Mutual Aid

A conversation with Caroline Woolard on solidarity economy-based models of education.

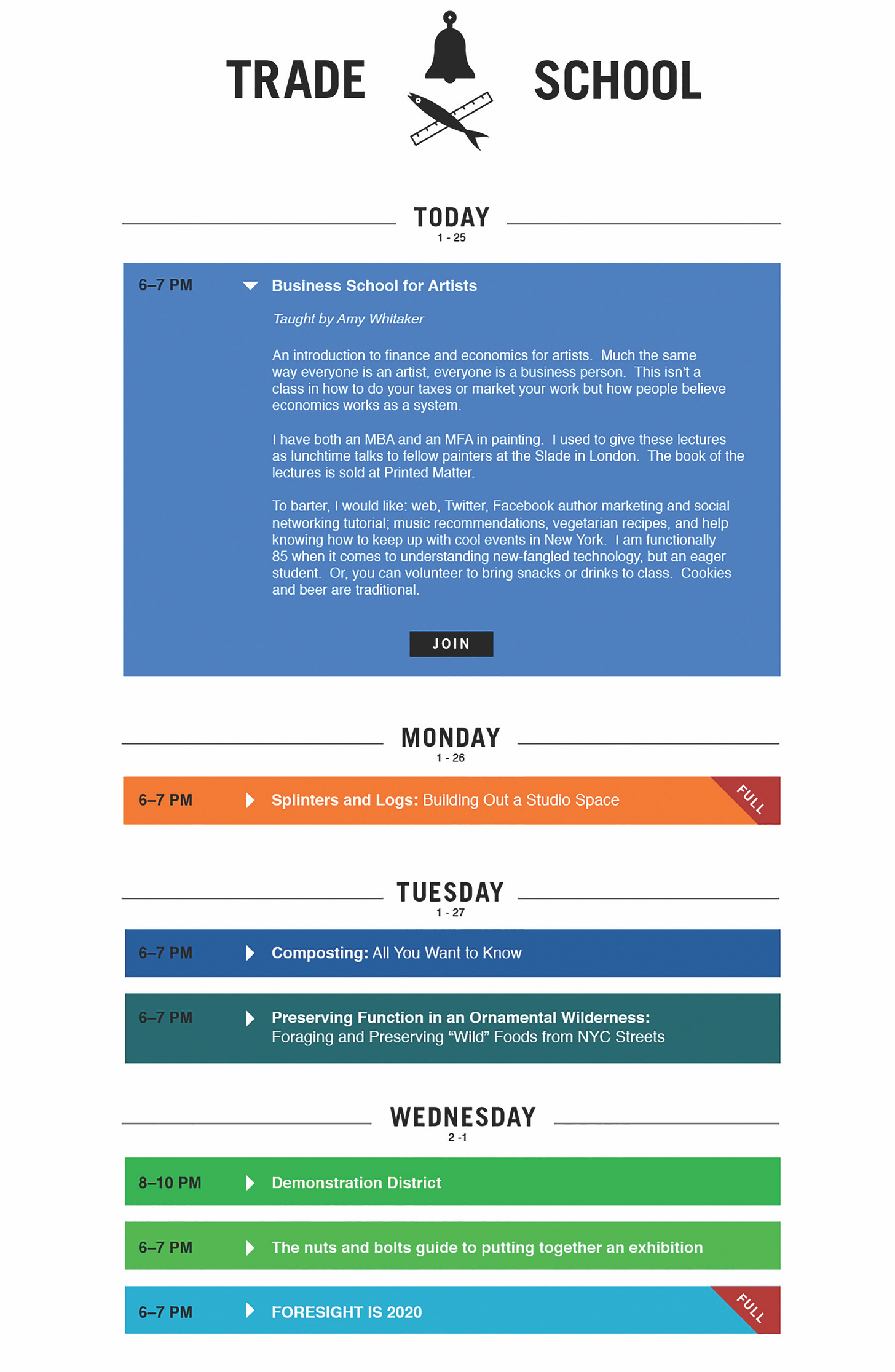

A session of Trade School (2009-2019). Image courtesy of Caroline Woolard.

In May of 2014, a Chilean performance artist named Francisco Tapia, a.k.a. Papas Fritas, managed to get access into the archive vault of the for-profit university Universidad del Mar in Chile, under the pretext of doing research for a project, then methodically extracted hundreds of tuition contracts and burned them all, thus effectively wiping out around $500 million dlls. of student debt. He showed the ashes of the debt documents in an exhibition, including an impassioned video announcing his action to the students and the world. “I burned them one by one. You don’t have to pay anything else; you are now free.” Papas Fritas, who did not have the chance to study in a university himself, said in the video: “ I am not a senator or a congressman, I am not a presidential candidate. I am a regular person like all of you. I give this to you with great love.”

While his action landed him in court, it nonetheless made international news and became symbolic of a movement that demanded free public higher education in Chile. A few weeks later, then Chilean president Michele Bachelet outlined a bill to reform the country’s education system— a process that took several years but which she eventually delivered on a few months before leaving office, and which included guaranteed free education and safeguards against predatory, for-profit universities.

Last week, when Joe Biden announced his three-part plan to provide relief for student borrowers in the United States, there was much debate back and forth about it in the twitter-verse, blogosphere and beyond. Regarding that intense debate we all had last week, quoting comedian Karl Valentin, “everything about it has been said, but it has not yet been said by everyone.”

But more can be said about how artists can help us envision alternative models of learning that are not dependent on traditional capitalist structures that are often prone to predatory schemes. And moreover, how can artists overcome traditional competitive scheme of the art market to instead find ways to support and learn from each other. And my go-to artist to talk about these topics is Caroline Woolard.

