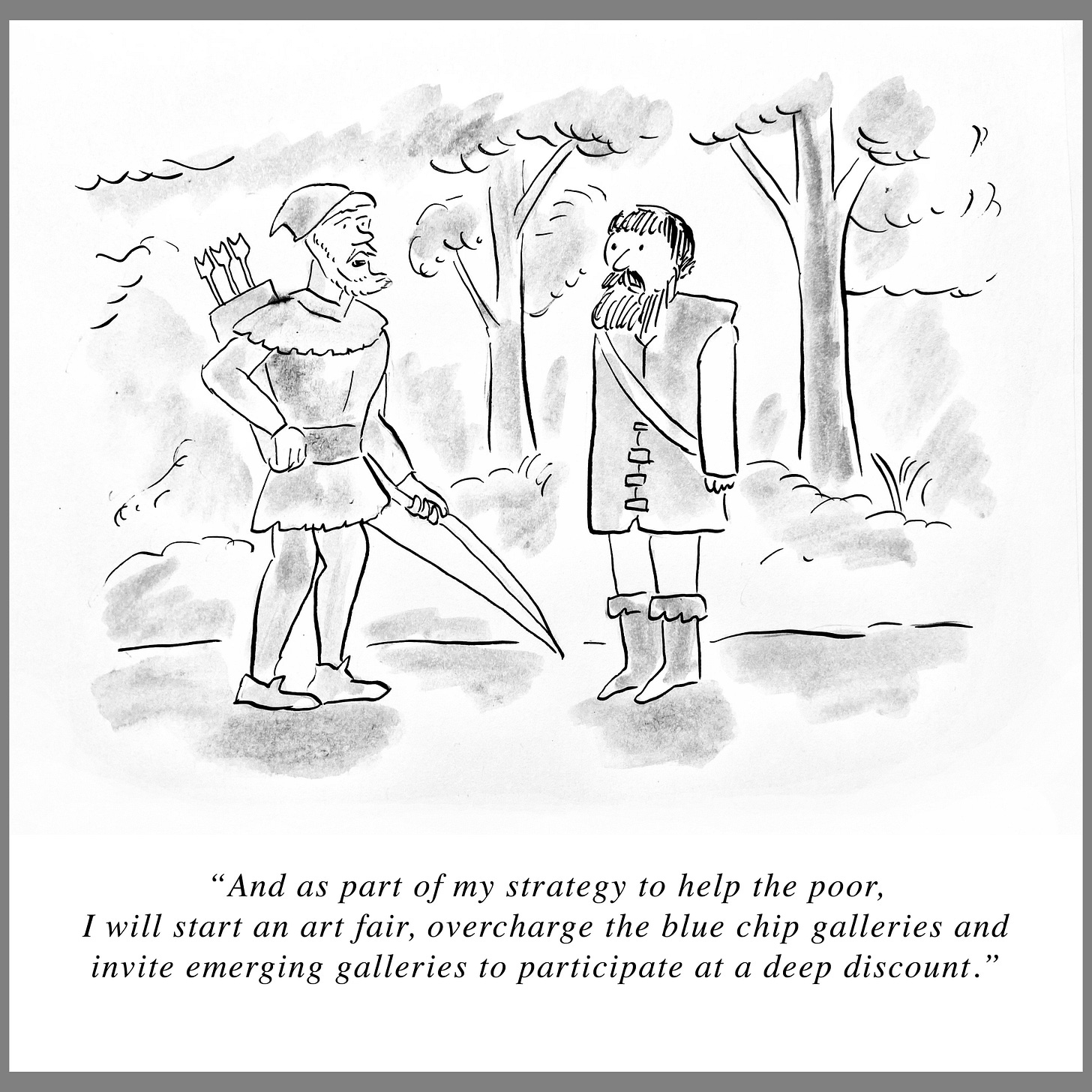

Rob Blockbuster Peter to Pay Alternative Paul

Balancing the art that sells with the art one wants to do.

As a young museum educator, I was trained to teach in galleries using a formal interpretive analysis approach known as Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS). The inquiry-based system, which loosely follows a version of the Socratic method, boils down to three basic questions: “what do you see?”, “what do you see what makes you say that?”, and “what else?”

This methodology is tricky to use when you are interpreting non “retinal art” (as per Duchamp’s term), but that detail notwithstanding, just for the sake of entertainment (and some education) I would like to invite you to do a brief exercise with me using VTS— albeit not with a Mondrian or a Kandinsky, but with museum websites.

