Public and Private Purpose

Keeping our artist statements to ourselves.

An urban legend has circulated for years about Diane Arbus’s Guggenheim Fellowship application (Arbus is top of mind right now due to the current survey of her work at the Park Armory in New York). According to that story, in the section of the grant where one is asked to state their statement of intent, she submitted a one-line proposal arguing that she deserved the grant “because I am Diane Arbus.”

While the story is apocryphal—her actual proposal was thoughtful and articulate—I think it continues to resonate because it captures the bureaucratic demand that artists translate their work into institutional language. It also reinforces the perception that granting procedures reward those who are eloquent or strategic over those whose strengths lie elsewhere. More importantly, the anecdote reflects a quiet rebellion among established artists—the belief that self-description should not be an obligation placed upon the artist, but a task left to the viewer.

I relate deeply to this resistance. Most of the time artists statements are superficial, rhetorical, written by someone who is trying to guess what the reader wants to hear from them while the reader tries to see through the rhetoric to understand who the author really is —usually with not much success. They are pieces that no one wants to write and no one wants to read but that we regard as crucial to key things like grant applications. I usually detect MFA language in those statements, kind of like the spiels one gets when one does studio visits in art schools. At times, the language tends to a Hallmark-version of art theory, sometimes it reads like a gallery press release; at its worst it is pedantic, overwrought and pretentious. Partially because of the feeling that it is a vacuous exercise of contrived professional courtship, I abhor having to write these statements.

The implicit common professional wisdom that statements of purpose are largely a rite of passage—something for the early stages of an artist’s development. Part of being established, in fact, often includes no longer needing to explain or justify one’s ideas or methods to others (as the Arbus urban legend illustrates). The expectation of reducing an entire practice into three Wikipedia-length paragraphs or a digestible soundbite can feel not only reductive, but vaguely insulting.

And yet, lately I have also realized that my abhorrence tends to mask a certain anxiety that paralyzes me: being able to summarize, in four or five paragraphs, what my true sense of purpose is. This is not to mean that I don’t feel I have a sense of purpose in life, but I struggle to commit it into words. I have been trying to examine this very anxiety over the past few days.

This paralysis probably has roots to which every artist can relate. One is the pressure (and the related reward and ease) to identify ourselves through negation— in other words, be ourselves by rebelling against something, that is easier than stating what we are for. Being proactive is always a way more vulnerable place to be at than being against something. Contemporary culture tends to romanticize nihilism as a mark of intellectual sophistication, while dismissing proactive or hopeful thinking as simplistic or naïve. Yet this posture of negation often conceals a deeper intellectual insecurity—a reluctance to engage with the risk and responsibility that come with constructive thought. This is a baggage that we continue dragging from modernism and of which we have not gotten ourselves entirely unburdened. And amidst this negation and excessive baggage, one can reach artistic maturity and realize that one still does not know what their artistic purpose is.

I have been reflecting on the fact that even young artists recognize that the statement of purpose is a mere rhetorical tool—a strategic performance—than a genuine expression of intent. I had a graduate student once tell me that he knew how to game the academic process, that is, he knew what to say and do in order to get an A. He did not think that his cynical approach meant that he would be only playing the game of performing knowledge instead of actually bothering to learn anything.

The obsession with declaring an artistic purpose as supporting something like market utility sometimes confuses purpose with product. I started thinking about this many years ago, when, as a grantee retreat for a major fellowship, I joined a professional development workshop sponsored by the granting foundation where the workshop leader took us through the process of creating a scrapbook where we would visualize things that we wanted to accomplish in our career: in her case, it was owning a house, having a fancy car, and being on the cover of Art in America, so she had cut and pasted magazine photos of a fancy home, a car and a photo of herself collaged on top of an Art in America cover (so far she had purchased the car). The “artist as brand” exercise repelled me, and eventually made me allergic to success coaching and motivational psychology that focus on overtly material outcomes. Instrumentalization of the self, anyone?

