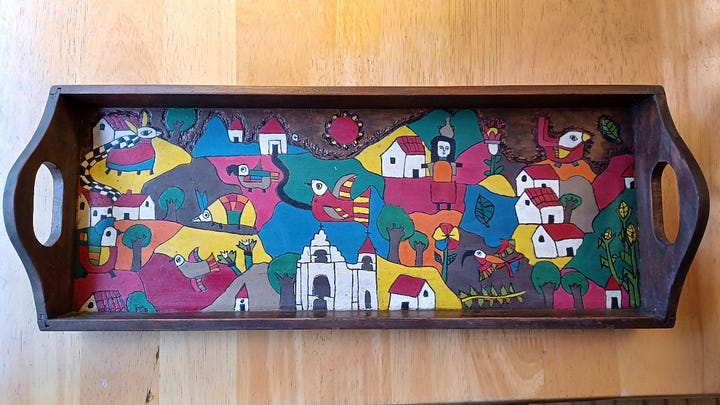

As a kid growing up in Mexico in the 1980s I used to attend a summer camp run by my aunt named Casa Abierta. There we would participate in a whole range of activities which included music, theater and crafts, including a class of pirograbado (pyro gravure), which is a decorative wood-burning technique using a hot metal stylus onto surfaces like the ones of boxes, trays and trivets.

The imagery that we would use as model to reproduce came from a series of colorful compositions inspired on traditional crafts that one would often see in people’s homes in Mexico in the 70s and 80s; these were simple depictions of country village scenes with big-eyed birds, butterflies, flowers and red-roofed houses; the only thing we knew about them was that they were crafts from El Salvador. My sister was (and has always been) excellent at making these and other crafts, and still keeps some of these items at home, both the original craft pieces purchased in the 1970s and the ones she made herself.

Many years later, when I actually visited El Salvador and other parts of Central America, I encountered those same designs again in tourist areas, airport shops, and beyond. But what I also learned was that this type of craft did not have a long history, but that it all started as inspiration from the work of a single artist, Fernando Llort (1949-2018).

Llort was born in San Salvador. According to various biographical accounts, he briefly studied architecture and always made art, but the majority of his studies were dedicated to theology— first in Medellín, Colombia, later in France and Belgium and finally in Louisiana in the U.S., where he pursued art more formally. In 1971 he returned to El Salvador for good. “He was part of an anti-system group”, Salvadoran artist Ronald Morán told me. “he was part of a very organic movement, influenced by hippie culture and liberation theology.”

Fifty years ago, El Salvador did not really have a folk art tradition of its own. It being the smallest country in the continental Americas, over the course of its history and at different moments El Salvador has been subsumed both politically and culturally by its much bigger neighbors Guatemala and Mexico, both of which are folk art powerhouses. Llort was influenced by Maya culture and modern art, but sought, as any other artist does, to create a visual language of his own.

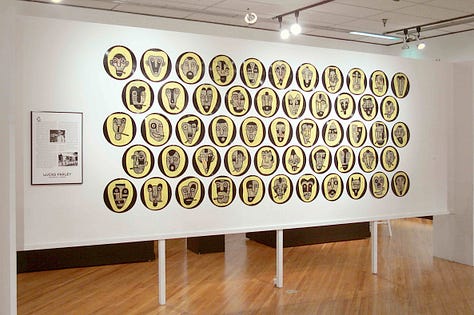

Shortly after returning to his country in 1971, Llort moved to the small agricultural village of La Palma in the northern mountains of El Salvador where he started a workshop which he titled “La Semilla de Dios” (The Seed of God). There he started training local villagers to draw and paint; shortly after that, La Palma started becoming known for the creations that emerged from their workshop. Shortly after the beginning of the Civil War in El Salvador, Llort moved to the capital where he opened a gallery that he named “El Arbol de Dios” (The Tree of God) where he continued exhibiting and selling his work. Over the years, the particular style of compositions that Llort and his artisans in La Palma modeled were adopted by others, to the point that they became a national folk art form. Today, when one searches for Salvadoran folk art online, there are endless examples of this type of objects sold by both online and physical stores— often with no specific attribution to Llort, but unmistakably reproducing the formal elements, colors and overall style that Llort once spearheaded. “He did plant the seed”, Morán says, referencing the name of Llort’s original workshop.

