The Cultural Performance of Louis Shotridge

A real-life curatorial fable.

Louis Shotridge in Tlingit ceremonial costume. Courtesy of the Penn Museum

In recent months the subject of repatriation ( today with the more favored term of rematriation) of indigenous artifacts to their original indigenous communities — a subject long avoided by museums— has gained unprecedented energy. About a month ago, Colgate University announced that it would return more than 1500 ancestral artifacts to the Oneida Indian Nation. Similar steps are being seen in museums throughout the United States, ranging from New Haven to Alabama.

The rematriation movement is taking many forms from public campaigns to even the creation of an indigenous-founded and run restaurant at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of Berkeley that celebrates the traditions of the Ohlone people that at the same time advocates for the sacred objects that remain currently in its collection.

Whenever we discuss the history of the extraction of native American artifacts and sacred objects from their communities there is a particular, tragic and yet somewhat obscure figure that I once wrote about who comes to mind for me: someone whose story embodies the many complexities, ironies and dark legacy of this colonialist practice. He was likely the very first Native American curator on staff in an American museum. His name was Louis Shotridge.

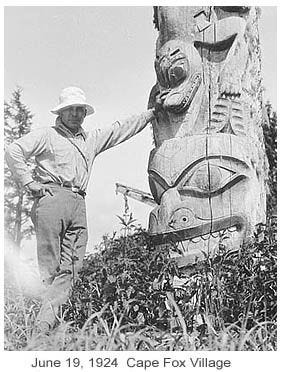

Shotridge (1882–1937) was Tlingit, an indigenous nation from the Pacific Northwest. He was born in Klukwan, Alaska, near the present day city of Haines. From an early age he showed versatility, an ability to move between the traditional world of the Tlingit and the modern culture of the United States, which Alaska had joined as a district in 1867. Some described him as a tall and attractive man with a fine singing voice.

The 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon was the event that launched his career. His wife Florence Dennis, an accomplished weaver of Chilkat baskets, was invited to the exposition to perform a demonstration of her craft, and Shotridge accompanied her with the purpose of selling a few Tlingit artifacts. George Byron Gordon, then curator and eventually director of the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia (today known as the Penn Museum), was one of his customers. The Penn Museum had recently been founded by the Gilded Age families of Philadelphia with the aspirations to rival the British Museum. Gordon was determined to put the museum on the map, and by most assessments he did—quickly building a vast collection and fundraising for an expansion of the building. Gordon became director of the University Museum in 1910, in a key period of expansion of American museums that created a frantic race to collect historical artifacts. Gordon saw in Shotridge a young, energetic, smart, and eager (although inexperienced) conduit to the riches of the Pacific Northwest. Shotridge saw in Gordon a mentor and a bridge to modern American society.

