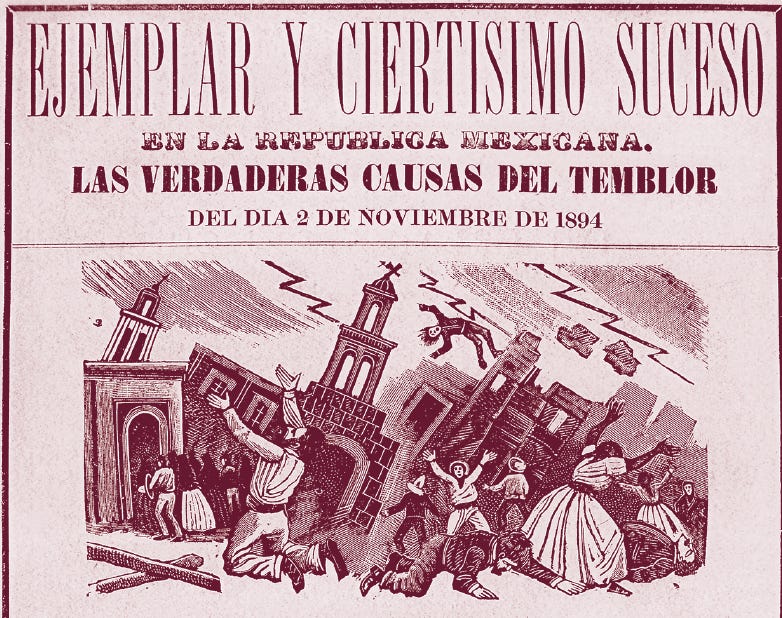

José Guadalupe Posada, illustration for news pamphlet, Horrible Temblor (Terrible Earthquake), describing an eartquake in Mexico on November 2, 1894. Imprenta Vanegas Arrollo.

This past Monday, September 19th, 2022, there was a powerful earthquake in Central Mexico. Temblors are unfortunately not an uncommon occurrence in Mexico given the alignment of the North American and Pacific plates, as well as the smaller Cocos plate. In fact, the country is shaken almost every day, but seldom with the strength or length for most people to notice it.

What was unusual about last Monday’s earthquake was the exact date when it took place: it coincided not only with the date of another powerful and destructive earthquake on September 19th, 2017, but also with the devastating, 8.1 magnitude earthquake that occurred on September 19th, 1985, which leveled many buildings in Mexico City and resulted in the deaths of about 10,000 people.

I was in Mexico City on the morning of the 1985 earthquake. I was 14 years old, and my family and I were having breakfast as usual before my father would drive me to school. At 7:17am the entire house started to rock like a boat. Our dog ran all over the house, terrified. Two large decorative plates hung on the living room were bouncing violently. After it passed, we breathed a sigh of relief and resumed our day as usual. Since it was the era before the internet, we did not realize the amount of damage the city had endured until much later in the day. During the following days life as usual was suspended and we all got involved in rescue and volunteering efforts.

When the 2017 earthquake occurred, many relived the traumatic memories of the 1985 earthquake — and ironically, on September 19th of this year there were a number of earthquake drills shortly before the real earthquake, causing people to believe, when the real earthquake alarm rang shortly after, that it was a continuation of the same drill. Everyone saw the coincidence.

This third time, when yet another tragic natural event hit Mexico on the exact same date, the coincidence no longer felt like a coincidence. The repetition in pattern of certain natural events might follow a certain rationale: for example, hurricane Fiona, which just struck Puerto Rico, came within days of the 5-year anniversary of the devastating hurricane Maria but both happened within the calendar frame of hurricane season, which is sadly now increasingly predictable. But there is no such thing as an “earthquake season”, regardless of climatic conditions.

The Hotel Regis in downtown Mexico City after the September 19 earthquake, 1985- photo by Enrique Metinides

As a result of the September 19th Mexican earthquakes, and even while seismologists adamantly argue that they are indeed a coincidence, inevitable attempts to explain it have emerged. Some news outlets report that people are now superstitious about the month of September, especially after this week all but expecting from this point forward that every September an event like this will happen. Others draw from specific pseudo-scientific explanations about earthquakes in general: a Spanish new age author argues that earthquakes occur when there is an unbalance between the level of consciousness between groups of people (“in the universe, everything that is unbalanced tends to get re-balanced one way or the other”).

