Strange Smiles and Ardent Reason

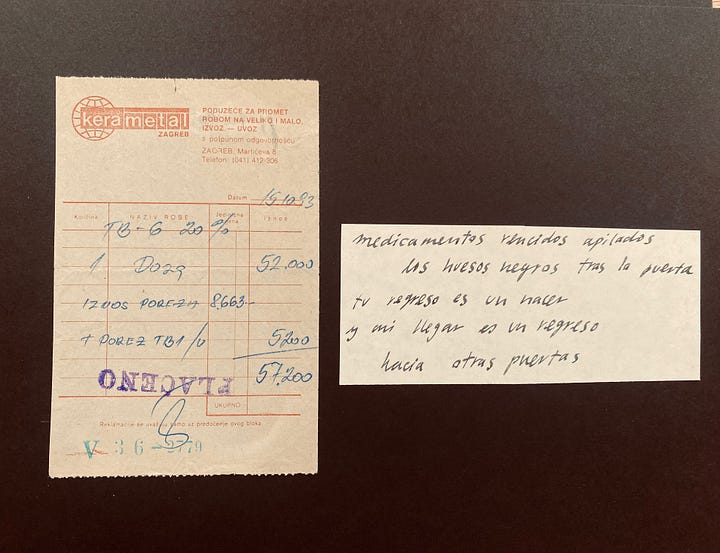

Croatian memories, a student sketchbook, and the summer of 1992

Dublin, July 4, 2024

Vlatka Horvat

Croatian Pavilion

Venice Biennale

Dear Vlatka,

Thank you so much for inviting me to participate in your collective drawing project “By the Means at Hand” at the Croatian Pavilion of the 2024 Venice Biennale. It was a very meaningful invitation for me, not just because your project is about the exchange and communication among artist friends but because it specifically involves you, someone I so respect and admire, and Croatia, a country with which I have a long and deep relationship. I already wrote you a small letter with my contribution to the exhibition, but I am sending you a more comprehensive response now because there is much to say regarding our shared Chicago history as foreign art students, Croatia, the ardent desires triggered by the summer season, and my personal obsession of about a decade with an 18th century lithograph, all of which better explain my contribution to your project.

Summers in Chicago, as you know, are extreme in their scorching heat and humidity. In the summer of 1992, I was an intern at the Art Institute of Chicago, working in the comfortably air-conditioned and quiet office of the eminent Aztec scholar Richard F. Townsend, then head of the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas. That fall we opened the exhibition Ancient Americas: The Art of The Sacred Landscapes. My job was to proofread object labels and corroborate dates, credits, and accession numbers (a menial and tedious task, but I did it with great joy). During lunch I would walk down Michigan Avenue toward the Chicago Public Library (now the Chicago Cultural Center) and would spend the hour reading poetry. One of the books (which in shame I confess I never returned) was Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet (O Livro do Desassossego). I admired Pessoa’s brilliant literary solution to what might have been a condition of dissociative identity disorder; I, too, instinctively felt that I was evolving into different identities.