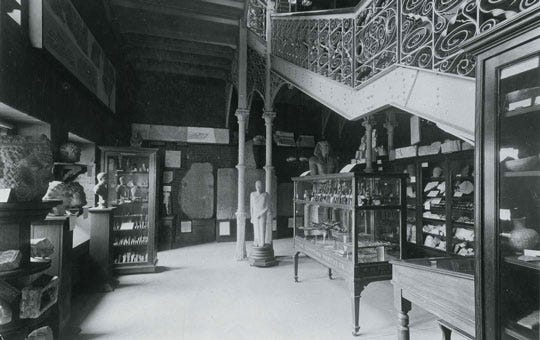

Egyptian and Mediterranean gallery at the Penn Museum in 1898

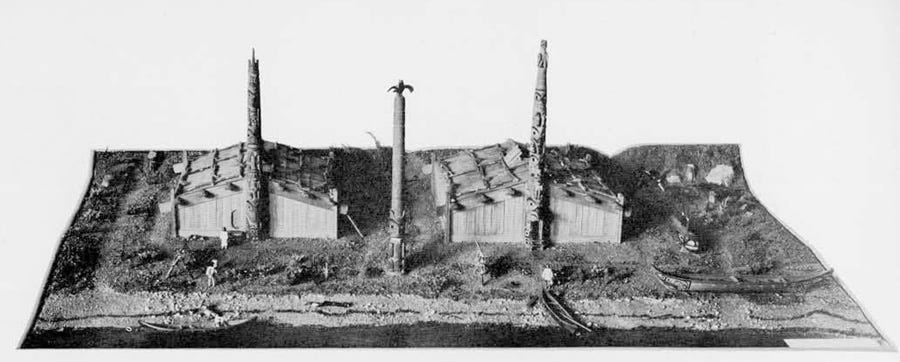

Model of a Haida Indian village constructed by Louis Shotridge, Penn Museum

Shotridge did not have a formal education in ethnology or anthropology; he received three years of training at the University Museum before being made assistant curator there in 1915. In 1912, through the help of anthropologist Frank Speck, he and Dennis met the linguist Edward Sapir, with whom they worked. In 1914 they met Franz Boas, considered the father of modern anthropology. Gordon arranged for Shotridge to attend Boas’s lectures in New York, and as a result Boas worked with Shotridge to develop the first record of Tlingit phonology. Boas’s training was essential to Shotridge, who learned processes of recording and other methods to conduct research that were key in his later work in the museum. He was exacting in his record keeping and correspondence, a quality today’s researchers are grateful for. One of his early assignments, a scale model of the central section of the village of Klukwan, was so painstakingly produced that it continues to be a prized component of the museum’s exhibits.

Shotridge truly believed in the necessity of salvaging and documenting the traditions of his people. In 1923 he wrote, “It is clear that unless someone go[es] to work [to] record our history in the English language and place these old things as evidence, the noble idea of our forefathers shall be entirely lost.” Over the course of his career, Shotridge collected more than five hundred items for the University Museum. While not astronomical in quantity, the quality of the objects he obtained is extraordinary and they constitute one of the great collections in the world of such material. Shotridge had a unique advantage over competing collectors; being a native speaker of Tlingit, familiar with local cultural codes and the region in general he knew where to look for valuable items and was likely more trusted by their owners.

Shotridge’s detractors usually zero in on one particular issue: his attempted (but ultimately failed) acquisition of the spectacular Klukwan Whale House collection. Shotridge had always been keen to obtain this collection—an ornate house screen and various posts—for the museum, but the community was reluctant to let it go. In 1922 he lobbied for its acquisition, offering $3,500 to the community, but the offer was rejected. Shotridge had a direct familiar connection with this house, as his father, Yeilgooxú, had been its headman. After Yeilgooxú’s death, the community had decided that the title should be passed to the headman of the Raven House instead of the customary heir, Shotridge’s uncle, who was considered unfit. Shotridge convinced his uncle to contest the headmanship of the house and using American laws he laid claim to the property as the son of Yeilgooxú. The community was profoundly divided over the issue. Shotridge was aware of the havoc he was causing, but that did not deter him from making another attempt at taking the house posts and screens in July 1923, an attempt that also failed. In the end he gave up, expressing regret later for this episode of his life, but the controversy continues to haunt his legacy.

Shotridge appeared to be extremely eager to satisfy the demands of Gordon and the museum in obtaining objects and performing—symbolically and literally—the role of native interpreter for institutional and pedagogical purposes. Shotridge and Dennis became living interpreters of Native American customs in general, not just those of the Pacific Northwest. In one of the most frequently reproduced photographs of the couple, they are wearing outfits that appear more appropriate for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show than Alaska. Of their reenactments, ethnologist Elizabeth P. Seaton has written, “What is striking about these public performances are their acts of miming alterity. Playing to others’ expectations as to what constitutes Indianness, the Shotridges are held to enact Anglo-American desires for a pure, unsullied order of origin in a world which has come undone. In this respect, the two (in) authentic Indians are posed against the degenerate hybridities of an industrialized modernity.”

