Olfactory Dialectics

Learning through ambivalence and through our bodies.

Augusto Boal often remarked and emphasized in his writings that the body often knows things of which the mind is ignorant. To that I might add that such embodied knowledge often emerges most clearly under conditions of tension, discomfort, or emotional ambivalence. It is precisely when the body is unsettled—out of sync with its surroundings or in conflict with its habitual responses—that it begins to articulate what language or conscious thought has not yet grasped.

I thought about that two weeks ago, while staying in a large hotel somewhere in New England. The hotel was nothing to write home about, mainly one of those nondescript business chain hotels. Walking through a large carpeted ballroom that leads to its conference rooms, I realized I was having an overwhelming sense of longing and strong connection with that environment, which seemed rather incongruous as I had never been there before, and I am unlikely to ever return. It took me a few moments to realize that the reason I was having these feelings was because of the ambient smell in that lobby: I realized it was the exact same smell of the hotel Camino Real in Polanco, to which I have very strong memories and personal connections. So, there I was, in this city in New England, suddenly bonding with this nondescript corporate-looking lobby, almost on the verge of tears.

As an immigrant, smell often played a strong role in reconstructing memories and helping me reclaim fragments of my own self. The mixed smell of cigar and wine took me back to the times when I would visit the house of my uncle, the Mexican poet Eduardo Lizalde, who spent his life seemingly forever installed in his living room packed to the ceiling with books and vinyl records, playing loud opera and lecturing someone about Góngora, Verdi, or Mexican politics. Since that time, I have associated a certain scent with libraries.

Then there are the smells that conjure up complex states of mind of moments that carry strong, ambivalent feelings.

An instance for me in that regard involves the streets of Barcelona. In September of 1991, I flew for the first time to Europe, to be an exchange student at the Universitat de Barcelona. My very first encounter with the city included an assault of extreme feelings: on the one hand, the thrill of freedom— for the first time in my life I was traveling alone, and the farthest I had ever been from anyone I knew— combined with the deep trepidation of the unexpected ( I was a 20-year-old with the naivete of a 15-year-old). I had to stay in a Youth hostel while I figured out where I could rent a room for the semester. As I walked the streets of the city, the first and most enduring image in my memory is the one of the famous “Flor de Barcelona” square tile that lines most of the streets of the Eixample, designed in 1906 by Josep Puig i Cadafalch and which have become emblematic of the city; the streets also had a flowery smell which I associated with the tiles. I always surmised that the smell ( a citrus-y/pine smell mixed with some kind of ammonia) was probably the result of perfumed detergent used by Barcelona’s city cleaning services, which tend to do very frequent street-washing. Since that era, every time I visit Barcelona I can still distinguish those smells.

These embodied contradictions—the wave of longing triggered by a hotel lobby, or the bittersweet smell of a city street—are among the most meaningful experiences I’ve had. And yet, they are entirely un-sharable in their specificity. No one else can inhabit the exact emotional architecture of those moments, because they are tethered to the idiosyncrasies of my memory, identity, and personal history. This realization creates both a limit and a challenge: I cannot transmit my experience directly, but I can try to construct situations that might provoke similarly unresolved, sensorial conundrums in others. In my work, I seek not to illustrate what I felt, but to create conditions where others might feel something of their own—something contradictory, elusive, and embodied.

Countless artists have incorporated smell into their work (Sissel Tolaas, Oswaldo Macia, Anicka Yi, Olafur Eliasson) and a myriad of exhibitions have explored the subject in depth—too many, in fact, to meaningfully summarize here. Fewer of those artists, however, produce work that intentionally seeks to create dialectical tension—and one artist who exemplifies this with particular force is Cildo Meireles.

