In 1972, a teenager named John Halpern walked into Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York and visited an exhibition of work by Joseph Beuys. When he first saw it, Halpern recalls, “I hated his work”. “I felt that Beuys was not socially relevant, making work that depended on the image of the heroic male, creating his own myths.” A few years later, in 1977, after attending SUNY Purchase, Halpern was doing his own experimental work, forming a collective titled Art Corporation of America Incorporated, and creating a performance titled “Bridging”. The project critiqued the attention that mass media gives to violence, and at some point it involved him and his collaborators climbing all of New York City’s bridges. The spectacle caught a lot of attention internationally. Shortly after, Halpern got a call from Feldman, saying that Beuys was very impressed by his work and wanted Halpern to come to work with him to Kassel to assist in his documenta project. Halpern was puzzled, but nonetheless, as he tells it, “I accepted Joseph’s invitation”. He flew to Kassel, where Beuys was presenting one of the iterations of his Free International University— in some ways the culmination of his ideas around pedagogy and social sculpture. “I was in a room for a hundred days with Beuys! – Halpern told me, as if in disbelief. “3000 people where coming in and out of the room every day”. “There”, he continues, “I understood his commitment to community and to the environment.” The experience was deeply impactful to him, and it was the beginning of a relationship that culminated in Halpern’s film “Transformer”, a “television-sculpture” portrayal of Beuys that was part of the German artist’s retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1988 (filmed at the museum and the only real-time record of the exhibition).

I had contacted Halpern to get his perspective around Beuys’ most famous declaration, “everyone is an artist”, which, like many other statements by famous artists has been widely misused and misinterpreted— yet this one phrase has particularly bothered me over my lifelong career as both an artist and educator, for reasons that I will explain further.

In 1973, Beuys articulated the rationale behind this phrase, which by that time had already become well known:

“Only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the deathline: to dismantle in order to build A SOCIAL ORGANISM AS A WORK OF ART. This most modern art discipline – Social Sculpture/Social Architecture – will only reach fruition when every living person becomes a creator, a sculptor, or architect of the social organism.”

It is important to note that Beuys’s phrase gained currency during the rise of the so-called “Me” generation— the baby boomers who were primarily focused on self-fulfillment. Beuys was clearly speaking about the universal need and ability to make within humans, a process by which one would be more fully integrated into social and natural environments. Instead, the statement began to be used as a way to praise selfishness. As Halpern noted, “In the 1970s when you say this, you are putting kerosene to the fire because that [statement] can be radically misunderstood and not what Joseph Beuys intended.”

Beuys conducting a workshop as part of the Free International University in documenta 6, 1977. © documenta Archiv / Joachim Scherzer