Go to the website of a large art museum that does both modern/historical and contemporary exhibitions; a museum large enough that can have at least two temporary exhibitions at a time. What do you see? What is it that makes you say that? What else?

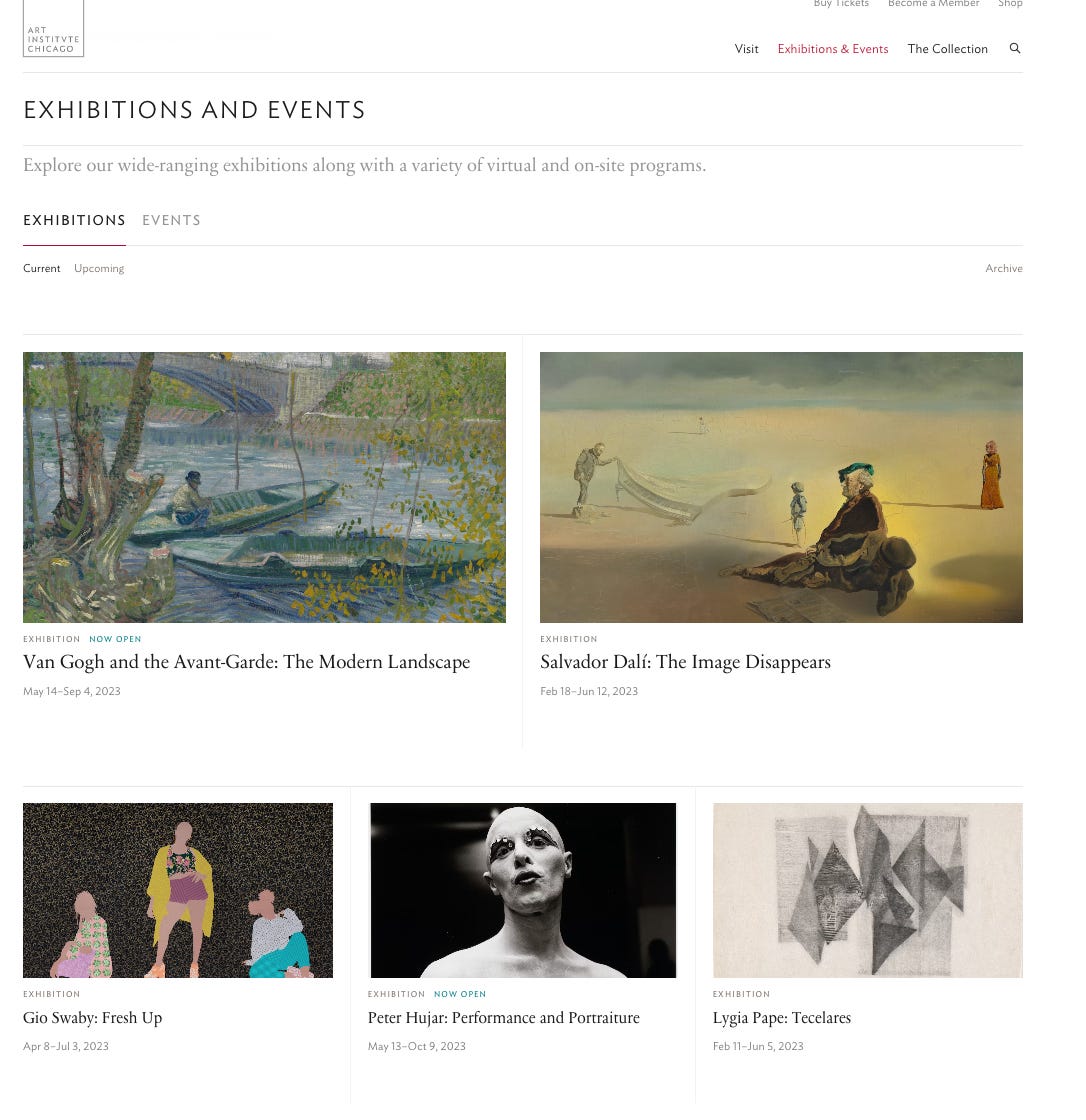

What do you see? What you are most likely to encounter is a balancing act in the exhibition program. A blockbuster show that is guaranteed to bring in crowds (Monet, Picasso, Dalí, Van Gogh, O’Keefe, etc.) next to a contemporary art exhibition with a more cutting-edge theme and/or engaging with current political or social issues. Let’s take a look at the Art Institute of Chicago’s website right now: the two top featured exhibitions at the Art Institute right now feature Van Gogh as a header and Salvador Dalí, with a second tier featuring Peter Hujar, Lygia Pape and Gio Swaby, an emerging Black Bahamian contemporary artist.

