In 1992, as an art student, I had the privilege of attending a lecture and reading by John Cage at the Rubloff Auditorium of the Art Institute of Chicago— a celebration of his 80th birthday and one of the last public events he ever participated in before his passing five months later that year. At the end of the program there was a Q&A session. When that portion of the program was introduced, Cage, with his typical humor, said: “You may ask me any questions. I can’t promise I will know the answers, but I can certainly respond to them.”

One of the first things one learns an art museum educator is that there are never any final answers when it comes to interpretation: that is, beyond hard data about an art work (dates, materials, and other specific contextual information) no one can ever provide an “answer” about what something means— a fact that is often confounding to the art novice.

So this idea of responding without a definitive answer (but provocatively pretending I had one) was in the back of my mind back in 2010 when I launched The Estheticist, an art advice column directly (and surreptitiously but also playfully and shamelessly) inspired in Randy Cohen’s New York Times Magazine Sunday column The Ethicist. The Ethicist, which is still published today with other contributors, is an advice column that helps people deal with a whole range of ethical dilemmas (“my friend won’t leave her abusive husband- what should I do?”; “Is it OK to let my relatives believe my dead sister is still alive?”, and so forth). Dannielle and I would read to each other the inquiries every weekend, and then after discussing the problem and guessing the answer would read the Ethicist’s response.

I thought it would be interesting to pursue a similar approach for the art world, since as we all know we are an incredibly secretive community where there are few if any public outlets to air our professional conflicts, woes and ethical quandaries. Presenting them in public can often result in a career-ending move and reveal feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt that can only diminish the art world’s opinion of someone.

The Estheticist is an art project, of course— playing with the ridiculous fiction that I am an ethics expert (which I decidedly am not) and that I have all the answers (which I definitely do not have). Regardless, I received many letters and I spent several months answering them. Each question was an opportunity, I felt, to examine a sociological problem in the art world (which is one of my passions) and try to lay out its components in order to understand it better. The range of inquiries included many requests for basic art career advice (“how do I get a gallery?”) which I found of little interest, but also many others that outlined specific problems that I felt were worth taking on (e.g. “I broke up with my partner and we are no longer on speaking terms: how to handle the copyright of our collective works?”).

I often had to turn to experts on areas that were beyond my paygrade to generate a proper response, which was weird and interesting. In the case of one question, “what if the Renaissance had not happened?” I turned to an art historian colleague who is an authority on the period, and he sounded offended. “What a stupid question!” he told me, and refused to engage any further with it. My goal, as I unsuccessfully tried to convince him to talk to me, is that I wanted to embrace even the dumbest questions as I felt that they offered potential thought experiments and perspectives that were worth reflecting on and could shed light on interesting problems (for instance, regarding the Renaissance question, I felt there’s a philosophical problem about the cause-effect of art practices and the linearity of canonical narratives, as well as the question of how one can do art criticism about an art period without the theoretical framework and references from prior periods). Which is to say that, in the end, The Estheticist ultimately is not about providing answers, but about expanding questions.

So I felt it was appropriate to revive this exercise and every now and then open this space for possible questions. I present a few inquiries from past years below. I welcome your own questions, which will be considered for inclusion in future columns of Beautiful Eccentrics: The Estheticist. (All questions will be treated as anonymous unless the author requests their name to be used.)

How can a curator answer every single email to every single artist who drops an email to her/his inbox? Is it ok not to answer?

Istanbul curator

I am reminded of the brief and entertaining period when Arthur Danto joined Facebook, shortly before his passing (granted that he was not a curator, but a philosopher and critic, yet the story still has a useful morale). As most individuals of his generation, Danto did not seem too familiar with the dynamics of social media, and he tried to treat it instead like old fashioned correspondence. He was delightful and dedicated, and for every little comment he received he would try to write a substantial response. I suppose he eventually realized this was impossible to do, given his massive following and the number of inquiries he must have received on a daily basis: it was a full-time job. Shortly after his foray into that site, he quietly vanished from it (and we sadly lost him shortly after).

