Last week I was in Mexico City preparing an exhibition of past and present projects I have made that deal with pedagogy. I happened to be staying in Polanco, which is the very neighborhood where the school I attended from kindergarten to last year of high school is located. Not with a particular artistic purpose, but out of a personal need and because education itself was (as it often is) in my mind and almost purely out of the desire of walking (literally) down memory lane, I decided to spend a few hours revisiting the neighborhood where I spent my own early school years.

Polanco, an area adjacent to Chapultepec Park, was from its inception an affluent neighborhood in Mexico City. Originally stemming from the old Hacienda de Los Morales and developed as a modern residential area in the 1930s, Chapultepec-Polanco was adjacent to what was once pretentiously promoted by urban developers as “Chapultepec Heights” (in English) but later was renamed (by the disapproving nationalist government) as Lomas de Chapultepec. Styled itself as some kind of Mexican Beverly Hills, Polanco also and always had a high-end commercial character, as attested today by its many high-end boutiques, banks and embassies.

Because of the upscale nature of Polanco, I always feel slightly out of place there. Yet as fate would have it, this would be the place where my 3 siblings and I would go to school, thanks to the recommendation of its music teacher, Filiberto Ramírez Franco, who knew my father. The school, now known as Colegio de la ciudad de Mexico, was founded by exiled progressive Spanish educators and was mostly attended (although not exclusively) by kids from well-off families (many from the Jewish, Spanish and Lebanese communities in Mexico). My father made a big financial effort to put us through this school; I and my siblings owe a great deal to both my parents and the school’s dedicated and experienced teachers for the education we received.

The thing that is most ingrained in my brain from that neighborhood, aside from its colonial-style ivy-covered houses and leafy surroundings, is the actual names of the streets, mostly of European politicians, scientists, philosophers and authors, the latter which resembled the personal library of my grandfather circa 1940. It would appear that those who picked the names were the product of the Mexican Positivist philosophy of the turn of the century: names like Comte, Hegel, Cicerón, Aristóteles, Platón. The author street names were mostly 19th century romantics (Musset, Edgar Allan Poe, Victor Hugo, Lamartine, Tennyson, Eugenio Sue, Schiller) naturalists and realists (Dickens, Ibsen) as well as other, largely forgotten authors today like Sudermann. One of the very only streets (a small one) named after a woman author is of someone who actually wrote under a man’s name: George Eliot.

As in any school experience, what we learn is not just what is formally taught; most importantly we also learn to be in society. So it was against this background of 19th century authors that my teenage interests in literature started along with my share of the emotional turmoil that we all undergo during those adolescent years. My romantic life was a disaster all the way until I graduated from high school. Somehow I never learned the basic dynamics of dating and would get deeply nervous and clumsy around the classmates I was attracted to, which in turn made me, no doubt, even less appealing: a dork. So I and a few other friends gravitated toward cultivating a trait that in my teen mind was very aligned with the Romantic spirit: wallowing in self-pity and obsessing about unrequited love. It was almost as if I wanted to intentionally undermine myself so that I would masochistically enjoy my own misery.

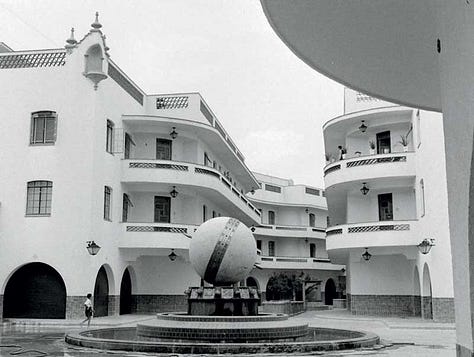

We all had key nearby places where we socialized. The central one was a sunny roundabout with a fountain at the center (“La Fuente”), directly across the school’s entrance, where we would gather after school. Sometimes we would cross the street to the Sugar Shack, a small fast food joint—run by Trudy, a friendly Dutch woman and her husband— that functioned as another school hangout. Some of my classmates lived in the neighborhood (Humberto on Homero Street, Jordi on Tres Picos, Ruy on Horacio) and I would often visit their places. I particularly shared the matters of the heart with Ruy, and we would have incredibly long conversations about it, which in my memory are intermixed with the ambience of the homes where we conversed. Once when we had to do a homework project after school Ruy took me instead to a mysterious little old gray and dark house on Lamartine Street, directly across from our school and adjacent to the Sugar Shack; a house where I assume he was staying at the time (and I never asked him why he was staying there). The house, made in the traditional colonial style and with its fence covered in ivy and hidden by bushy trees, was an odd place. While doing the homework in the dark dining room, you could tell, from the fluorescent light and noises coming out from the kitchen, that someone else was in the house.

Once, on a rainy evening at a pizzeria in one of our interminable conversations about our respective crushes, he remarked in a moment of clarity: “Isn’t it better to never get what we want? I mean, isn’t this better?” The implication was that, should one of us finally succeed at getting a partner, the dreaming would then be over. Paraphrasing Dante (another named street in Polanco), we enjoyed the idea of fervently desiring one thing without the hope of ever attaining it. It was a comment that defined that entire era for me.

