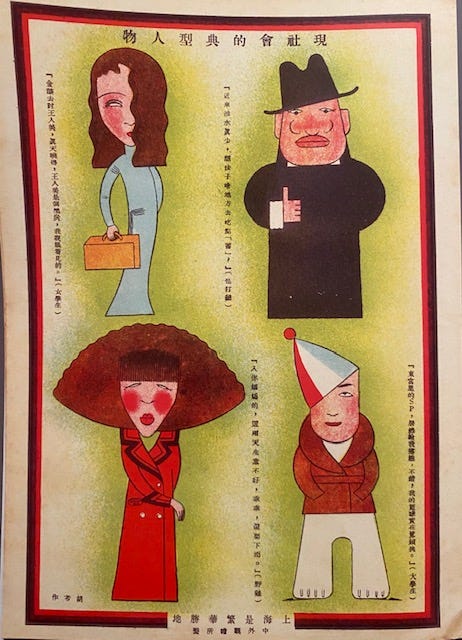

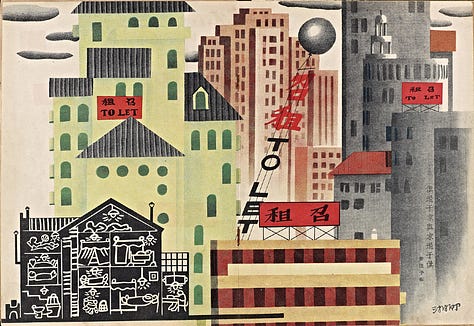

Another one of those moments of familiarity came when we visited the Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Centre, which shows posters and publications from the Maoist period of communist China, specially the period of the Cultural Revolution. Here I encountered for the first time the issues of Modern Sketch, a magazine published in Shanghai between 1934 and 1937, a period during which the art scene Shanghai was constructing its own version of modernity. The racy magazine was known for its cartooning and satirical depictions of culture and politics, and for its erotic drawings à la Playboy magazine. The publication came to an end with the Sino-Japanese war, after which the kind of cosmopolitan irony that the magazine promoted was no longer tenable, replaced later by anti-Japanese resistance themes and the social realist aesthetic that came with the Maoist period.

Once again, I experienced a Mexican flashback, not by the obvious connections between Mexican muralism and Chinese social realism, but by the amazing resemblance between some of the drawings of Modern Sketch and the illustrations of the Mexican Estridentismo of the 1920s, particularly Ramón Alva de la Canal. Both in China and in Mexico, local artists were dealing in a reactive way with European modernism, adapting Cubist-Futurist ideas in a woodcut graphic aesthetic that somewhat reconnected them with their respective vernacular traditions. As is often the case with artistic movements crafting their own responses to European avant-garde models, satire, irony, and even sarcasm become central tools in the construction of those alternative modernities, both stemmed from the impulse of embracing and yet rejecting influence, of criticizing the status quo but remaining nihilistic and non-committal to any specific position, an ambiguity that illustrates the discomfort of not belonging to anything in particular other than the state of doubt and social critique. This luxury of maintaining an ironic, irreverent stance was seen as a bourgeois privilege that was soon erased by Chinese communism. As for Mexico, even while the Estridentista manifesto argued for some form of locally-rooted avantgarde (ending with the cheer “¡Viva el mole de guajolote!”) its version of modernity was never sanctioned by the Mexican state, which instead favored the social-realist identitarian narratives of the Mexican muralism. In both cases, nationalist aesthetic reduced the possibilities of a highly individual or contrarian perspective, and in both cases we see different versions of attempted but ultimately unfinished modernist experiments.

I thought about these examples in the context of the 2008 Guangzhou Triennial, curated by Sarat Maharaj, Gao Shiming, and Johnson Chang under the title “Farewell to Post-colonialism” (to clarify, China was never colonized like India but did experience forms of semi-colonization such as the extraterritorial rights given by unequal treaties that resulted in regions like the French Concession).

The triennial sought to critically reassess dominant Western postcolonial frameworks, especially in their tendency to impose homogenizing readings on diverse local modernisms. This position would open the door to understanding publications like Modern Sketch not merely as derivative of European modernism, but as expressions of an eccentric, self-directed modernity—what one might even call, borrowing from Brazilian modernist discourse, an anthropophagic spirit that digests and reconfigures foreign influences into something distinctly local.

The most important legacy to me of that curatorial premise, which feel especially true in 2025, is that those old adversarial reading lenses of postcolonial theory are not very useful to capture the nuanced histories of local artistic experimentation and interconnectedness, as neither is the binary global/local. More interesting to me is what I can learn from the tension between the familiar and the unfamiliar, being in this place that so closely resembles the architecture of my childhood, yet containing a world that is so different. Which also made me think of the fact that the greatest irony is that when I am back in those places of my childhood in Mexico City is that I am never truly back: they all have changed, as have; the encounter is warm and welcome, but there is also sadness in it. So when I stand in Henshan Road I am also, and actually in a similar crossroads of the familiar and the unfamiliar, as when one sees a passerby that physically resembles someone who was very close to you once, but they are not them. It’s a melancholy encounter.

This is perhaps the kind of liminality that Edward Said once described in his memoir “Out of Place”: “I have never felt fully adjusted to any of the worlds I’ve lived in, and have felt at odds with all of them: at home abroad, and abroad at home.”

This is why perhaps, I always go back to irony and humor, another strategy of deterrence that helps face the threats and complexities of the world.

But in any case, humor, irony or sarcasm aside, the practice of living, as the art practice, is inevitably a constant exercise of finding the familiar in the uncanny and the uncanny in the familiar. This might be best understood in culinary terms, where unexpected flavors meet. It is true of the mole de guajolote, the figure of speech of the Estridentista slogan and one of the most complex dishes in Mexican cuisine, which contains 20 to 30 ingredients. In Shanghai, one dish that rivals such complexity is “Buddha Jumps over the wall”, (佛跳墙” Fó tiào qiáng) originally from Fujian province but common of Shanghai banquets, which takes 6 to 8 hours to prepare.

Finding comfort in incongruence is universal. As we say in Spanish, “aquí y en China”.

火鸡莫莱万岁!