Naming Opportunities

The ethics and aesthetics of donor recognition in museum buildings.

“John Waters in the john”, photo Erika Nizborski, courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art

Over the last week —apart from the opening of Documenta 15 and the animated discussion around it— a more pedestrian piece of news in the US art world was the story that the Cal State Long Beach Museum had been renamed the Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Gallery, accepted 150 paintings painted by the same donor into its permanent collection, and is currently displaying them in the gallery that bears the name of the aforementioned donor/artist. It appears that the gift was accepted by university officials during a gap period of museum leadership (and likely a time where there was no professional museum leader in charge to prevent this from happening). LA Times’ art critic Christopher Knight has rightfully written a scathing review of these atrocious works as well as a condemnation of the practice of selling out the soul of a museum to satisfy the ego of a rich donor.

The incident illustrates the vulnerability that some small university museums have within the university context, particularly when content and fundraising decisions are made by university leaders who know nothing about art or curatorial autonomy. A few years ago I led a staff retreat at a university museum suffering from a related dysfunction: the institution was understaffed and run by an ignorant and abusive leadership elsewhere in their campus constituted by failed artists who would force the museum to accept their mediocre works into its collection and organize exhibitions where, among other things, the very boss of the museum director would show his work. After gathering evidence of these practices from staff interviews, I submitted an unsolicited report for the university leadership suggesting that there should be a professional curatorial mechanism (e.g., an exhibitions committee, peer review, etc) to elevate the criteria and ethics of acquisitions and exhibitions— but the university told me that my report “was not accepted” since it had not been initially requested. I assume that this museum continues on the same path.

More importantly, the Cal State Long Beach museum case offers an opportunity to think about the raison d’etre of institution-naming and the opaque politics that govern it, in spite of how visible those institutional names usually are. A lot has been written about what museums should do when a donor who has named a museum wing or institution (e.g., the Sacklers) tarnishes their own family name through unethical or illegal practices. However, those scandalous examples aside, the opaque processes of donor-naming deserve much more critical scrutiny than what they currently receive. For starters, if we turn to how donor-naming has entered artistic consciousness over the past four decades or so, as we can learn something about this problem.

In the United States, we might be able to trace the incorporation of building inscriptions to the Early Classical and Roman Revival Style of the late 18th century— particularly the buildings designed shortly after the foundation of the Republic, which emulating that Roman tradition primarily contained words in Latin (such as in the Senate chamber of the capitol building: “annuit Coeptis”, “Novus Ordo Seclorum”, “E Pluribus Unum”, etc.)

As 19th century public institutions started being formed in the United States, we can see how many American philanthropists sought to inscribe their name onto the buildings of the institutions they founded (although there were important exceptions, such as Andrew Mellon who conceived and funded the idea of the National Gallery of Art but did not want the museum be named after him in order to attract other funders). Similarly, it became customary in many museums that the collections of wealthy donors would be held in galleries named after them.

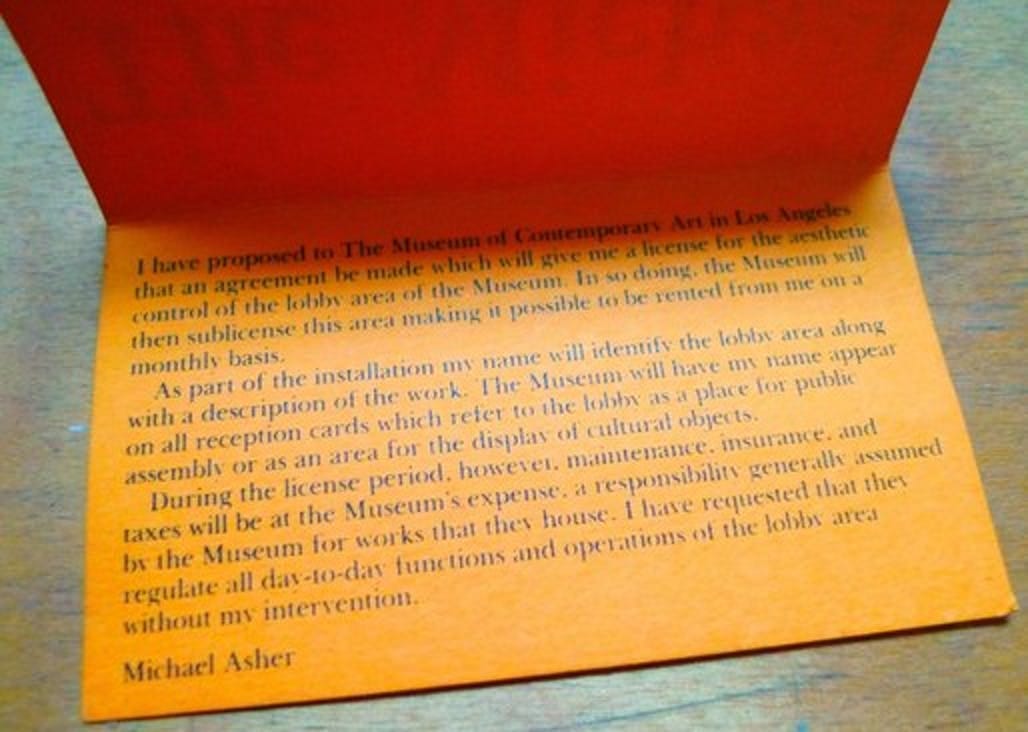

Michael Asher, The Michael Asher Lobby, LA MoCA, 1983 (photos by Orhan Ayyuce)