That story aside, it is part of the curatorial profession to engage with artists professionally and respectfully and learn to balance respectful acknowledgment with the setting of limits. Artists have to be considerate, especially with curators who have high visibility and undoubtedly receive countless solicitations and requests. As for curators, to altogether ignore an artist’s legitimate inquiry via email might be seen as a sign of arrogance and disrespect. Best practice, if unable to answer each email individually, is to have a series of readymade responses, such as, “thank you for making me aware of this material, I will take a look at it but as you may know I receive many requests every day and may not be able to give you a full response.” In the case however, of artists who constantly bombard you with requests and announcements and do not appear to show any prudence in their communications nor respect of your time, curators are not required nor expected to reciprocate.

As artists we have the privilege of offering our colleagues artworks in exchange. Are there any unspoken rules about artists bartering pieces?

Anonymous Artist, Mexico City

Exchanging pieces amongst artist colleagues is a wonderful practice. To propose an exchange, however, has to be done carefully and with tact. For an artist to propose a trade with one who comparatively is more established and/or whose works have a greater market it would be presumptuous and would place the more successful artist in an uncomfortable situation.

I advise to proceed with caution when suggesting a trade. Artists at the same level can certainly and freely propose trades to each other, but the interest in each other’s works must be clearly mutual as well as the recognition that both are at the same level (which is actually hard to do as most artists have a slightly more aggrandized vision of where they are placed reputation-wise in relation to others). A unique case was Sol Lewitt, who would routinely exchange works with less well-known artists without consideration of the monetary discrepancy of the exchange — as Lewitt did not think of that art work in terms of it being a commodity— but again it is the choice of the established artist to pursue this exchange.

The best opportunity to propose a trade most typically emerges when an artist that one admires expresses a lot of interest for a particular work of yours; it is then perfectly reasonable to suggest a trade. One should not be picky either: to demand a particular work from the collection of that artist would tarnish the exchange.

What do you do when you realize that you are being been stalked, used and vampirized by a so-called friend, someone much younger than you? How do you let the world know that you reject this person? I confronted my friend but he reacted surprised, as if I was mad. I feel as if I was in the “All about Eve’ movie, surrounded by pathological narcissists on coke. I want to escape! Help, please!

Best,

Don Quixote, Spain

I gather that by being “vampirized” and “stalked” you are referring to a colleague who has taken advantage of your friendship, perhaps plagiarizing your works or using your friendship for advancing their personal career. The fact that they sound like drug-addicts is not promising either.

Whatever is the case, it appears that you have surrounded yourself with people that are detrimental to your well-being and your creativity. It is very important for you to keep in mind that these so-called “friends” don’t represent the totality of the art world: there are people out there that will value and support you as a friend and as artist. Your job is to find them, thus creating a better environment for yourself. Whether that means to simply cutting all ties with your stalker, or to move to another neighborhood, town, or country, is something that only you can decide. But this decision will likely require that you change your life as it is, expanding your professional circles of friends and acquaintances, seek out the individuals you admire, and build a group of people who share your same values. Usually we blame the others for our own inability to change our situation, but as you yourself suggest this situation has now become untenable and you are the only one who can change it.

Your focus should be to make art, not in worrying about people around you. This focus will ultimately be rewarded.

