Reading Assignments

Books that artist study, reference, and base works on.

Hope Ginsburg, M.O. Turtlegrass Meadow (Work in progress). Still from six-channel video and platform for public programming. Artist credit: Meditation Ocean Constellation

In Umberto Eco’s famous novel The Name of the Rose, which revolves around the investigation of a series of murders of monks in a Benedictine monastery in Northern Italy (whose deaths are caused, it is later learned, by having read a forbidden book), the Sherlock Holmes-like character and the hero of the novel, Friar William of Baskerville, says at one point: “books are not made to be believed, but to be subjected to inquiry. When we consider a book, we mustn't ask ourselves what it says but what it means.”

William of Baskerville’s statement, which we can construe to say that knowledge must be absorbed critically by the independent mind to assess its value and its use instead of accepting it as dogmatic truth, shows a humanist, pre-Renaissance mind in a world that is still dominated by medieval darkness. It also points, in my mind, to the inquisitive relationship that artists have with books, for reasons that I will elaborate further on.

Over the last two weeks I have been thinking more than usual about books, for two reasons: first because I am embarking to reopen my Spanish-language used bookstore (this time in Los Angeles) and because I am in the final stages of arranging the syllabi for the classes I will be teaching this fall, all of which, of course, include a bibliography. And for this reason I have been reflecting on how artists use books as theoretical reference, springboards to critical engagement, and even enigmas to be solved.

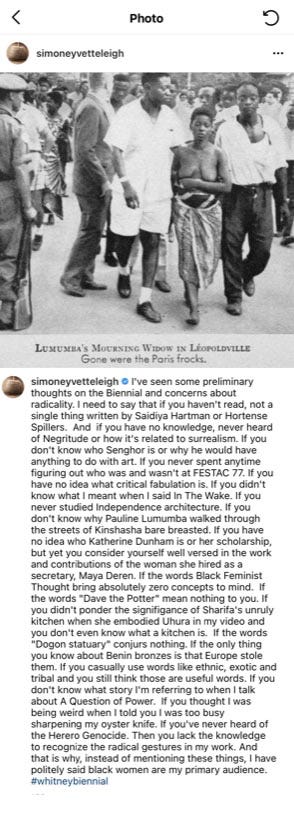

Back in May of 2019, Simone Leigh published an extensive Instagram post about the Whitney Biennial of that year (where her work was included) and the criticisms that exhibition received regarding it lacking radicality:

“I’ve seen some preliminary thoughts on the Biennial and concerns about radicality. I have to say that if you haven’t read a single word of Saidiya Hartman or Hortense Spillers. And if you have no knowledge of Negritude or how it’s related to surrealism. If you don’t know who Senghor is, why would have anything to do with art? (…) if you have no idea what critical fabulation is (…) then you lack the knowledge to recognize the radical gestures in my work. And that is why, instead of mentioning these things, I have politely said black women are my primary audience.”

I asked Leigh whether there was a particular book she felt would be of importance for viewers to understand the context of her work. Her response: Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America.

In her post, Leigh was responding to an attitude that I am unfortunately too familiar with, both in my own practice and over the years as an educator: that is, the common perception that meaningful art has to be merely a gratifying sensorial experience that is inherently communicative and self-explanatory, not a proposal for an intellectual engagement, and just as one can’t expect to understand a foreign language without ever studying it, the same applies to contemporary art. But among all the important references that Leigh mentions, it is the work of scholars and writers that I want to focus on here. The books of Saidiya Hartman (both Scenes of Subjection as well as many other of her works) have certainly played a central role in the thinking and debates among many Black artists today, and as Leigh notes it is hard to help an average viewer make sense of a work without understanding those references. It is also an example of how in today’s era of hyper-contextuality, artworks require the willingness and dedication of a viewer to draw meaning from them, and this should include educating oneself about the references that the artwork is making. I believe that for those interested in understanding socially engaged art, for instance, it is of key importance to read Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and, for those interested in understanding Latin American art of the last 50 years, Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America.

A year ago or so I invited my friends to contribute to an open, evolving and crowdsourced Artist Research Bibliography Database, to share books that they consider interesting and/or that they have assigned as readings to their students. The subjects range from philosophy to psychology and optics.

From experience I can say that there are two salient aspects regarding the relationship between artists and books which I believe are obvious to some of us but are not so to many.

The first is that artistic research is an omnivorous practice, definitely not limited to art-related subjects. By necessity we of course pay a great deal of attention to art history, art technique and theory, but each individual artist in their research eventually gravitates to subjects that might have nothing to do with art- either because they research a subject of interest, a historical event, or an obscure subject matter.

A primary model of artistic research of Hope Ginsburg, an interdisciplinary artist based in Virginia, for whom learning and absorbing information from other fields is central to her practice. “I'd go so far as to say that learning experientially with others is my medium.” She told me recently.

Ginsburg creates a bibliography of sorts for every project, following “total belief in following the breadcrumbs of curiosity where they lead.”