What do you see that makes you say that? you see that balancing act because leading art museums have two equally crucial goals that they need to consistently meet in order to subsist.

One of them is to build a revenue-generating client base and brand loyalty. Like the next-door diner, the menu is standard, consistently meeting expectations. Now, In museums, the strength and focus of their collection partially determines their menu, which allows them to always offer the same fare but with slight variations. Case in point is the dozens of (revenue-generating) Impressionism exhibitions that the Art Institute of Chicago has organized throughout its history, with a major emphasis in Monet. As audiences have predictable taste for the same fare (Monet/Van Gogh/Picasso/Matisse) to expect otherwise or to try to bend audiences to your will is a recipe for disaster. And those names sell: you only need to see the museum gift shop with its sea of George Seurat mugs, Monet box cards, and Marc Chagall scarves.

At the same time, large museums can’t position themselves as leading cultural institutions if they do not also engage with the art of the present and current issues. This is critical to maintain their reputations in the art world and also guard their role as anointers/canonizers of artists that will be the artistic references of the future— otherwise they become mausoleums. So keeping the Monet 24/7 model as sole formula is problematic because while these are crowd-pleasing, uncontroversial shows, they also mostly feature dead white male artists; furthermore, the meat-and-potatoes names that really bring in the crowds are very limited: in terms of 20th century art the names also boil down to a dozen or so artists ( first tier like Picasso and Matisse, then Warhol, Kahlo, Kusama, and so on). I am sympathetic to curators in those museums who are tasked with constantly trying to find new themes to rehash those works for blockbuster consumption. When you take a look at those exhibitions, you will note that the vast majority are monographic shows, and/or have a slight thematic emphasis that is not wildly adventurous (“Picasso sculptures” or “Matisse prints”). So if we had the ability to use VTS to interpret the museum’s books, if it did it would reveal that the financial balancing of those books is dependent of the blockbuster show being able to finance the contemporary program.

What Else? The Peter/Paul (or blockbuster/alternative) combination works in some, but not all respects. It usually works in that emerging show positions the museum in a stronger place as a forward-thinking institution, which the mainstream show cannot do. A less sound rationale is that the large crowds might come primarily to see the mainstream artist and then be introduced to the emerging one— which might be truer in theory than in practice. I once unexpectedly found myself in such a situation in 2012, when I had a solo show at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City; the other main exhibition was one of works by Fernando Botero. As one could imagine, the Botero show received enormous crowds, a tiny percentage of which happened to bump into my show along the way. But the nature of the works I was presenting was too conceptual an art insider-y, oriented to a contemporary art audience, and so antithetical to a Botero-friendly sensibility that I would doubt that a single visitor of the tens of thousands who specifically went to see Botero at that time would have cared about, or even remember, my show at all.

I should also note that the vast majority of curators in museums are not fond of doing blockbuster shows. They provide limited opportunity to generate new scholarship, they feel (and are) predictable, they involve arduous work with little intellectual discovery and there is a gigantic gap between the audiences they generally serve (i.e. affluent tourists and non-art professionals who see art mainly as entertainment) and the professional art community who these curators have greater affinity with ( and who, like them, generally want to see more experimental, thought-provoking shows).

Thus the prevailing model that I have described as “Rob Peter to Pay Paul”, a phrase that comes down to us from the Middle Ages and appears already in use in the writings of François Rabelais, supposedly a reference of a historical anecdote of how one wealthier church (St. Peter) was subsidizing another (St. Paul), which is also why the term is sometimes referenced in the idiom “maneuvering the apostles”.

In the US arts system at least these are vital strategies: Most museum budgets heavily rely on private/corporate memberships and admissions revenue, which normally amount to about a third of their annual budget, in addition of about 10% from store and café sales (which are of course largely dependent of attendance). So, while I am sympathetic with the demand that museums should be much less traditional in their programming and engaged with issues that concern both the progressive and art world intelligentsia, the reality is that solely focusing on a program like that will not meet the annual museum’s revenue goals nor, perhaps, best serve non-specialist audiences.

A useful analogy to the Peter/Paul strategy can be found in Amy Whitaker’s book “Art Thinking”, which focuses on creative strategies to improve one’s work. In a chapter titled “To Make a Boat”, Whitaker describes the balancing act between the creative projects that one wants to do with what she describes as a “couch” or, “the economic scaffolding on which the pilot projects—the throw pillows— are safe and secure.” Pursuing a career where you jump from one creative project to the next without a long-term strategy is one that she describes as “all throw pillows and no couch.”

