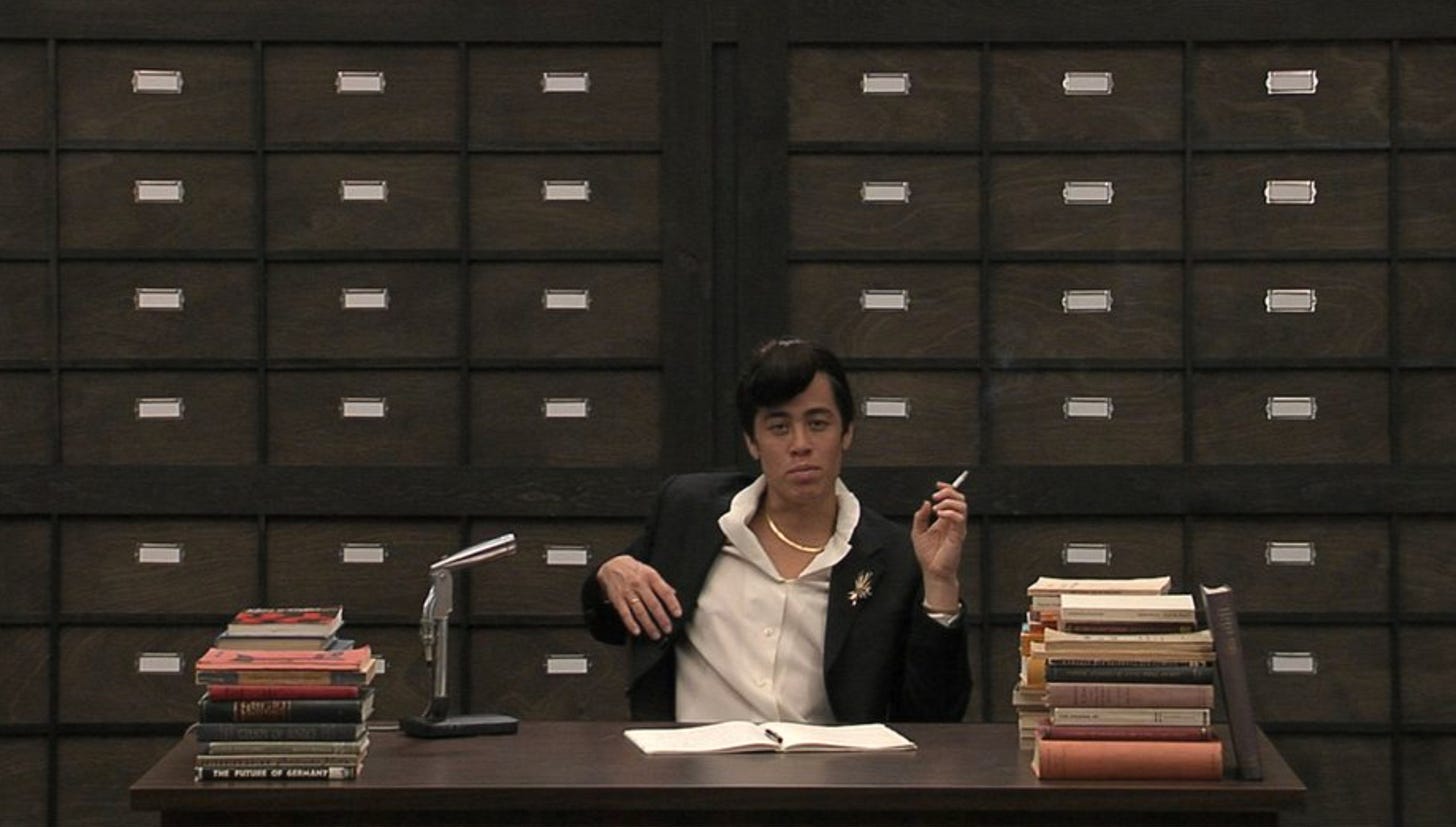

Andrea Geyer, video still from Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, 2009. Six-channel video installation, HD, color, sound, 42 min. Performer: Wu Tsang. Courtesy of the artist.

One of the defining aspects of criminal or civil trials is the goal of arriving at an unambiguous result (guilty or not guilty) through a structured, impartial process. This aim makes language extremely important: the way in which events and actions are defined, the way that evidence is presented, the manner in which legal terms are applied. It is a process in which clarity is essential. In contrast the art practice resents being governed by language: it always seeks to escape definitions, it rebels against the push toward fixed readings— and in fact it thrives in that rebellion, flourishing, —paraphrasing Sontag— against interpretation.