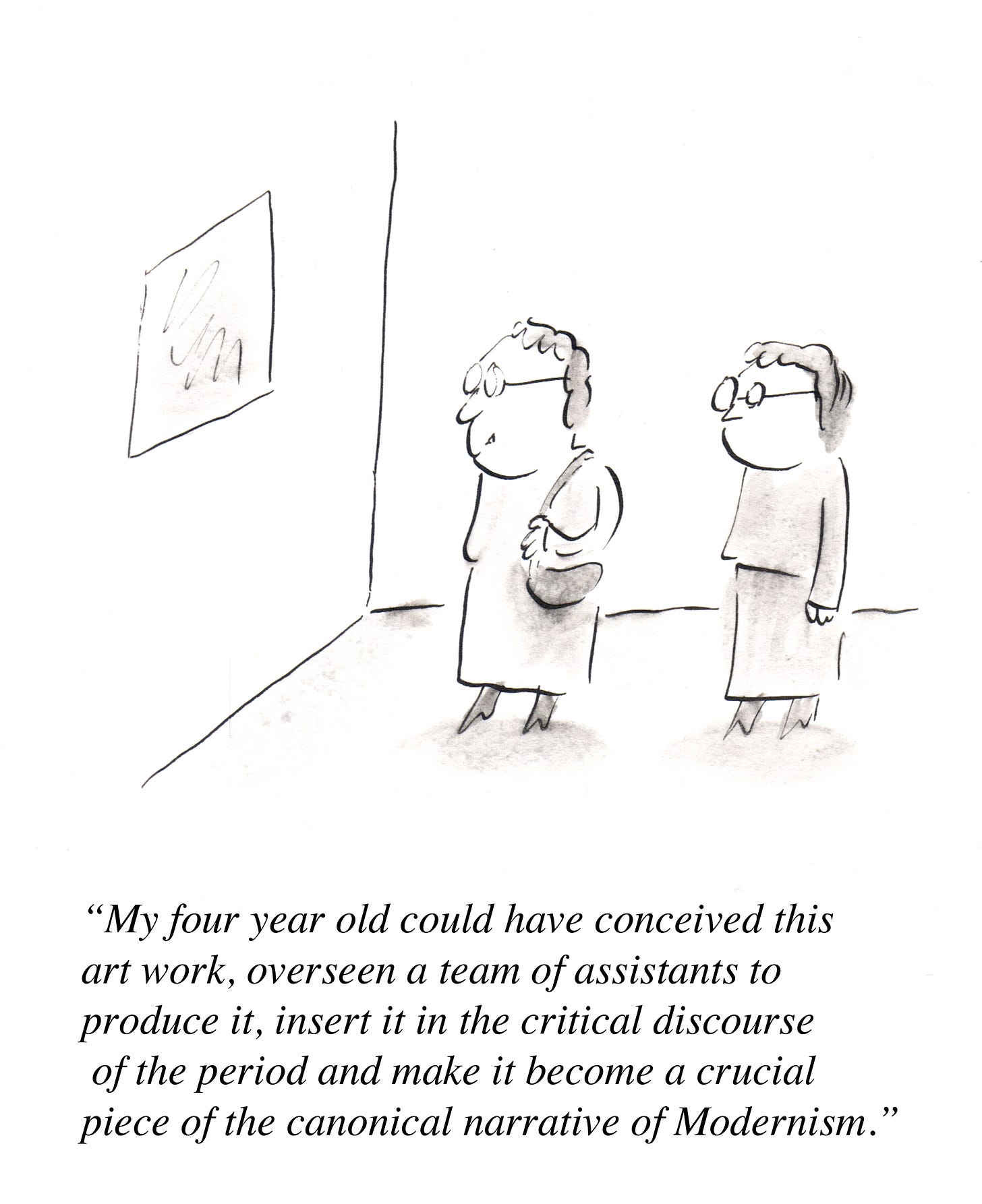

In addition, this intersected with the growing perception of contemporary art as an elitist practice accessible to only a class of individuals with a certain level of educational and financial access. So the well-meant intentions, by educators and others, to argue for the democratization of art as a form of expression that belongs to all, unintentionally extended to the implication that art is not a real profession since its ability to make it is ostensibly inherent in everyone anyway. No one can argue that everyone is a performing artist capable of playing the Chopin Études or Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto, but it would not be inspirational to add the small print of the real demands of the craft (that must be met by any professional artist) to the original statement. Further, the phrase seems to collectively bestow the title of artist as if it were an award, with all the glamour and romantic aura that surrounds it but without the actual accountability, critical exposure and professional challenges that come with being an artist. Lastly, the irony is that the emphasis that Beuys placed in the creation of his own messianic mythology makes the inclusiveness of his statement ring hollow: everyone may be an artist, but certainly no one else can be Joseph Beuys.

“We have the right to be equal whenever difference diminishes us; we have the right to be different whenever equality de-characterizes us” is an observation made by the Portuguese theorist Boaventura de Sousa Santos, who has contributed to the thinking around plural epistemologies. Over the decades, the usage of “everyone is an artist” has carried the opposite spirit of the statement in that it de-characterizes authentic human efforts of expression by implying that there is no useful set of criteria by which one should learn to communicate or make art, while it also diminishes the hard-earned knowledge and skills of those who have dedicated their lives to study and pursue rigor in their creative practice, by implying that their work should not be valued or appreciated more than the one casually done by the amateur or aficionado.

For decades in my museum life I experienced that very cognitive dissonance while attending curatorial meetings where art objects were intensely studied and scrutinized using the toughest standards, while after going into art education meetings where the standard was not the product but the quality of the process. It is no coincidence that I became part of the social practice generation of artists who firmly advocated that the process could, and should, be considered the product. And this is where one of the most fundamental, yet unresolved dilemmas lie in art making today: we saw it at its most explicit in the recent documenta 15, where the commitment to a social and collective process rebelled against the expectation of a more conventional exhibition experience of, shall we say, beautiful objects.

In conversation, Halpern recalled that during the documenta 6 discussions led by Beuys, where the subject of “everyone is an artist” came up, a woman asked: “how should I feel creative when I am peeling a potato in my kitchen?” According to Halpern, Beuys replied: “it is not the act of peeling the potato, but your connection with that experience that is of consequence.” Beuys’ response, however, cleverly evaded the commodity aspect of art making: the art practice is not just about having a private aesthetic experience, but about producing an artwork that later enters the public realm and the critical artistic discourse and then becomes enshrined in collective memory in museums and other forms of documentation.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation Performance: Sweep 7, Staten Island, 6:00 a.m. Roll Call, 1979–80. Citywide performance with 8,500 New York City sanitation workers. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

As I suggested, the greatest problem with the message of “everyone is an artist” might be the messenger himself. But the phrase is not meaningless. So, to get a better understanding of the true meaning of Beuys’ phrase, I think we need in fact to turn to other artists — for example one who incidentally was also represented and championed by Ronald Feldman and who in her work recognized the importance of pursuing equality without de-characterization: Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Ukeles is, in some ways, an artist who is diametrically opposed to Beuys in personality and philosophy, and yet someone who, in my view, was able to create a body of work that truly recognized the value of the individual without placing it in a contrived aesthetic or spiritual shrine. Ukeles’ focus was instead on labor and the recognition of that labor; and placing art making as yet another form of work not only humanizes the art practice but also communicates the fact that, like any other trade, it is an integrated form of knowledge, life and experience like any other— a much more contemporary and useful form of understanding, and valuing, that strange and mysterious thing that we call art.

(With thanks to Elaine Angelopoulos)

"Ukeles is, in some ways, an artist who is diametrically opposed to Beuys in character and philosophy, and yet someone who, in my view, was able to create a body of work that truly recognized the value of the individual without placing it in a contrived aesthetic or spiritual shrine." This wonderful sentence encapsulates my personal and professional journey. As to create against the prevailing grain of pervasive art apparatus tastes, values, and aesthetics is to journey in a deep dark forest with the light of a candle. The potential is full of wonder, possibilities, and plenty of pitfalls. Not for the faint of heart.

Analogous to this convo on democratization of art, I’d love to hear your thoughts on AI generated art: it’s “threat” to creative commercial jobs, it’s “aim” to heal public “creative constipation” so everyone can “poop rainbows” now, and where you seeing this affecting the institutional response some day. I’m and arts professor and commercial artist; this sums up how I feel so far: As a conceptual artist, [Ann Ridler] is well aware of AI’s shortcomings. “AI can’t handle concepts: collapsing moments in time, memory, thoughts, emotions – all of that is a real human skill, that makes a piece of art rather than something that visually looks pretty.” Here’s the Guardian article for reference: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/nov/12/when-ai-can-make-art-what-does-it-mean-for-creativity-dall-e-midjourney