I asked Whitaker whether her analogy might hold in museum programming. Can we say Monet is a couch and the more alternative/contemporary artists are throw pillows? And how else could be define the Peter/Paul phenomenon in economics? Whitaker agreed with my comparison (to my relief, as I didn’t know if my analogy was too absurd) and then she said: “ the term “cross subsidy” might also apply — an institution uses revenue from one area to cross subsidize another activity”, adding, “What is especially compelling to me about the couch metaphor is that it speaks to art making as an act of investment — particularly championing emerging artists.”

Whitaker also reminded me that in her book she also uses the notions of “cash cow” vs. “question mark”, referencing revenue-generating projects that one does (cash cows) and how we use those to engage those that we believe in but whose outcome is uncertain (question marks).

You can in fact see the entire art world through this lens, VTS-style, and learn things. The alternative/emerging galleries section of every art fair are the “Paul” sections, largely subsidized by “Peters”; secondary market sold by some galleries under the table helps fund their cutting-edge program. Eflux, the famous art world publishing platform, ostensibly uses its online ad revenue to finance its publications and programs which have a rigorous curatorial criteria. And so forth.

And historically there have been cross-subsidy art projects that did not pan out. Perhaps the best known was Guggenheim.com, created still during the dot.com bubble years and under Tom Krens’s leadership, in the hopes of becoming a for-profit venture of the brand. I remember the museum’s Deputy Director at the time talking at a meeting about how they had created a “legal cathedral” to successfully separate the for-profit dot.com venture from the non-profit museum. In the end it was not to be. And—this is such a poetic irony— if today you happen to google “Guggenheim.com” it leads you to A Better Guggenheim, a site with content shared “with the express purpose of revealing the inequitable structures at the Guggenheim.” The site was made, one is to assume, by Pauls who have felt robbed by Peter.

Last but not least, there are those artists who make a type of work that fund the rest of their practice. In a past column I have written about what Whitaker describes as “cash cows”, works that become “hits” and generate demand for more of its kind (which can be problematic). What many artists do is to rely on their commercially successful work to finance the work that they are most personally invested in — work that for whatever reasons (too new, too esoteric, etc.) has not received the same level of support. It is well-known that Christo and Jean-Claude funded their own public art projects from the sale of Christo’s preparatory studies, but Christo also relied on the sale of some of his early works from the 1950s and 60s.

There are two primary questions around the Peter/Paul strategy. The first concerns the implications around ethics of transparency. While museums would never publicly say that their revenue-generating shows help pay for their non-revenue generating ones, they always fundraise for education (the “sad puppy” of museum fundraising), but in reality they secretly use a “rob from Paul to pay Peter” approach, often taking education funding and redirecting it to what we used to call “The Big Pot” (general museum operations), which at the time of creating the annual budget then get allocated favoring expenses that are not necessarily specific to education. Funders should be (and some thankfully are) much more proactive in insisting that their funds go directly to benefit the projects that they supported and condition their donations with the right to see the receipts.

The second and last question concerns this strategy’s impact on institutional/artistic identity. We must not forget that artists, as well as museums, are not judged just by a single activity but by the sum of their parts. Even if mediocre works or exhibitions can subsidize laudable ones, we can’t always selectively praise one while altogether ignoring the other. In Mexico we have a saying: “aunque la mona se vista de seda, mona se queda” (“even if the monkey dresses in silk, the monkey remains.” ) If Monet is the monkey and alternativity is the silk dress, we will still see Monet’s coffee mugs (and silk scarves) in the gift shop. Seeing a push to monetize crowd-pleasing art is what makes me say that. What else?

these are the awesome-est! Just had to share re: art making money

https://www.amazon.com/Helmeted-Monster-Hieronymus-Earthly-Delights/dp/B002SVONDY/ref=asc_df_B002SVONDY/?tag=hyprod-20&linkCode=df0&hvadid=647626624266&hvpos=&hvnetw=g&hvrand=8037453502198908691&hvpone=&hvptwo=&hvqmt=&hvdev=c&hvdvcmdl=&hvlocint=&hvlocphy=9021720&hvtargid=pla-829642263960&psc=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwmZejBhC_ARIsAGhCqnfYy7Yp6i8s1SVVrt2cZB2by1NHER5fFG8u42NwUXU0fdOvYIJXQOUaAh0TEALw_wcB