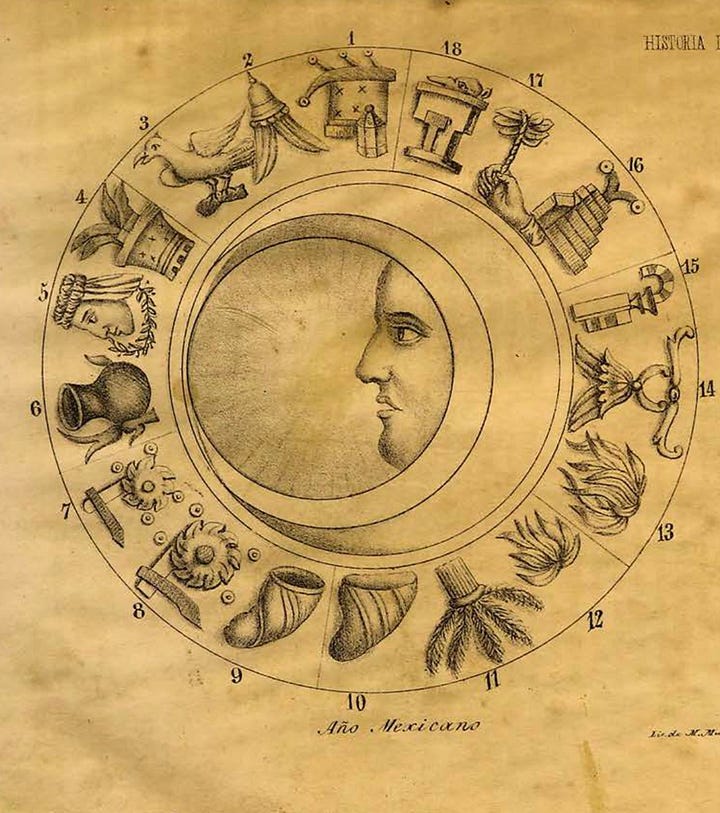

I experienced separation anxiety from Mexico, which made me devour every book of Mexican poetry and literature I could get my hands on. One book in particular that I frequented, Octavio Paz’s Vuelta (an anthology of his poetry published by Editorial Seix Barral in 1976) had a colonial-era image of a sun in its cover that intrigued me; it was a lithographic illustration pertaining to the Aztec calendrical system found in the Historia Antigua de México, assembled by the Jesuit scholar Francisco Javier Clavijero in the 18th century. While recently checking the actual illustrations in the original Clavijero volume, I realized that the designer of the cover of the 1976 Paz book had rotated the sun image to the right ( likely a nod to the book’s title), which is why it was hard for me to locate the image online in the first place.

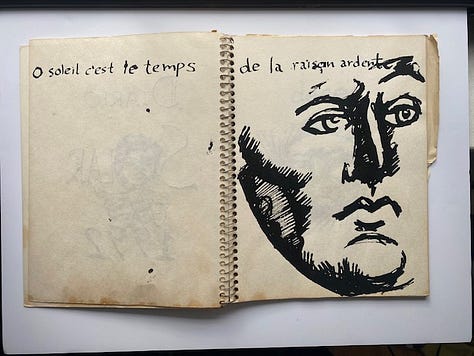

I still can’t quite figure out why that single image of the anthropomorphic sun had such a powerful effect on me. I had been influenced at the time by certain surrealist/dada works that drew from historical material with collage and assemblage (Ernst, Cornell, Schwitters, Raoul Hausmann), the mysterious Mesoamerican smiling faces from the Remojadas culture in Veracruz, the esoteric work of Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, and by some neo-figurative Mexican painting from the 80s that drew from scientific illustration and hermetic symbolism (also, incidentally, the Aztec calendar representation of the sun was appropriated by George Maciunas for one of the Fluxus manifestos). I surmise now that the facial representation of a planet came to represent the approximation of understanding and relatability of something that feels unattainable, vast, abstract and ultimately unknowable — not unlike the illustrations of some science textbooks I had in school that were visually so attractive to me, but the concepts they illustrated so hard to understand. There was, also, my draw toward the uncanny, such as the landing scene in George Melies’ A Trip to the Moon.

1992 was the summer of desire for me. But if was not only a season of romantic desire — and I sure was in love with the idea of love itself, clumsily falling into one unrequited love situation after another. It was also a season of a fervent desire to know, convinced somehow, that success as an artist depended entirely in learning, as if that the accumulation of knowledge alone could an artist make.

That summer I was learning French and memorizing Rimbaud, Mallarmé, and portions of Apollinaire’s famous poem La Jolie Rousse (“O Soleil, c'est le temps de la raison ardente”) which resonated with me in how I struggled between experimentation and tradition with my ultimate desire to embrace the unknown.

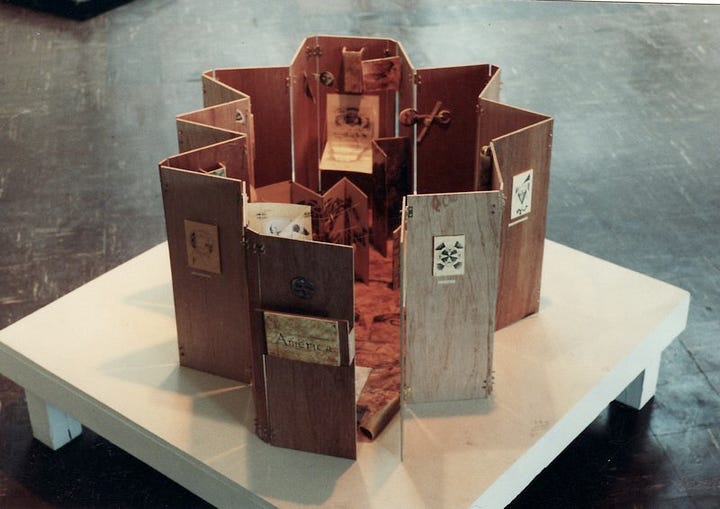

I entered around that time in a competition organized by the Italian government to “celebrate” the 500th anniversary of the encounter of the Americas. I submitted a conceptually baroque piece titled “America” , a wooden structure in the form of a book that, when opened, it would become a sort of small architectural installation. The strange structure I made won a first prize, which included a flight to Italy. The piece was populated by solar imagery and other symbols that referred to an overwrought, epic, metaphorical poem I had written, laden with symbolism. Years later— and I did not realize this until a few years ago— I found the sketches to that object that I had made in 1992, which bore a striking resemblance to the (also) collapsible schoolhouse I designed in 2005 for The School of Panamerican Unrest. Sometimes certain ideas are engrained in our brain and reemerge in unexpected, unconscious ways. Even the eye of the project, in its masonic references, is a small not to the anthropomorphic sun I was once obsessed with.