Which is why it is particularly interesting to look at the work of contemporary artists who look at the criminal justice process through their work. The juxtaposition of the accuracy and thoroughness of the legal language when contrasted with the framing within the artistic discourse, often results in works that have great documentary richness while at the same time open a more open-ended conversation and a reflection about larger topic around social responsibility and justice.

I did not want to write yet another column about Ukraine— and yet the subject is inescapable in almost every conversation we have with one another these days. But without being too specific about the conflict, a recent and salient subject to me in recent days has been the question about the long-term historical perspective that we will have about this period.

There is no question that war crimes are currently being committed in Ukraine. David Scheffer, the first U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, and one of the leading prosecutors in criminal tribunals for the Balkans, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, and Cambodia, in a past interview mentioned: “The thing that is so easy about Ukraine is that we know that the orders are coming from the top Because they are publicly confirmed every day. Vladimir Putin incriminates himself every day, his footprints are all over this war of aggression.” The question is whether and when those who committed whose acts will one day be held accountable. When asked about that, Scheffer said: “International criminal justice is the long game – a trial can take 10 , 25, 30 years— but accountability for future generations and for the historical record is extremely important.” Even if its arch of justice is long, International criminal justice is ultimately designed to meet its purpose, which was once described by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan as “the cause of all humanity.”

Thus, reflecting on the historical record and the way in which art can help us make sense of consequential but rather inscrutable complex legal processes by expanding into what they mean in the larger social and political context, I thought of Criminal Case 40/61:Reverb, a 2009 work by Andrea Geyer based on the historical trial of Adolf Eichmann. I reproduce here the description of the work from the artist’s website for better and more accurate context:

Andrea Geyer, video still from Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, 2009. Six-channel video installation, HD, color, sound, 42 min. Performer: Wu Tsang. Courtesy of the artist.

The trial of Adolf Eichmann took place in Jerusalem between April 11, 1961 and May 31, 1962. Eichmann was indicted with 15 criminal charges, among them war crimes and crimes against humanity, to which Eichmann pleaded: “'In the sense of the indictment - not guilty.” He denied any ideological conviction but insisted that he was only following orders. The trial was followed live for its duration by a huge audience in front of radios and for the very first time in front of televisions. The courtroom became an international stage for the discussion of Eichmann’s responsibility for the Holocaust, for the state of Israel’s public face as a modern democratic nation-state and for the event of the Shoa itself, that had until then not been publicly told.

“Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb“ is based on the transcripts and video documentation as well as other historical documents of the trial, like Hannah Arendt’s book “Eichmann in Jerusalem. A Report on the Banality of Evil.” The six-channel video installation features six characters in an abstracted trial scene: Accused, Defense, Judge, Prosecution, Reporter and Audience. Each character is embodied by the same performer: Wu Ingrid Tsang. The performer re-enacts not so much the historical figures but the traces they left behind. This form of re-enactment raises complex questions addressing responsibility, truth, justice, and the notion of Evil and how they extend forward and backward in time within only one person. Through modes of fictionalization – i.e., selecting, enacting, staging, and configuring historical documents – the work opens a dialectical process between the individual as embodiment of history and an abstraction of the individual as universal. It is neither an illusionistic personification of historical facts and characters and a simple re-enactment of history, nor is it an attempt to challenge the Eichmann’s trial.

I contacted Andrea to ask her a few questions about this work and to revisit some of the questions it raises considering current events.

My first question might seem very superficial, but I think is important for those who is not familiar with this work: what would you say was the main motivation for making Case 40/61: Reverb? You decided to tackle a very famous historical event- one which has been extensively documented, studied, and discussed. What was most important to you about revisiting this episode?