In 2008 I was in the process of organizing a conference titled Transpedagogy, based on a term I had proposed that referred to education-as-art projects— where the pedagogical component effectively becomes the heart of the work. It was in the research process for that conference that someone recommended that I speak with Caroline Woolard, then a 24-year old artist who had recently launched a barter-based project titled Trade School, an online platform that allowed people to propose and sign up for classes which are paid for using barter. As an artist that came of age during the Great Recession, the subject of economics has always been central in her work. Since the financial crisis of 2007-8, she has catalyzed barter communities, minted local currencies, founded an arts-policy think tank, and created sculptural interventions in office spaces.

Caroline has since then become a leading social practice artist who has led the thinking around solidarity economics, collaboration, barter, labor, and other forms of monetary and non-monetary exchange. She is now the Director of Research and Programs at Open Collective Foundation and co-organizer of http://art.coop with Nati Linares, Marina Lopez, and Sruti Suryanarayanan.

I wanted to get Caroline’s views of the future of education considering alternative economic models.

Trade School workshop schedule

PH:

Trade School was a project that lasted a decade, from 2009 until 2019. What did you learn from the experience and what aspects of it you feel could still be repurposed or used to apply for the existing business model of higher education?

Caroline Woolard:

I'm really interested in this model that a lot of people that I work with use, which is around resisting what's not working— such as exploitation —and [instead] building the worlds that we want.

But for grad school, I think it's not a choice between trade school or free public college. I think we always need peer-to-peer models. And yeah, trade school is very alive and well in my mind. The reasons I'm thinking about it lately is that where I work now, Open Collective. We have a tech platform and then we also have a non-profit called Open Collective Foundation. We're running what we call the Solidarity School. It's a way for groups and individuals to learn together, to build capacity around things like how to think about money. There's a group called the Money Health Collective and they do workshops with everyone which people reading this could attend.

Caroline Woolard

I'm just wondering, what are the ways in which peer-to-peer learning can be repurposed or even used by universities in ways that help maximize someone’s potential without leaving them alone to figure things out by themselves?

CW:

It's like [achieving] the balance of taking responsibility for yourself: knowing that you're the one in charge of your learning as a student or a person and not being alone. A lot of young talented people that I know, when they say to me “I want to go to grad school” I often think that there is no program for them because they are so smart and self-directed and have a very specific path of learning that they want to go on. I often think about the model that is offered at Goddard College or a lot of other schools that allow you to make your own plan like Bennington also has. This is a beautiful model, and I think this can be paired with peer-to-peer, and it could exist in an institution.

You construct your own learning path.

CW:

Yes. And what's good about it is you see the whole university as structured with leaders who hopefully are expert in these knowledge areas. And then you determine why. Like: what is the rationale? What is your long-term dream? What is a project you want to make or what are the things you need to learn for your own community wherever you're going home to? Maybe it's something that you want to share with your neighbor or your mom or your sister. Whatever the reason is, then you choose your courses and then you are in some cohorts based around a shared plan. That's the part that never happens that I'm interested in. And in regard to those models, I have always said, Why is there only your plan? Why isn't there a collective plan? Like what does it mean? What does it mean to be like my plan, my plan, my plan? If we don't have any clear shared direction, it's not going to go anywhere.

I also think that groups form around specific shared plans or shared goals, like a group being interested in [a particular] disciplinary area of the arts or interested in a certain like post-capitalist future regardless of our discipline, or we have a similar political leaning. I think that's where the peer-to-peer part can come in. But what's hard is that often people are not so skilled at finding their own agency and responsibility. They don't know what they want, and it takes a long time to figure that out. And then maybe if they do, they're [often] not so skilled at group facilitation or group work, and they don't know how to be accountable to their peers because they've never been taught that, because they've always been looking for a teacher or a boss or something. So shifting that around takes some work, but it can happen.

To follow up on that notion of collectivity: how have you negotiated yourself your own identity as an individual artist with this push for collectivity and the solidarity economy?

CW:

Yeah, it's so complicated. Often I say to people, if I'm giving a talk, “ I'm here at the podium because I did enough bad deeds, meaning elevate myself, make myself visible as an individual in order to get here”. So you shouldn't really listen to me fully unless it comes with that self-drive for the individual. There are other times when I have decided that there are moments when I want to be an individual which are usually around making discrete objects which I have not figured out how to make collectively. And I have very strong opinions about them. And I think I haven't yet figured out how to make a sculpture where you would be shaping the material together without speaking, because so much of collective work is verbal and discursive and language-based. I don't know how to collaborate physically yet, but I think I could learn a lot from musicians and from theater makers. [As to collective-based projects] right now, the way I'm thinking about it and the way I have done in the past is I make online platforms or advocacy networks with groups, and then I step forward when it's necessary because I have a relationship or I have the skill set that other people don't want to develop. But more and more with those platforms, I've been able to recede.

But you still you see yourself as an artist, correct?

CW:

Oh, yeah.

And you want this to be recognized as your practice?

CW:

Well, yeah, I think it's interesting. Right? On the one hand, let's say that the term can never change and therefore it's an old dead term. And I don't need to be related to it. And it has to do with the individual. It has to do with the birth of capitalism, get rid of it. And then the other way of thinking about it, like Claire Pentecost always encouraged me to do, is that I am part of changing the term art itself. And I feel like that's how our friendship, you and I, Pablo, is related. We are trying to change what the term means, and somehow also save the term so that it can be about collectivity.