The other reaction, in typical Mexican humor, is to post things in social media such as “the Catholic Church has now officially designated September 19 as the saint day of San Goloteo” (“zangoloteo” in Spanish means “shaking”).

And yet there is one more— the one that particularly interests me— which is to look at art and literature. One of the works that has been making the social media rounds this week is the 1953 short story by Juan Rulfo titled “El día del derrumbe” (“The day of the Collapse”) which starts with a conversation between two people who are trying to remember the exact date of an earthquake that took place between September 18 and 21:

This happened in September.

Not in September of this year but in September of last year. Or was it the prior year, Melitón?

—No, it was last year.

—Yes, yes, I remembered it well. It was in September of last year, around the 21st. Melitón, wasn’t it on September 21st the day of the earthquake?

—it was a bit earlier. I believe it was around the 18th.

While fascinating, neither I nor most people I respect are interested in playing a parlor game or art as prediction of natural or political events. But when we find ourselves in situations where artworks from the past that suddenly become prophetic or accurately describe our collective lived reality they become important not as religious oracles but rather as clarifying reflections that can shed light onto what we are living.

Most vivid and present to all of us (still today, I am afraid) is the pandemic, and the many artistic references that we resorted to make sense of our situation. Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Year of the Plague and Albert Camus The Plague were clearly the most obvious, although the takeaways are different: Defoe’s narration focuses a lot, as an English professor noted, on “the numerous charlatans, quacks, frauds, fortune-tellers, and dreamers of false dreams who tried to sell the credulous unproven nostrums, hopeful astrological predictions, or useless practices. They join other purveyors of false claims, unrealistic optimism, misinformation, rumors, and unsubstantiated tales.” Camus’ novel, in contrast, while highly visual and descriptive is nonetheless a much more metaphorical use of the plague more toward a political statement— one which, at least in the United States, resonated even stronger with us as concurrently with this health crisis we have also endured another pandemic of a good portion of the nation descent into embracing authoritarianism.

However, the pandemic has been one in a lifetime event, and the subject at hand is the repetition of a particular event, and our desire to find meaning those repetitions.

Here I would like to point out a particular pattern that has applied in some interest way to the history of my family.

Trinidad García de la Cadena (1823-1886)

Trinidad García de la Cadena, my great grandfather, was the governor of the state of Zacatecas. In 1880 he ran unsuccessfully for president and shortly after started a campaign against the indefinite reelection of dictator Porfirio Díaz, eventually leading an insurrection against him. He had as one of his close collaborators the colonel Juan Ignacio Lizalde, who was younger as well as a protégé of García de la Cadena who some thought (erroneously) to be his son. In 1886, Diaz ordered García de la Cadena apprehended. Both Lizalde and García de la Cadena were executed in cold blood while in custody at the train station of La Calera on November 1, 1886.

Many years later, my maternal grandmother, Luisa Elena Chávez Ramirez, and my maternal grandfather, Ignacio Lizalde, met. At some point, by sharing family histories they realized that their grandparents had met the same fate on the same day while fighting for the same cause, on the exact same spot, alongside each other. No one could have ever imagined that the offspring of general García de la Cadena and Coronel Lizalde would end up coming together and forming a family (and confirming the perception at the time that indeed they were related). I am the great-grandson of both of those two men.

I often thought about that coincidence when, for a brief period of time in our family in the 1980s, whenever an older member of my father’s side of the family would pass away we would, shortly after (within a few weeks), lose an older member of my mother’s side of the family as well. This happened more than a few times. The patterns created confusion and puzzlement amongst us. Had they continued, like the Mexican earthquakes, they would have probably made us superstitious as well.

When Gabriel García Márquez delivered his Nobel prize lecture in 1982, he made a case for the idea that when you describe factual events in Latin America it often appears that you are writing fiction. In a humble statement, Gabo argues that he is a mere scribe of reality: “Poets and beggars, musicians and prophets, warriors and scoundrels, all creatures of that unbridled reality, we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.” It is not too dissimilar from the many statements by other writers, like Breton, now cliché, about how surrealism was an organic product in Mexico, while the French had to invent it.

I do not believe, as much as I wished to, that those singular events, sometimes repeated, may not be cosmic alignments. We might invent superstitious interpretations or read spiritual messages into them but regardless of their reason of being, what is true is that their alignment in itself is a form of art: readymade circumstances.