Two years ago, Claire Bishop published an essay in Artforum titled “Information Overload,” addressing the growing prevalence of research-based art. Bishop has always had a sharp eye for contemporary art trends, and she often traces their historical roots while subjecting them to incisive critique—much like she did in her seminal 2006 essay on social practice, The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents. Her writing tends to function like an X-ray of my own artistic practice, which both fascinates and unnerves me; she often gives form to internal debates and diagnoses pitfalls that I—and many peers—grapple with daily. In the case of “Information Overload,” she examines how artists present research in their work, particularly how this can result in installations that flood viewers with more information than they could ever absorb in a single gallery visit. With her characteristic acerbic wit, she critiques this overload as a performative display of intellectual effort, wryly confessing, “Whenever I encounter one of these installations, I start to experience a feeling of mild panic: How much time is it going to take to wade through this?”

The essay made me think about a number of things: first, what motivates an artist to choose to show their research in the first place? Certainly, all artmaking is the result of some kind of research, but what are the motivations of making the research part of the work, if not the work itself? More specifically, how is the presentation of information a vehicle to challenging official narratives or making an issue visible versus a mere gimmick, an illustrative academic exercise, or a display of vanity (as if one were saying, “look on my research, ye Mighty, and despair!”)?

Secondly, and relatedly, why/how can /should the work be critically studied as art work in relation to how effective and sound its research process is? This is a question that I have previously discussed in relation to education, while contrasting the difference between art as representation/ pretend play versus art as direct action.

But the more important question for me, as artist and as someone who teaches social practice, concerns the research models that we as artists should pursue, whether we choose to make them visible or not, in our practice.

Whenever challenges arise in artistic practice, it's often valuable to look beyond our field (i.e. familiar art technique and theory) for insight. Lately, I’ve been considering how principles and tools from investigative journalism could be integrated into art education—particularly for students interested in socially engaged work. There’s much we can learn from journalistic methods such as interviewing sources, gathering data, and conducting archival research. These techniques not only deepen the rigor of an artistic process but can also enhance our ability to amplify marginalized voices. With this in mind, I’ve been exploring the idea of developing a course specifically for socially engaged artists focused on these interdisciplinary approaches.

The first part of such a course would be a bit of a historical exploration of the adventurous group that started this field, known as the muckrakers— who received their name from a 1906 speech by Teddy Roosevelt who spoke critically of those journalists who were hellbent in exposing wrongdoing. These included Upton Sinclair, who exposed the terrible conditions of the US meatpacking industry, Ida Tarbell, who explored the monopolistic practices of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, and Jacob Riis, who in How the Other Half Lives (1890) illustrated with photographs the tragedy of urban poverty in New York City. As historian Walter M. Brasch wrote in his book on the muckrakers (“Forerunners of Revolution”), they “were the conscience of the nation, exposing the ills of society and demanding change.”