In trying to better understand this problem—and the broader question of what my purpose might be—I’ve recently been reading extensively on the subject. One challenge I’ve encountered is that the discourse around purpose is largely dominated by self-help psychology, hollow professional development rhetoric, and Christian life-coaching, most famously represented by Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Life (2002). The difficulty lies in the fact that writing about purpose almost inevitably risks falling into platitudes or sentimentality. Still, I believe that art careerists can take away at least one enduring insight, one that has been consistently emphasized by psychologists over the past century—from Viktor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning) to Victor Strecher (Life on Purpose): the idea that true purpose is not merely about personal fulfillment, but about striving toward something greater than ourselves—a self-transcendent purpose. This shift in perspective not only makes us better human beings, but also helps us shed much of the performative posturing that often plagues the pursuit of artistic success.

Another one of the overall commonalities that I have found among these various books and publications, from the high to the low brow, is that once you find your sense of purpose and/or your mission in life, you need to declare it publicly; shout it to the four winds, publish it like a manifesto, let the whole universe know. But here is a controversial idea: what if we were to keep our sense of purpose to ourselves?

I fully understand the need to make a goal public: it raises the public pressure to succeed ( I have undergone many such processes, from announcing marathon-like artworks that would bring me great shame it they failed and motivated me to complete them, to a journey a decade or so ago to lose weight, where making the goal public significantly raised the stakes).