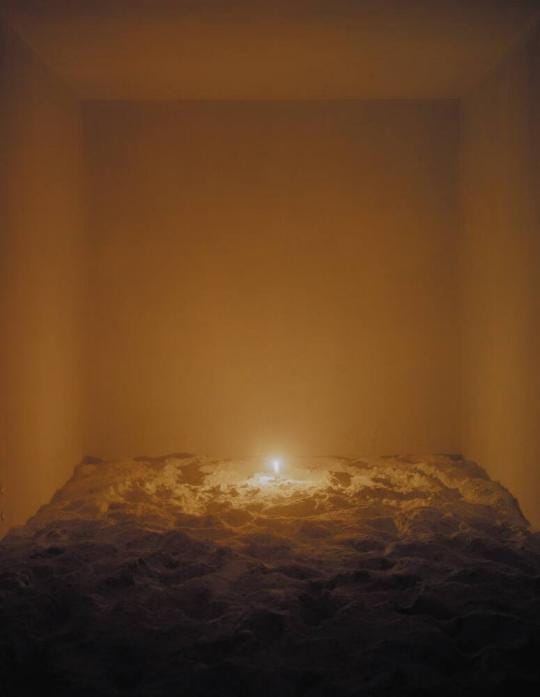

In his installation Ku Kka Ka Kka (1992/1999), Meireles juxtaposes the romanticized symbolism of roses with the stench of excrement, collapsing the boundary between beauty and revulsion. The piece corrupts the aesthetic ideal with the filth it emerges from, exposing the hidden violence or hypocrisy behind notions of purity, religion, or utopia. An earlier work, Volátil (1980–), stages a different kind of confrontation. Visitors enter a dimly lit, enclosed room whose floor is covered in soft talcum powder; they are asked to remove their shoes and walk barefoot across this seemingly serene, almost ethereal surface. But soon they detect a faint smell of gas. Turning a corner, they encounter a burning candle—a quiet but devastating contradiction between sensual comfort and implied catastrophe.

Meireles, working within the richly complex terrain of Brazilian conceptual art, employs these sensory juxtapositions—seduction and danger, beauty and abjection—to evoke the deeply contradictory states of contemporary life. His installations mirror how we carry on with mundane routines while scrolling past genocide, seek pleasure and distraction amid outrageous injustice. The critique, however, is not delivered through didacticism, but through the most visceral, immediate register available: the senses. In this way, his work offers not just commentary, but a form of embodied knowledge.

Cildo Meireles’ work offers a compelling model for navigating the longstanding tension between confrontational activist art and aesthetically seductive, formally resolved work that sidesteps conflict. Rather than seeing these as irreconcilable poles—agitational vs. seductive—Meireles embraces contradiction as a generative force. His installations often provoke simultaneous sensations of attraction and discomfort, pleasure and threat, thereby enacting the very contradictions of the political and social realities they critique. The viewer’s body becomes the site of this ambivalence: invited to participate, yet implicated; seduced by beauty, yet disturbed by its implications. In this way, Meireles does not resolve the contradiction between activist urgency and aesthetic subtlety by choosing sides—he embodies it. His work reminds us that political clarity and formal complexity are not mutually exclusive, and that the most incisive art often emerges from the friction between the two.

Sensorial-based work further addresses a deeper problem of communication that I have previously written about: that rational, discursive argument often fails in the face of ideological entrenchment. In political climates shaped by cult-like adherence to dogma or charismatic authority, intellectual appeals and factual corrections are rarely persuasive. What breaks through instead—if anything can—is affect: the destabilizing force of contradiction, the emotional dissonance of beauty laced with threat, the felt experience of something being not quite right. Meireles bypasses the cerebral and engages the whole body, compelling the viewer to feel the contradiction before they can name it. In this sense, his work is not just political—it is pedagogical, emotional, and sensorial, proposing that true political insight arises not from argument, but from a deep, often unspoken encounter with complexity.

Clarity does not always arise from simplification—it often emerges from dissonance. In the realm of social practice, we have sometimes shied away from emotional complexity in favor of legibility, consensus-building, or moral clarity. But what if, instead, we embraced contradiction not as a failure of message but as an honest reflection of lived experience? What if we recognized that confrontation and seduction are not opposing strategies but two necessary poles in the dialectic of persuasion?

Too often, contemporary art defaults to intellectual frameworks or minimalist aesthetics, under the assumption that spareness signals seriousness. Yet austerity rarely captures the full emotional spectrum of injustice or the layered experience of those most affected by it. Sensorial engagement—particularly through modalities like smell, sound, and touch—offers an alternative pathway: one that invites the viewer not only to understand but to feel, to be moved not by argument but by the body's own unease, recognition, or longing. If we are to reach those who cannot be reasoned with, then perhaps we must first learn how to disarm them—gently, unsettlingly—through the senses.

This fall, I decided to incorporate a signature scent into Librería Donceles—my itinerant Spanish-language used bookstore installation—because I believe that the sensorial experience of books extends far beyond the visual or tactile. The distinctive aroma of a library completes the embodied encounter, not in a confrontational way, but as a quiet gesture of recovery: an invitation to reinhabit a fragment of lost cultural memory. It is, in essence, a bittersweet dream of analogue knowledge—one that drifts gently through the air, perfumed with the scent of aged paper, soft mildew, tobacco, leather bindings, and ancient mothballs. If knowledge has a smell, perhaps it is this: dense with time, intimate, and slightly melancholic. I am certainly taking a page— pun intended— from my uncle Eduardo’s library.

This is where I find myself returning again and again—not to resolution, but to unresolved sensation. If art with a social consciousness is to remain vital, it must become more attuned to how things are felt, not only thought; how contradiction is lived in the body, not only debated in words. The path forward, I believe, lies in fostering spaces of sensorial ambiguity—where we as viewers are invited to linger in discomfort, to hold complexity, and perhaps, to remember something we didn’t know we had forgotten.

Cf. Marcel Proust and the madeleines... central thesis of A la recherche.

beautifully said