I had just finished a 7-year project titled “Spiral Lands” questioning the role of photography and art in the colonization of North America, with a specific focus on the American Southwest. It was through conversations with the poet Simon Ortiz, with whom I collaborated for part of this project, that made me dig deeper into the motivations that had driven me to look at land and land rights as a new settler to what is called the United States of America. My generation in Germany was educated to reflect the critical role of the bystander during Nazi era Germany, something I had internalized as an important ethical stand. Arriving in the US in the 1990s, I had questioned the matter of course with which I settled and as a young artist started to photograph people and landscapes. My project Spiral Lands was a result of this questioning. After completing it and encouraged by Simon, I decided to revisit some of these questions of responsibility as a member of a specific community which returned me to Hannah Arendt, and then to the 1961 Eichmann trial. There were two things that were specifically interesting to me: The discussion of personal and collective responsibility in the face of a national crime, and Arendt’s question if the faculty of thought could prevent a person from doing evil. It was unpacking questions that I had discussed in my work for nearly a decade by then: What is our relationship to the nation states we hold passports for? What is our role and responsibility to these entities? (I consciously differentiate here between culture and state.) What responsibilities do we as citizens/individuals carry for the actions of a government? These are very important questions, in the early 2000s and of course also now, that are all discussed in the Eichmann trial. And are discussed by Hannah Arendt in her reflections before, during and after her reporting on the trial. (There is of course a whole other conversation to be had on how her thinking changed through her witnessing of the trial, off Eichmann, and the court/the law's response to him.)

Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, gave me the opportunity to reflect on these questions, to see if in reading the transcripts of the proceedings, watching the video documentation of it, and reading Arendt’s writing would open up different ways to engage the end of the Bush administration and the political climate it created.

Andrea Geyer, video still from Criminal Case 40/61: Reverb, 2009. Six-channel video installation, HD, color, sound, 42 min. Courtesy of the artist.

The fact that you are German and chose to directly grapple with the terrible history of the Holocaust in this piece makes me wonder if you might have any advice to Russian artists who, in the future, will also have to grapple themselves with the history of the Russian invasion in Ukraine. Was there any insight or surprising takeaway that you gained from making yourself engage with this history?

I am interested in artists who no matter where or when they are born, carry a responsibility to speak two and from the understanding of place and time that we were raised with and are living within, critically or affirmatively. Artists who reflect on what formed their knowledge, their perspective, their understanding off the present moment and how specific aspects of the past were integral to that formation, artists who put these considerations forward as integral aspect of their work. I always believed that from my own perspective to shy away from the difficult aspects off the history of my community, especially the history of the perpetrator, carries the danger to perpetuate that history through silence: The danger to become a bystander and affirm an unreflected/unprocessed past/present. But again, I don’t see it as my role to advise others, but rather listen to other’s ways of engaging their history (or not) and learn and reflect on that as a way to take account of my own role/responsibility.

.

What, in your view, did the format of the trial offered you as an artist? Was it the theatrical/performative aspect of it? And can you share your thinking behind making the final version of this work as a multi-channel installation?

There are so many levels of performativity in the Eichmann trial. There is the performance of law and the court system in the young state of Israel, there is the performance of creating a record of history through the witness testimony by the prosecutor, and there is the performance of the obedient follower, whose “only fault” it was to follow orders. And last but not least we see the performance of Hannah Arendt as the intellectual reflecting on the proceedings. All aspects of performance in this trial were purposefully and consciously staged by the protagonists. There was use of theatricality but also documentary and narrative strategies in the trial itself. It was a very interesting challenge for me as an artist to work with that, to translate that forward into this moment, reflecting on the different things at stake for everybody involved, thinking through how and why these were important things to think through in the present. The idea that the legitimacy of law legitimizes a state; the importance of historical record making, of really knowing what happened; the question of where responsibility lies when someone follows orders and the question of choice in that; and Arendt’s question: “Could the activity of thinking as such, the habit of examining and reflecting upon whatever happens to come to pass, regardless of specific content and quite independent of results, could this activity be of such a nature that it "conditions" men against evil-doing?”[1] There is a lot there that feels urgently relevant today. The negotiation of these important core questions and the way they were performed, is also what led me to the final form of the piece. The screens surrounding the viewer create the impression of a Kafkaesque archive which is a physical archive or history and imagined archive of the present unconscious. Positioning a viewer in the middle of it and in the middle of the abstracted trial that was translated forward in time, was offering a space of reflection that is both past and present, conscious, and unconscious. The staging of the viewer in the center asks them to turn their body to experience the whole piece. It activates that space and makes it self-reflective as viewers view each other’s becoming performers themselves within the framework of the installation.

[to be continued]

[1] Arendt, Hannah, Thinking and Moral Considerations , Social Research, 38:3 (1971:Autumn) p.417