One of the topics that have always fascinated me throughout the years are the processes by which the iconography of a nation is generated. When the nations of the Americas gained their independence from Europe in the 19th century, artists were commissioned to compose the national anthems and design the flags and coats of arms of their newly created nations. Artists were given the unusual job of producing a cultural symbol that would help identify and differentiate the new nation from others by drawing from their collective local heritage and history, which, once officially adopted, would then become etched in stone forever (and so we still sing national anthems of our respective countries with 19th century lyrics that might feel a bit outdated and even absurd, but we still sing them anyway out of patriotic duty).

An unofficial version of those key national identifiers is, of course, a country’s popular art. We think of folk art as synonym of tradition, often without knowing the particular history of what made it become what it is. The general assumption is that a folk art object is the expression of an artistic activity transmitted over many generations and sometimes even connected to ancestral knowledge as part of a long, uninterrupted history. However, the reality is often more complicated.

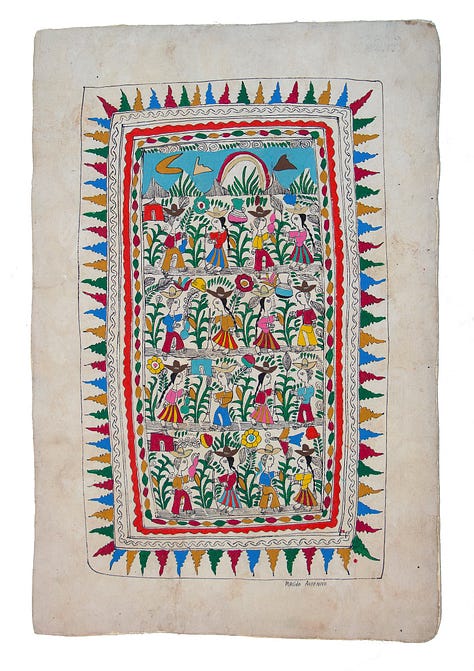

An example in this regard is the tradition of the paintings on amate paper in Mexico— a traditional bark paper that has been made since the pre-Columbian era. The scholar Citlalli Lopez Binnquist, who published a dissertation on the history of amate paper production in Mexico, has studied the process by which amate went from having a ritual purpose in its origins to later become of interest as a sellable craft. Amate was used during the Aztec Empire for communications and to create codices, but after the arrival of the Spanish the production of Amate was mostly banned. Only in small and remote regions, such as Veracruz and the Central Mexican Plateau region in Puebla inhabited by the Otomí people (ñahñus), the production of this paper continued, mostly for ritual purposes up to the modern era. The shift in amate paper becoming a popular craft occurs sometime in the 1960s. According to Lopez Binnquist when I inquired about this with her, “it is interesting to recognize how from different spaces and social groups there is an interest in experimenting with diverse aesthetics, revaluing popular culture and opening new niches for the market.” She continues: “The painting in Amate paper is a combination of the ñahñus of San Pablito [Puebla region] and the nahuas established near the Río Balsas, who had produced pottery ever since pre-Columbian times. They would decorate these pieces with elements of nature, which later were translated onto amate paper. Over the years the designs have been modified and diversified; most recently the ñahñus have also initiated the painting on paper with their own designs.” The creation in 1974 of FONART in Mexico (Fondo Nacional para el Fomento a las Artesanías, or National Endowment for the Promotion of Crafts) helped create financial incentives to promote the production of these crafts primarily for tourist consumption, which in turn stimulated the production of painting on amate paper that one sees today in tourist shops all over Mexico. Because the materials and composition of these paintings sometimes evoke those of codices, they create a sense of an uninterrupted continuation of a millennial tradition. The fact that its current version is a fairly recent phenomenon is not something that the average tourist or even an art student would know about.

The related instance that I find even more interesting is when the adoption of a style (often through a process of popular viralization) happens in a serendipitous way, often influenced by an even smaller set of factors, including, as the Llort example shows, a single artist.