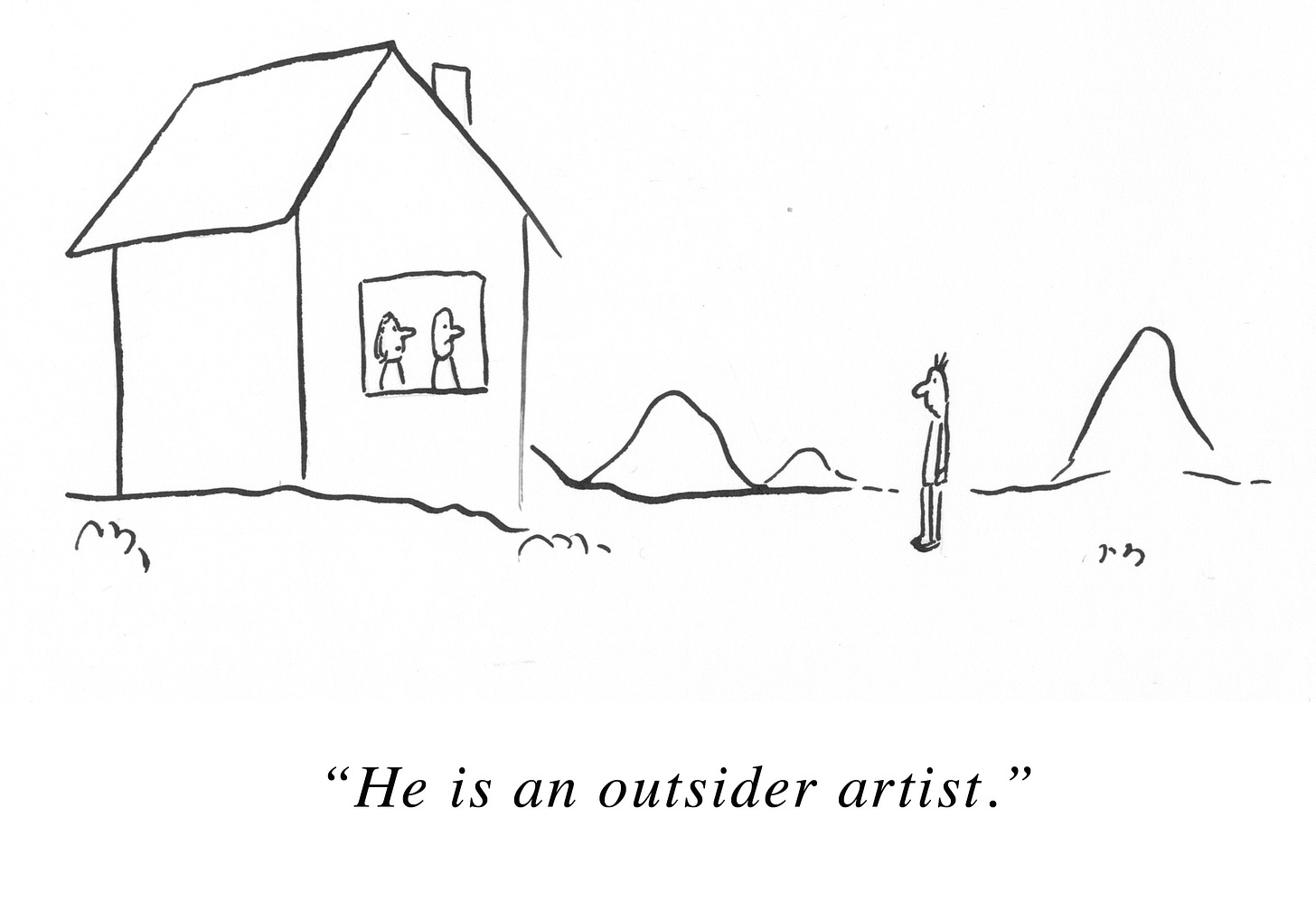

My work is about challenging the system of art, but how can I engage the art world if to engage with it is essentially against my rules? Either I stay isolated forever or lose the integrity of my practice.

Sincerely,

Outsider, California

My suspicion is that you never really wanted to be outside in the first place. If you are so concerned by the acknowledgement of the art world for the kind of work that you do, most likely you regarded your supposed rebellion against art as some kind of vacation from the system, but always with the hopes that they system will come back to embrace you — in other words, you want to have your cake and eat it too. It may be better for you to come to terms to that fact and think about how you can still challenge the system by still being engaged within it. If, on the contrary, you find that your philosophical stance really takes you outside of it, you will not miss it much.

Dear Estheticist,

How many viewers are enough?

Paul Ramirez Jonas

They will never appear to be enough. But you will know they are too many when you lose sight of yourself.

Just as a brief postscript to this piece: at that 1992 Cage event I remember him reading some of his mesostics (a poetic form he was ready committed to) , some dedicated to Erik Satie, who was a big inspiration to him ( and a true eccentric, in fact the very source of the title of this column as the author of the work La Belle Excentrique). While I lined up to get his autograph at the end of the talk, a young woman in front of me —likely an art student— asked Cage to draw her a cat. It was hilarious. Cage looked at her like in a combination of disbelief and amusement, and then did draw her a cat. I wish I had come up with such an original request.