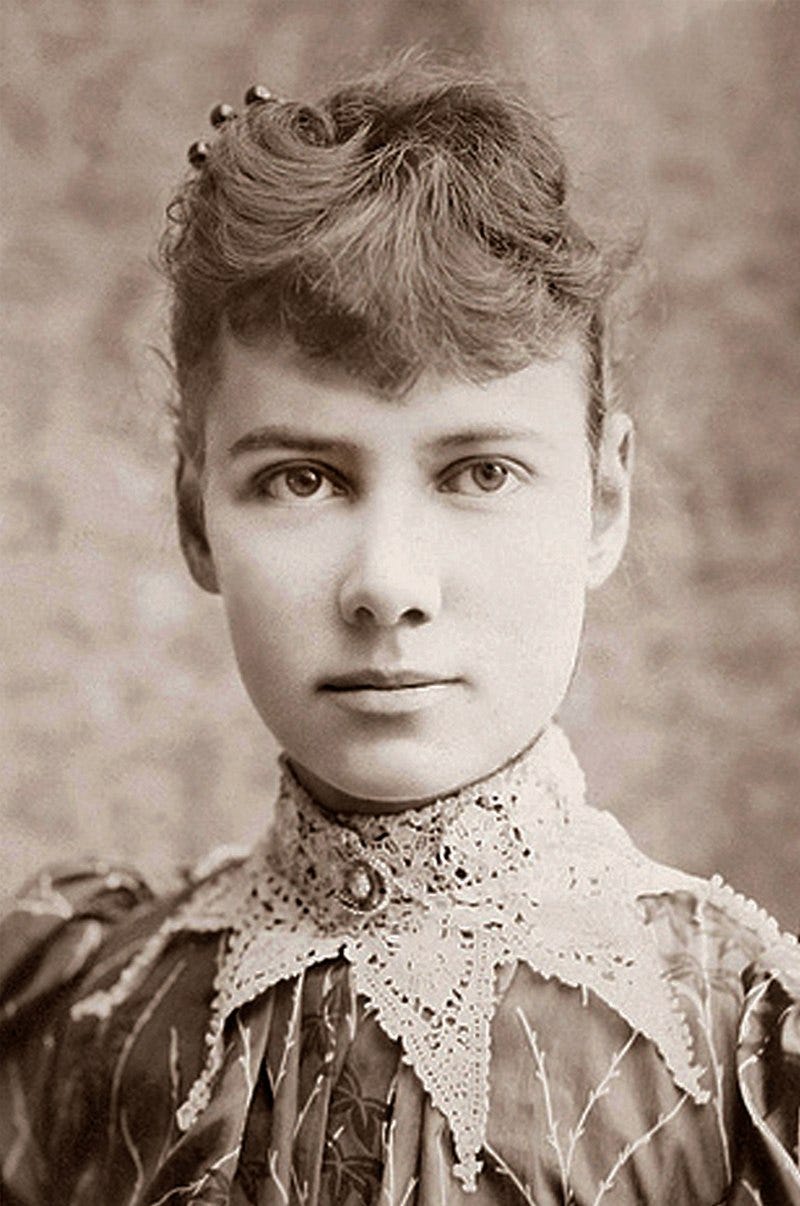

For my Mexican students, I would also make sure to dig deeper in studying a foundational figure of that group that particularly intrigues me: Nellie Bly (1864-1922). Born Elizabeth Jane Cochran near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she was a precocious writer and her first piece for the Pittsburgh Dispatch was a feminist article titled “The Girl Puzzle”, arguing that women did not need to marry. She was one of the first journalists to embed themselves in the worlds that they reported on, including a copper cable factory where she wrote about the terrible working conditions there. She was restless and I 1885, when she was 21, barely an emerging journalist, Bly traveled to Mexico to report on the country: “I was too impatient to work along the usual duties assigned to women on newspapers, so I conceived the idea of going away as a correspondent.” The result was a book titled “Six Months in Mexico.”

The Mexico that Bly encountered was an authoritarian dictatorship under the rule of Porfirio Díaz, who ruled from 1876 to 1911 (his rule led to the Mexican Revolution). During the Díaz regime, the country experienced economic modernization but at the expense of deep social inequality and the suppression of dissent: the opposition was jailed or exiled, political power was manipulated. In what might feel like a déjà vu for us in the US in 2025, Bly relates how there was a cult of personality of Díaz ("Everywhere are his portraits—his name spoken with forced reverence, as though any dissent would be a crime against the state."). Bly also wrote about poverty and censorship: “The rich lived in palaces, draped in silk and jewels, while the poor barely had rags to cover their bodies and tortillas to fill their bellies"; "A man had been imprisoned for publishing his honest thoughts. I asked questions. They said, 'Take care—do not speak so loudly. There are ears everywhere.'"; "It is a dangerous thing to be a journalist in Mexico. To speak against the government is to invite a prison cell or worse." Bly reportedly experienced a hostility and a threat of arrest which led her to leave the country. In a weird but interesting way, Bly can be read a bit like Alexis de Tocqueville is read in relation to the United States: a travelling foreigner who used their observations and experiences to make a social commentary of the societies they were temporarily immersed in.

The more I have learned about Bly the more I have admired and related to her sense of adventure and daring, and, mainly, how traveling was so central to her craft: Not long after the Mexico experience, at 23, she committed herself into a women’s lunatic asylum to report on its conditions, and then would travel again, this time to beat the fictional record of Jules Verne’s novel “Around the World in 80 Days” by actually doing it in 72 days and reporting it in a new book which is part travelogue and part memoir.