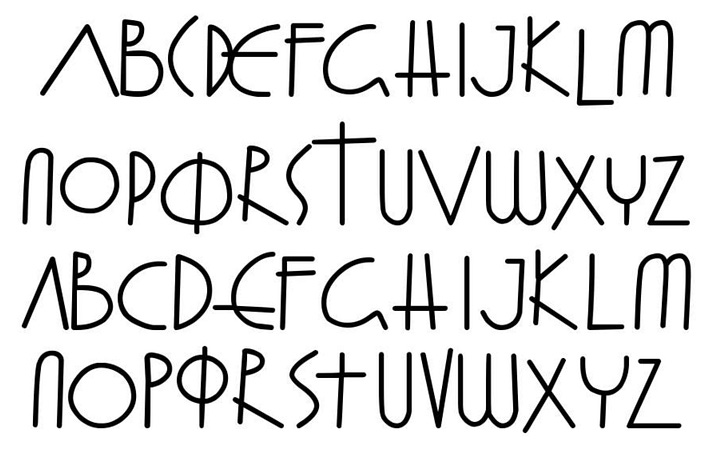

Another example of an artist (also with a theological background) who created a stylistic approach that is not always publicly acknowledged concerns the recently departed Fray Gabriel Chávez de la Mora (1929-2022). Fray Gabriel was a Mexican Benedictine monk, graphic designer and architect who designed many important religious buildings in Mexico starting in the 1950s, such as a redesign of the Cuernavaca Cathedral and the Basílica de Guadalupe in Mexico City in 1976 (in collaboration with Pedro Ramírez Vázquez and José Luis Benlliure). But one of Fray Gabriel’s most enduring legacies is what is known as the Fray Gabriel Font— a primitivist-style typeface resembling a handwritten alphabet that became the standard font of the Catholic church in Mexico for several decades and is still available for free downloads. Like the Llort imagery, the Fray Gabriel font was something that any of us who grew up in Mexico became used to see it used in prayer cards, baptismal and wedding announcements, religious publications, church signage, and more. While typography is not really considered a form of popular art, the Fray Gabriel font entered the collective unconscious just like any other folk art iconography does.

There are great examples of artists who create fictional folk art traditions. One of them is the professional trickster, printmaker and conceptual artist Beauvais Lyons, who as part of his larger project The Hokes Archives created an entire collection of outsider art that he titled The George and Helen Spelvin Folk Art Collection. For this project, Lyons produced a whole series of fictional outsider artists along with their biographies and their oeuvre ranging from paintings and ceramics to dolls and works on paper. Lyons’ work, expertly crafted and humorous, is part of some of the best postmodern art examples of context appropriation and the inevitable reflection that such appropriation inspires.

The case of Llort, however, is precisely the reverse: instead of an ironic appropriation by an artist of an artistic tradition, here the artist creates earnest works that inspire a collective appropriation which in turn results in a recognized artistic tradition that comes to define a national style. While the former aspires to deceive, the latter has no such aspirations, yet sometimes produces the unintended effect of it being (as I once thought it was, in the case of Llort) the result of a long collective narrative and not a whole style generated by a single individual.

I didn’t seek to tell the story of Llort in order to insinuate that we overly romanticize the notion of collective wisdom (even though we sometimes do). I merely wanted to point out that that which often becomes the “canonical folk art tradition” (for lack of a better term) can follow a capricious path, and even while a single individual might happen to trigger a whole movement, as Lewis Hyde once pointed out in his book Common as Air: “All that we make and do is shaped by the communities and traditions that contain us, not to mention by money, power, politics, and luck. And even should the artist or scientist think she has extracted herself from the world to stand alone in the studio, a tremendous array of faculties and mind-states may well attend her creativity.”

This is part of the mystery of how cultural virality works. We are surrounded every day by artistic messages produced by countless creators. The fact that some catch on and others do not may speak more about the community that adopts them than of the individual who initially, say, wrote a particular melody, said a phrase, or drew a bird with big eyes. It is a revealing thread that starts with that small gesture that then becomes widespread, imitated, adopted, famous, standard, and then, finally, tradition. And in an interesting way, the fact that an artist’s creation may be embraced so strongly by the collective so that it eventually dilutes its individual authorship is less an act of possession than a testament of how the one is able to give a voice to the many.

With thanks to José Rodríguez, Ronald Morán, and Citlalli Lopez Binnquist.