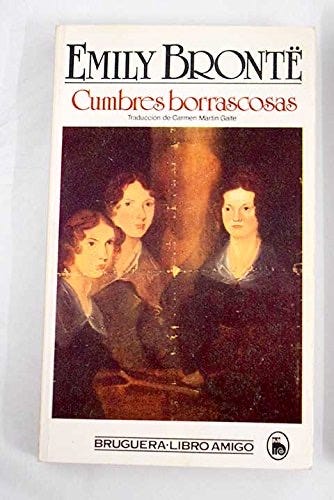

In the face of romantic rejection I gave myself entirely and intensely to drawing and reading —mostly romantic novels and poetry. At some point when my heart was particularly broken I got my hands on a copy of Cumbres Borrascosas by Emily Brontë, which I read intensely through a summer (which was a painful period for me because I would not get to see my crush for months). Summer being rainy season in Mexico City, the cloudy skies and the afternoon rain perfectly complemented my internal gothic state of mind. As I navigated, feeling almost like an eyewitness, the drama between the Earnshaws and the Lintons and the painfully entangled and intense love between Heathcliff and Catherine, I would walk down the streets and focus on any sight — a group of trees, the gray sky, a dull light onto a surface— that would help me visualize the scenes of that novel and transport me to 19th century England— a mental pilgrimage, if you will, from Chapultepec Heights to Wuthering Heights. On sunny days I would look at the textures of walls and shadows and project images from the Rubayat of Omar Khayyam and orientalist literature produced by the French authors like the ones imprinted onto Polanco’s streets. The larger fact here was that I, a Mexican teenager, intuitively sensed my own provincial isolation and desperately wanted to go out into the world to know it, thus the incessant wanderings of my mind.

It would not be until many years later, when I came to the US to study and was exposed to postcolonial theory that I became aware of the exceedingly Western-dominant, heteronormative and white-male intellectual tradition from which I had come from. I later realized that especially in the case of artists of my generation that grew up in the so-called cultural periphery was more the norm and not the exception. For example, I remember back in 2000 when I first met Lebanese artists and filmmakers Hisham Bizri and Akram Zaatari at a conference in Athens, I was struck by the resemblance of our mutual Western-dominated education in Beirut and Mexico City respectively. Hisham and I discovered that we both had memorized the exact same passage from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, Ana Livia Plurabelle, recorded by Joyce himself in 1929. (Hisham could recite it flawlessly in Joyce’s exact own accent and cadence, way better than I ever could: “Tell me, tell me, tell me, elm! Night night! Telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of. Night!” ). When becoming an artist in the periphery, one develops an even greater urgency to learn and master Western tradition in order to enter and hopefully influence the dominant cultural discourse.

Speaking of memorization, I later noted another fact about myself that involves the topography of Polanco and of which I have no control. Often when I read, deeply study a text, or have to learn a script by heart, my mind instinctively reverts to mnemonic loci, often visualizing some of those very streets of Polanco. There is never any direct relation between what I am reading and the mental images, but the narrative happens to evoke different corners, the ivy-covered stone walls, the sunny gardens with dark shadows created by that extraordinary high-contrast midday sunlight of the Mexican highlands, the forged-iron windows, the Californian architecture, the churrigueresque-style gables. It is the embodied architecture of memory that can’t be extricated from experience, just as it happens the childhood home: the places I am familiar with where, in almost a subconscious way, I can place ideas, phrases, words as if in a bookshelf.

Back to this past Saturday evening, the day before I went back to New York: in spite of the usual August rain, I had the urge to walk through Polanco and revisit in person those streets that permanently reside in my subconscious.

As I start walking, my steps take me to my old school down Lamartine Street and Campos Elíseos. The school’s metal doors are now painted in austere grays and blacks, not like the olive green which was also the color of our grade school uniforms. The red brick benches on the sidewalk, where we would place our back packs while we waited to be picked up, still exist. I would often stand there as I would watch every day at school’s end, a black Lincoln car coming by to pick up my crush, to whom I never even dared to speak a word. My mind is exploding with memories. La Fuente is also still there ( the place where I did one of my first performance art pieces in 1994 consisting in a choreography in the water, umbrella in hand)— the roundabout today surrounded by very high trees.

As I go around the block on the side of the elementary school, in the corner of Campos Elíseos and Hans Christian Andersen, I see that someone has painted a quote from the Danish author onto the street: “Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with short steps.” Ironically, I reflect, I am walking after the child that I once was and who long ago walked away from there in big strides. Sentimentality aside, I am glad that this is the case.

I don’t have an umbrella and I am getting soaked. I walk back to Lamartine and I call an Uber. I take a last look across the street: the Sugar Shack is gone, and in its place and the adjacent lot there is instead a fancy upscale restaurant. But the old ivy-covered house where I once visited Ruy is still there. The lights are on inside.

I get in the car amidst the Wuthering storm. I don’t want to ever ask Ruy why we went in that house that day. Sometimes the hope of not attaining the full details of a memory, of not ever knowing, is better. Don’t tell me, don’t telmetale of stem or stone. Beside the rivering waters of, hitherandthithering waters of.

This time you really got it round!!!!! love it!!!

Qué bonito recuento de esa etapa tan importante de nuestras vidas, Pablo.