Which brings me back to the embedded nature of artistic practice. The artworld is structured in such a way that deep-embedded research becomes difficult: the demand for immediacy is such that long-term embedded research is difficult to achieve, and yet it is critical to produce meaningful works. This is primarily the reason why some of the best socially engaged works by artists are usually those made by artists who are intimately familiar with their locality, and are difficult to achieve with the usual biennial structure. Overcoming those constraints for an artist means to go it alone, which is often financially prohibitive, but it can be and is often achieved by those that are more determined and focused, finding ways to travel there often to research and slowly develop projects.

Another important question is: what can an embedded artist offer that a journalist cannot? Or more precisely, how can artistic practice bring forth something authentic and original without simply lapsing into amateur journalism? I first grappled with this question in 2004, when I began the project Conservatorio de Lenguas Muertas, which involved making wax cylinder phonographic recordings of last speakers of endangered languages.

Although the project was met with some skepticism from linguists—understandably so, as it was never intended to be a comprehensive or scientific archive—the public response was markedly different. But what the project offered was not data or documentation, but a visual and material representation of the immaterial process of linguistic extinction—something academic research, for all its rigor, is often ill-equipped to convey. In this sense, the artistic and the academic function as what Stephen Jay Gould famously called “non-overlapping magisteria”: distinct but complementary modes of understanding.

Returning to Claire Bishop’s critique of artistic research, some of the common pitfalls she identifies can be avoided by embracing the imperfect but complementary nature of artistic and visual approaches. Rather than mimicking scholarship or simply illustrating academic concepts, artists can promote non-discursive insights and visual thinking—modes of inquiry uniquely suited to revealing what traditional research often cannot. One particularly productive strategy, which aligns closely with investigative journalism, lies in the practice of situated knowledge: grounding artistic work in lived, material experiences that abstract scholarship is not equipped to address.

This doesn’t mean that an artist’s project must be rooted in personal subjectivity or autobiographical narrative. Rather, the challenge lies in striking a balance between objective representation and a grounded, human perspective. A compelling example of this tension between art and journalism is found in the work of Susan Meiselas, who once reflected: “The camera is an excuse to be someplace you otherwise don’t belong. It gives me both a point of connection and a point of separation.” Her approach exemplifies how an artist can remain critically engaged while personally present—without fully collapsing into either detachment or immersion.

I see a similar dynamic at work in Nellie Bly’s journalism. Her proto-embedded approach anticipates the spirit of artistic research—narrative-driven and performative, guided more by intuition and immersion than by rigid methodology. Bly’s distinctive voice turns investigation into a form of lived inquiry. To me, she embodies the spirit of a trailblazer, much like contemporary artists who forge new languages before their practices are codified, academicized, or reduced to prescriptive formulas. Both Bly’s work and artistic research share a commitment to discovery: a willingness to wade through uncertainty in the hope of illuminating complex problems.

This form of situated knowledge artist production is where we need to expand and/or improve forms of artistic research. It is not, once again, the academic exercise of compiling texts and illustrating them through video or immersive installations. And while the act of presenting materials as protest might be effective in the short term, ultimately the most relevant art is not mere journalism. As some of the artist I have mentioned show, and as Meiselas suggests, the key of a fruitful result from that embedded form of research is the balancing of closeness and distance with the subject, which can give a memorable visual form to social conscience.

This approach to the artistic practice, of course, is difficult to support with the current constraints of commodification and fashion imposed by the market, as well as by the demanded immediacy of art institutions (i.e. it is rare for an artist to be given a chance to research a topic for several years). But it is nonetheless essential. As Brasch concludes in his own book on the muckrakers, “even in its smallness, even when the forces of government, business, and the public arose to muzzle it, the voice of the muckraker has been heard as it sounded the call of a social revolution.”

“Rather than mimicking scholarship or simply illustrating academic concepts, artists can promote non-discursive insights and visual thinking—modes of inquiry uniquely suited to revealing what traditional research often cannot. One particularly productive strategy, which aligns closely with investigative journalism, lies in the practice of situated knowledge: grounding artistic work in lived, material experiences that abstract scholarship is not equipped to address.” Isn’t this what art has always done? Artists have always “researched” if we want to call it that, and then formed visual expressions of that research. Now artists and the museums that support seem to be compelled to explain, usually in excessive texts, what the viewer should be left to experience and understand on their own terms.