Attention to donor names in galleries became a centerpiece of- you guessed it- institutional critique artists. In 1983, Michael Asher made a work of LA MoCA titled “The Michael Asher Lobby”, consisting in having the name of the museum changed to his, giving him “a license for the aesthetic control of the lobby area of the museum.”

Cameron Rowland, MOCA 2015 Real Estate Acquisition, 2018

Artist Cameron Rowland had his go at the donor wall of that same museum a few years later, by adding a plaque that read “2015 MOCA REAL ESTATE ACQUISITION,” which refers to a $8.4 million gift from the Community Redevelopment Agency of Los Angeles (CRA). As writer Irene Sunwoo writes, “Among the other philanthropic contributors enumerated here, the CRA is one of the museum’s top benefactors. However, as a municipal agency—recently shuttered, it was founded in 1948 and for decades steered the redevelopment of “blighted” swaths of the city—it is an anomaly on the list of blue-chip supporters, which includes real estate tycoons, entertainment and banking executives, venture capitalists, and art collectors.”

Tania Bruguera and guests at the unveiling of her Turbine Hall commission at Tate Modern, 2018. Photo: © Tate Photography/Andrew Dunkley

One of the most important — and elegant— works in the category of naming is the 2018 piece by Tania Bruguera created for the Tate Modern as her Turbine Hall commission: permanently renaming a building after activist Natalie Bell. By honoring Bell, who is Head of Youth and Community programmes at Coin Street Community Builders, Bruguera made the Tate give a distinction that costed billionaire Len Blavatnik £50 million to obtain. Looking at a piece like this it is inevitable to reflect that it would be nearly impossible to achieve something like this in the context of American museums, which building naming’s constitute a major source of funding.

In a more humorous, but not less conceptually interesting approach, after filmmaker John Waters gave a generous donation of art to the Baltimore Museum and they wanted to name a wing of the museum after him in exchange, the self- proclaimed “Pope of Trash” requested the restrooms as the place that should bear his name forever— a perfect Duchampian decision. The John Waters Restrooms is fitting in more than one way, as it gives added meaning to the term “water closet”.

Other artists outside of the institutional critique discourse have also pushed in their own way against the egocentric push to forever enshrine one’s name in history, not necessarily by creating artworks but by building lasting art institutions without imprinting their name in them. In Mexico an example was the artist Francisco Toledo, who throughout his life created several museums and art institutions, aside from personally operating like a foundation, without ever demanding name recognition (the institutions he founded included the IAGO (institute of Graphic Arts of Oaxaca), the MACO (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Oaxaca), the Biblioteca Eduardo Mata (named after one of Mexico’s most important modern orchestra conductors), and along with other artists the Patronato Pro-Defensa y Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural de Oaxaca (a non-profit foundation to protect the architectural heritage of Oaxaca), among many others. Toledo’s projects were a marked contrast with artists of his and of the prior generation (such as Rufino Tamayo) who created foundations and museums in their name, usually holding their own works.

Which brings me to a small personal project.

Between 1998 and 2005 I worked at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum as Manager of Public Programs, most of which took place at the Peter B Lewis Auditorium. The auditorium has two main entrances—one from within the museum and another, usually used for the end of programs, that leads to a ramp toward 88th Street. That service entrance has a small transitional space, a hybrid between of an alcove, loading dock and emergency exit, that was always referred to as “The Garrett Lobby”. After several years of using this reference I learned that this was not a “named” space (i.e., by a trustee or donor) but merely an internal reference to a security guard who had manned the entrance for several decades— and the memory of his ubiquity in that location led to the informal naming of that lobby after him (I never got a chance to meet him, as he was gone after I started working there).

This kind of historic/circumstantial naming is not uncommon (for example, Martha’s Vineyard is not named after a famous or influential person, but after the name of the daughter of explorer Bartholomew Gosnold , in 1602). But in a sense, these circumstantial names feel even more relevant and important, since they are the result of a life that was dedicated to a particular place, instead of the certificate of a land purchase.

Today I would like to publicly propose a modest project to the Guggenheim: a small plaque that will officially name that small section of the museum as the Garrett Lobby, in recognition of that employee, as well as all the largely anonymous museum employees who pass its hallways, do the dedicated work of organizing exhibitions, hosting the public, and keeping the institution alive, most of which vanish into oblivion.

If accepted, I promise that the production of the plaque will be funded independently—gifted by an anonymous donor.

(with thanks to Tom Finkelpearl)