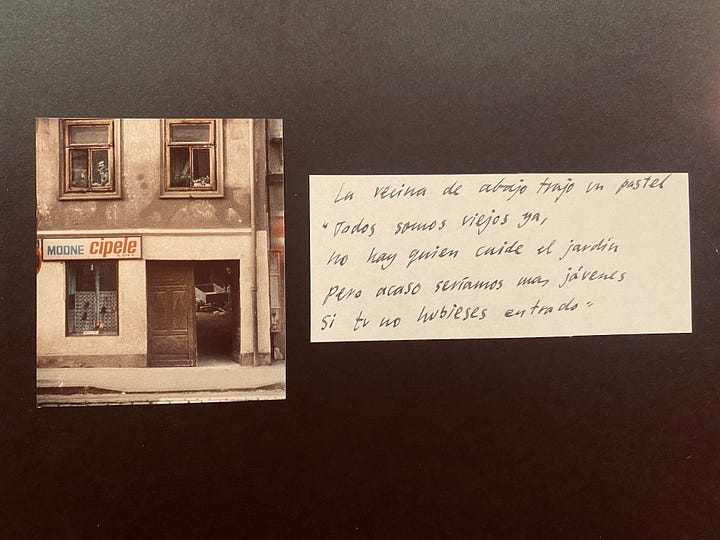

The fall of 1992 I finally started a personal relationship; she was from Zagreb, Croatia, a fellow art student at the Art institute of Chicago. The following summer, in 1993, she went home and I used the ticket I had received from that Italian competition to visit her there. The Yugoslav war was raging at the time; I remember boarding the train in Venice (after seeing the 45th biennale which included Hans Haacke’s famous piece Germania), which, after arriving in Trieste, got depleted of passengers as it headed toward Slovenia; I was practically the only passenger left on the train. The crossing into the ex-Yugoslavia, before the break of dawn, felt like entering into a different world: the colors, the materials and the textures of the Eastern Bloc (even while the Ex-Yugoslavia was a non-aligned country) felt acutely in contrast with anything I had ever experienced before. We were taken down from the train by armed soldiers and the train was thoroughly inspected. UN tanks and military vehicles were everywhere; the Croatian army was making critical advances against the Serbian forces in their war of independence.

Over the course of that decade, I developed a special connection with the city of Zagreb, it being the first city in Europe where I exhibited as an artist, first in the Zagreb Youth Salon and later individually (thanks to curator Janka Vukmir, Director of the institute of Contemporary Art in Zagreb; when I asked her regarding the latter she said, “if I remember well there had been organizational hiccups and you weren’t too happy but still excited about having a show”). The relationship fueled a lot of my ideas for future projects ( The Instituto de la Telenovela, focusing on the impact of Mexican soap operas in Eastern Europe, among others).

As you know, we met in 1998 in Chicago, shortly before I left the city for New York. You invited me to do a performance at Northwestern University where you were doing an MA in performance studies and where, as I recall, did a piece about Fernando Pessoa (the poet I avidly read in that 1992 summer and whose term, “desasosiego”, I borrowed for my Panamerican project).

There are interesting parallelisms between Croatia and Mexico: two Catholic countries with centuries-old traditions that were subsumed under a foreign empire (Spain for Mexico and the Austro-Hungarian empire for Croatia, although in Mexico we did have an interesting thread in the fleeting French monarchy of an Austrian: Maximilian of Hapsburg). From the beginning I instinctively recognized the cultural echoes produced by that parallel history, and the peculiar place that both Eastern Europe and Latin America occupy in constructing their own reality from the center. That self-construction is to me, in its eccentricity, more interesting to me than the models it seeks to emulate. And even though I have lived for more than a quarter century in a city that sees itself as the center, I am, and will always be, more interested in the margins.