Ginsburg continues: “For me, these paths go far afield–and underwater. My bookshelf is organized project-by-project, with some books jumping around. Donna Haraway's "Staying with the Trouble" has leapt a few times, as has Adrienne Marie Brown's "Emergent Strategy," "Ecology, Ethics, and Interdependence: The Dalai Lama in Conversation with Leading Thinkers on Climate Change," and Roy Scranton's, "Learning to Die in the Anthropocene."

Ginsburg’s most recent work is Meditation Ocean, one for which she has assembled a vast reading list. “Here are some of the most dog-eared books: "Wild Blue Media" by Melody Jue, "Bodies of Water" by Astrida Niemanis, "Undrowned" by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, and most recently (an oldie but goodie) "The Spell of the Sensuous" by David Abram.” [as well as] "The Nutmeg's Curse" by Amitav Ghosh. For the embodiment vector in the work, I want to name "The Body Keeps the Score" by Bessel van der Kolk, and "My Grandmother's Hands" by Resmaa Menakem.” (The whole project’s reference library is listed on the project’s webpage).

The second thing to keep in mind about artists and books is to consider how artistic research is different to scientific research. The outcome of research (ostensibly a body of work instead of an academic paper) may be informed from that is learned but the engagement with the materials operates at many different levels, usually making an interpretation of facts from a critical social, political, or human perspective.

An artist who is both an avid reader as well as an expert at exploring, rescuing, and presenting history through the artistic lens, almost through an almost alchemical process, is Josiah McElheny. McElheny is known for his exquisite work with glass blowing and assemblages of glass and mirrored glassed objects, always showing, as Sabine Russ once wrote, “passion for modernity’s early days, its promises, its failures, and its forgotten stories.”

Specifically on the subject of books, McElheny devoted an entire project of his to the work of German author Paul Scheerbart, which included publishing two books on Sheerbart. The first was a response, with collaborators, to an obscure short story written by German author Paul Scheerbart titled The Light Club of Batavia: A Ladies' Novelette, about a club dedicated to building a spa for bathing in light at the bottom of an abandoned mineshaft. As McElheny describes it, “The book is set of experiments in translation and scholarship. But it is inspired by a single, quite short story by Scheerbart.” This was followed by a film that combined aspects of this book and used the famous historic house of the Vizcaya Museum in Miami as a setting. The second book, a reader in part illustrated by myself and by Scheerbart himself, is called Glass! Love!! Perpetual Motion!!! A Paul Scheerbart Reader. Edited by Christine Burgin and myself. It presents to full books by Scheerbart, plus a number of his short stories and other texts by both Scheerbart and others.”

Josiah McElheny, Model for a Film Set (The Light Spa at the Bottom of a Mine), 2008. Handblown molded glass, painted cement, mortar, and wood. 37x 68 x 37.5 inches

I asked McElheny what attracted him to Sheerbart’s story. He learned about the story as a reference in passing and was “captivated by the summary.” As he tells it:

”Strangely, the story was in none of even the more extensive of Scheerbart's bibliographies. There is one bibliography with it and exactly three copies of the story in the US. A curator translated it live for me at a bar in Stockholm, after I had already committed to doing a sculpture, film, book, and performance about it. Listening to the full text of it at first, I was horrified. For example, I often describe Scheerbart as a proto-feminist misogynist. Suffice it to say, it was not what I was expecting. So I enlisted a number of collaborators to help me cope with the text.

“Through that process, I found that it did represent something I had been hoping for, dreaming of: an alternative to the triumphalist, capitalist, efficiency, and purity obsessed ideas of artistic modernism. Scheerbart described a dream of a better world that would always go wrong. That seemed like a good way of thinking to me. So first I tried to "critique" the story. Then I would say I just tried to understand it. Then I tried to "place it" in a context of its' own time and ours. Then I tried to find a way to turn it into images and art.

“I think that it is best characterized as working with history and working with historical material as if it can still speak today even if its' concerns are seemingly far out of date.”

I asked McElheny if he saw his project as a “conceptual adaptation”. “Yes, sure you can call the texts in the book "conceptual adaptations", or they might also be called "experimental translations" or "translations into parallel modes". Mostly it was an act of empathy, what might he have been feeling, why would he say these things? “

This last comment by McElheny highlights both the difference between artistic and scientific research and the value that a critical reflection, by way of an artistic response, can offer to existing or historic ideas. In this project, the artist acts not only as sculptor but also as editor, and convenor of discussions, and —as McElheny has always done— a critical historian.

It is also important to note that books are not best used as screenplays for works, but rather texts to engage, contend, and dialogue with. They are also not meant to be left as static, inalterable sources of truth. Going back to Friar William of Baskerville says about books. artistic research is not about taking a book and using its words as justification or gospel, but more as an object of study, adaptation, appropriation, resignification, or reinvention, producing in turn works to be reflected upon — and perhaps even written about.