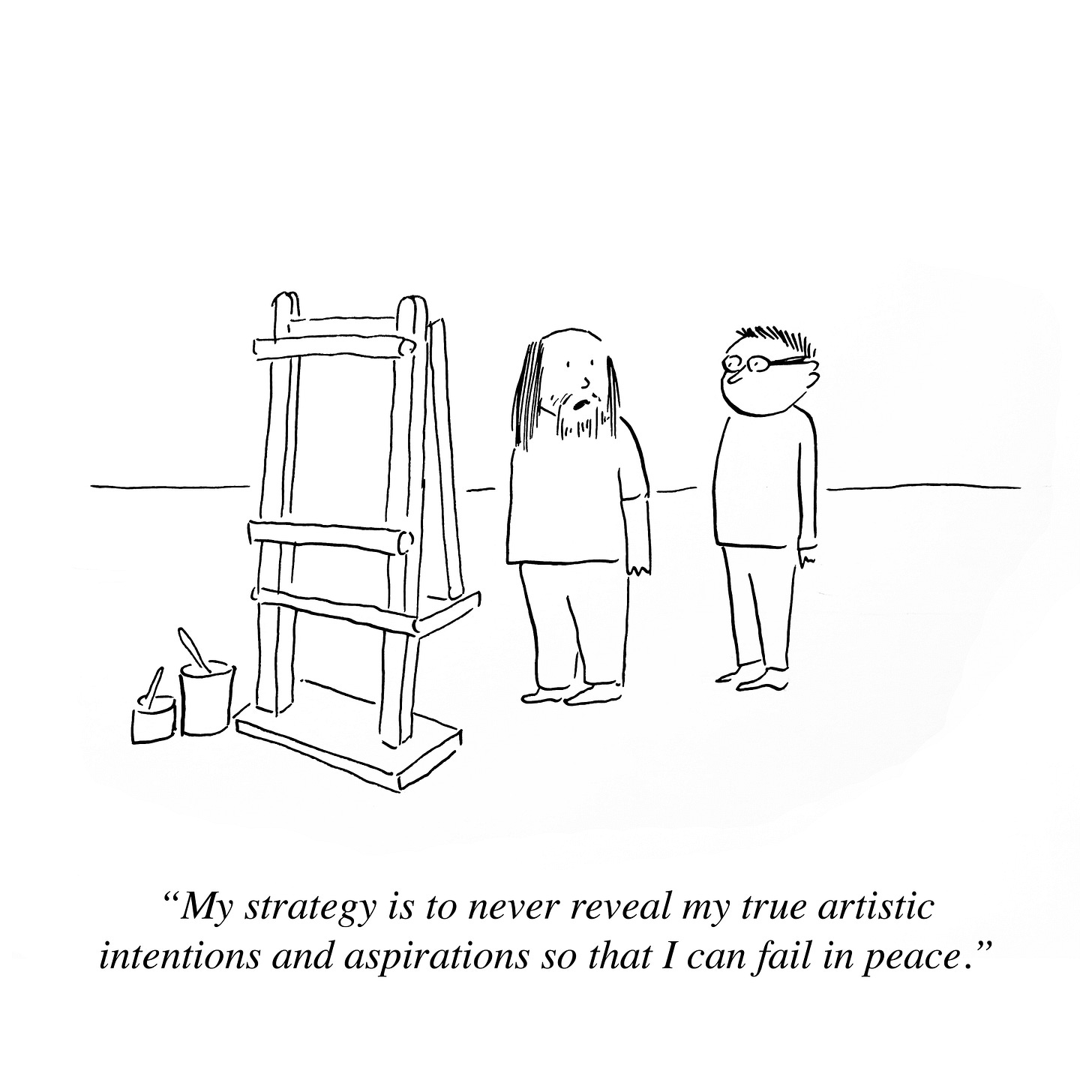

The problem, however is this: in a culture obsessed with self-disclosure, articulating one’s purpose has become an act of public branding rather than private reckoning. But there is a quiet integrity in cultivating a sense of purpose that remains unspoken—a compass that guides without needing to be announced. Paradoxically, this discretion can protect us from the dissonance of performing commitments we have not yet fully embodied. Put in the terms of the Artoon above, if you fail in your goals without no one knowing, then you are not really facing the agony of failure.

In addition, private statements of purpose are not for beginners. The danger is that being honest with oneself requires practice. And further: they also present a challenge for those of us who are more experienced, as we might not entirely know how be honest with ourselves, nor might we have the right mechanisms to keep ourselves on track. So here is a brief thought about that:

When I wrote my first book, The Pablo Helguera Manual of Contemporary Art Style, which was a satirical social etiquette manual for the art world, I studied the social etiquette manual of Manuel Antonio Carreño, a Venezuelan diplomat and author of the Manual de Urbanidad y Buenas Maneras, a 19th century social etiquette book that is still widely used as reference in Latin America. The book is of course old fashioned and I emulated the rigid structure of its rules for humorous effect. The book has a somewhat perplexing section in the first chapter, titled “the moral duties of man”, where the author writes the following:

Urbanity should not be regarded as a vain system of formulas and conventional practices, but as the expression of the respect we owe to ourselves and to others. Even when we are alone, we should behave as if in the presence of others, for personal dignity must never be abandoned.

Carreño focuses mostly on how we must behave with others, but argues that in order to our behavior transcend its performative nature we need to assume that same commitment and set of values in our private life. In other words, I need to place equal importance on how I perform myself to myself — a concept that might have suprised even Erving Goffman himself, who in his Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life focused on how we perform to others (but does not really talk about how we perform to ourselves).

When I think of the artists whose work most admire, I do think of how their self feels so authentic. I feel I can’t ever prove the following, but in any case: I feel certain that there is a perceptible difference between art that emanates from an artist’s inner convictions and worldview, and art that merely performs the gestures of meaning without living them. While interpretation is always subjective, we often sense—almost intuitively—when a work carries the weight of real experience, curiosity, and struggle, versus when it is a hollow imitation crafted for approval, trend, or opportunism. Authenticity in art reveals itself not by style or medium, but by the coherence between the artist’s questions and their way of working. Charlatanism, by contrast, tends to overstate, overpolish, or borrow sincerity in an attempt to simulate depth.

Now, going back to our dilemma: while a private sense of purpose preserves the freedom to evolve, it can lack the structural and emotional support that public commitment brings.

The challenge might be to find a space between isolation and exhibition—where purpose is shared not as a performance, but as an invitation to grow alongside others. I have detected this in the support systems that I have seen artists often have- whether it is their family, significant others, a community of loyal supporters and friends, and more. Within those inner circles the artist can be freer to share and find support toward their sense of purpose.

Last but not least, it is important to emphasize that a private sense of purpose does not enter into conflict with what I believe is the ultimate aim of most artists: a self-transcending purpose, which is what psychologists have argued for nearly a century: ultimately, we want to be remembered as someone who contributed to something larger than ourselves.

So, with that in mind, my recommendation is that you tell no one that you read this text, that you keep it to yourself, and that you quietly consider your own purpose. Feel free to tell only your inner circle, or not. Mostly, make sure that you tell it to yourself. I will be right there with you, in the solidarity of collective solitude. We might then hopefully achieve self-transcendence —even if we are not Diane Arbus.

Absolutely right. Thanks for your insights about art.

Beautifully written and filled with purpose!