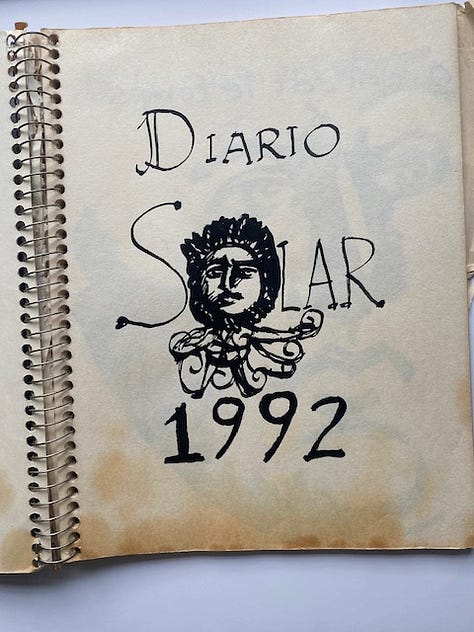

I thought a lot about what I could contribute for your project, which invites your artist friends to submit a drawing, delivered by hand. In the end, and in the spirit of the subject, “By the Means at Hand”, I concluded I needed to submit something by the means of what I had at hand, as well as something that is connected to my (our) student years in Chicago and my initial relationship with Croatia. I thus enclose my sketchbook from that scorching summer of 1992, where my solar obsession started and is documented.

It has been by my bedside for years, and I have not been sure what to do with it. Youth sketchbooks are mostly embarrassing for artists. But for me they are more like archaeological relics. I did not know what to do with it, but it now, not least by virtue of it being the means I have at hand, I believe it is the fitting work to contribute.

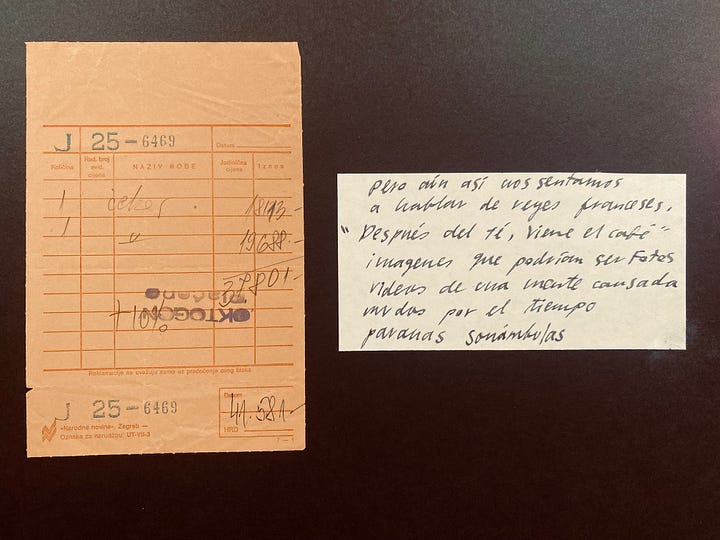

I end with a few entries from my diary of the summer of 1992. I wrote it as a letter to my future self. I hope compassionate readers can see this as the late-night ruminations of a young, vulnerable art student trying to understand their present and find sympathy from their future interlocutors.

S toplinom sunca sam ti poslao veliki zagrljaj, i dok se upravo vrtimo oko sunca, veselim se našem ponovnom susretu u jednom od tih okretaja.

Pablo

---

May 9, 1992

I write between exhaustion and exhaustion, as if it were between walls, between parenthesis. Things haven’t changed since I started these diaries five years ago. I have changed countries, but my naiveté remains intact.

July 11, 1992

There is no time to analyze everything. Sometimes we need to let our intuition do the work.

July 17, 1992

I want to learn to be more stoic. Not allow myself to be overtaken by immediate desires, which appear appropriate at first but generate trouble later. I want to forget, for once, that time goes by. What is more important is to learn to breathe through making.

September 7, 1992

Clear morning. Confused dreams about loving someone who doesn’t exist. Dialogues with absence.

Aren’t metaphors nothing but the offspring of interpretive rhetoric?

I am 21 years old and things seem to go very fast. I am not a promising kid but only an acceptable post- adolescent, and tomorrow, an average adult.

I have the feeling of having found something infinite: the world of my obsessions and my memories. I feel as if it has an end point, but in fact it never finishes. It is about deciphering oneself.

Sometimes I think it is not necessary to understand what I am doing; maybe I should just do it and I may understand it later.

I have started to abandon what books say. One has to balance things.

It’s 1:12am right now and I am in bed, with a book by my bedside, with a fresh breeze coming through the window. A car passes by, with a sound similar to the one of my aunt Elena when she came to visit us. I am tired but want to wake up early tomorrow.

Tomorrow is what You are reading about today. I am writing to myself, and I am writing to You.

__