The historical judgment against Shotridge has been harsh, perhaps rightly so. But the extent to which Shotridge was an “(in)authentic” performer or an instrument to satisfy expectations for whites about “the other” might feel debatable to some— especially if coming from someone who is not indigenous. Shotridge’s historical role of the colonial translator is fairly common in the Americas, the most important example being La Malinche, a much reviled character who feminist theorists and writers later sought to reevaluate and reify, emphasizing the given sociocultural and psychological forces that she was subjected to and unable to contest as a colonized indigenous woman.

Through his contemporaneous writings and recorded activities we can form an image of how Shotridge negotiated his own fractured identity and how he helped others articulate the negotiation between cultures. He considered it important to integrate native and colonial culture so both sides could get to know each other. He particularly wanted those who shared his native heritage to have the opportunity to integrate into what he described as “the progressive world” of United States collective culture. It was that “progressive world” that drove him to extract more and more material from his people, and he found himself maintaining a social standing in one world through what he could obtain from the other.

Shotridge’s last decade of life was probably his darkest. When Gordon died in 1927, Shotridge lost his main supporter at the museum and a friend of many years. Shortly after, in 1928, his second wife, Elizabeth Cook, died of tuberculosis. (Margaret Dennis had also died of tuberculosis, in 1917). Shotridge spent a good deal of his savings taking care of his wife and providing for their three children. The Great Depression affected the ability of the city of Philadelphia to make its annual appropriations to the museum, and in 1931 Shotridge’s pay was cut by fifteen percent and in 1932 was eliminated altogether. Shotridge, in his fifties, went back to Alaska, cut off from the south, unable to do the only job he had been trained to do. In 1935 he took the job of fishing guard in Sitka—a government position that locals resented, as he was in charge of preventing the illegal fishing that many there saw as vital to their sustenance. It was there that Shotridge met his end, a death that has been the subject of much controversy. He was found on the ground in Redoubt Bay, where he had been lying for several days, injured. He was taken to a hospital in Sitka where he died of a broken neck. According to the official story, his death was the result of an accidental fall. Others theorized that a poacher Shotridge had recently ordered off the river had taken revenge, and there were rumors that other enemies—or the spirits—had sought retribution for his extracting of sacred objects from his people. What is certain is that Louis Shotridge, the first Pacific Northwest Indian to ever work in a museum, the first recorder of Tlingit grammar, the ethnographer, performer, translator, and traveler, died as an unwelcome member of his own community, destitute and largely forgotten.

Shotridge’s writings display a sincere concern for the preservation of culture. There is a sense of urgency in his reports, as if he knew that the pace of modernity was quickly wiping out the world he had come from. His attempts at mediation, such as the promotion of oral history, might have been self-serving, but they feel authentic. There was narcissism in his enterprises, his boisterous and even arrogant claims that only he could find the treasures that would salvage the culture of his people. At the same time his letters also reveal someone torn and conflicted about his constant negotiation between cultures, a yearning for acceptance.

In order to better understand the story Shotridge left behind to those closest to him, I contacted his family members. One of them was Israel Shotridge, an artist and grandnephew of Louis Shotridge. In 2009, Israel and his wife, Sue, were in New York for an exhibition at the Museum of the American Indian, where Israel was exhibiting some of his celebrated traditional carvings. I took them out for a drink. “I was fixated by Louis, even before I knew he was my uncle,” Israel said. He had discovered that he was related to Shotridge only when he was in college. Of his relatives, Israel is the only one who has taken the last name Shotridge, causing some tensions among the family (they all have kept the Jackson last name), and the legacy of the granduncle still generates mixed reactions. Israel, in contrast, has chosen to embrace it. “Shotridge” is an anglicized Tlingit version of Shaadaxhícht, the name of Louis’s maternal grandfather. “You know, the government, they try to erase your name, your history, history that you and I should know about,” Israel said.

I asked him if the rumors about foul play in Louis’s death were true.

“If you lived in Alaska, you would know,” he said, smiling, and took a sip of his beer.

(this text is a summarized version of one of the chapters of my 2010 book “What in the World”).

Súper interesting as always!